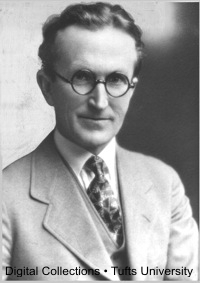

Bruce Wallace Brotherston (August 12, 1877-April 17, 1947) was a Universalist minister, author, and educator. After 16 years in the ministry he went on to teach philosophy, religious education, and philosophy of religion at St. Lawrence University and Tufts College for twenty-one more years.

He was born at Cobourg, Ontario, Canada, to Glorianna “Lena” (Hendry) and James Brotherston, a ship captain who traveled widely, circumnavigating the world four times. The ninth of eleven children, his parents emigrated to Canada in 1867 from Glasgow, Scotland. He was brought up in “a Christian home” and “a Christian church” whose theology was Calvinism. His grandfather, Peter Brotherston was a minister at Alloa, Scotland while his brother Arthur, two years older, graduated from Bangor Theological Seminary and entered the Congregational ministry. A sister Lena Stirling Brotherston, two years younger, was a Presbyterian missionary in India, 1908-1918.

Brotherston’s early education was at Cobourg’s public secondary school, the Collegiate Institute. When his parents relocated to North Adams, Massachusetts he completed his studies at Drury Academy, its free public high school. He earned money during high school and college as a tinsmith. While a student at Williams College, he also served as president of the local Sheet-mental Workers’ Union for a year. Later during his years as a minister, he re-roofed one of the churches where he preached.

Graduating with an A.B. from Williams in 1903, he entered Andover Theological Seminary to train for the Congregational ministry, a natural choice since the church and Christianity had been his catechism since childhood. It bred in him he said “the inestimable value of the individual, the social nature of man, and the kinship. . . of man with nature.” Reflecting on this period, years later, he felt fortunate that his studies at Williams – Carlyle and Emerson coupled with classes in science – “drove” the determinism of Calvinism from his mind and gave him the “freedom of the spirit” to become a minister.

Brotherston graduated from Andover with an S.T.B. in 1906 and spent the next year there as a teaching fellow. In 1907 he married Jessie May Bowen; their union produced two sons. Later that year he was ordained to the Congregational ministry. His pastorates included North Conway and Intervale, New Hampshire, 1907-12; Gilbertsville, Massachusetts, 1913-21; and Milton, Massachusetts, 1921-23.

When his preaching, which stressed religious liberalism and the social gospel, led to increased friction with conservative congregations, Brotherston returned to school, studying philosophy at Harvard Divinity School, 1912-13, as an Andover Fellow. He continued his studies at Harvard’s Graduate School during his next two settlements and was granted a Ph. D. in 1923. His thesis was on “Moral evil and the social conscience.’

Finishing his doctorate, Brotherston applied for and was accepted into fellowship with the Universalist General Convention. In 1923 he was appointed Moore Professor of Religious Education and Christian Ethics at the Universalist Theological School of St. Lawrence University, in Canton, New York. In 1928 he was appointed Professor of Philosophy and Head of the Department of Philosophy for the university’s College of Arts and Sciences.

One of Brotherston’s strengths as a parish minister was his commitment to the religious education of young people. He taught religious education to theological students in the university classroom, supervised the religious education program at the local Canton Universalist Church, and served on the Universalist Board of Religious Education. Combining hands-on practice with classroom theory about religious education allowed theology students to earn certification as Directors of Religious Education.

In 1930 Brotherston moved to Tufts College in Medford, Massachusetts. At Tufts, another institution founded by Universalist’s, he was appointed Fletcher Professor of Philosophy, chair of the Philosophy department, and Professor of Religion in the School of Religion.

One of his students at Tufts, Carl Seaburg, said that he “lectured with dry voice and desiccated manner, his fingertips lightly touching as he articulated his philosophy of liberal religion.” George Burch, his successor at Tufts, wrote that he was “humble, infinitely patient, and devoted to his students,” and “in turn was respected and loved by them. His sense of humor and fund of stories enlivened his lecture, but his technical language made them difficult for the less rigorous minds. James and Dewey were outstanding influences on his thinking. He was a pragmatist in philosophy and a liberal in religion.”

Brotherston’s book A Philosophy of Liberalism, 1934, was published by Beacon Press. It described a belief system based on “faith in an inward and nature-made directive principle in mind, directing human nature toward social unity, and even beyond humanity to the metaphysical satisfaction of a religious urge.” Professor James Seelye Bixler of Harvard Divinity School in The Christian Register added that Brotherston felt that “innate tendencies are at work in man and in society which need only to be explored and developed to be turned to the highest moral account.” That way, “the good can be made to prevail.”

The Christian Leader in its review concluded that “this is a book to read slowly and ponder” for “it is a very sincere, penetrating, and comprehensive study of the most searching questions before our time.” Harold Speight, the reviewer, then asked, “Can our confidence in intelligent, socially-minded effort be shown to rest on any basic reality in human nature and in the world-order? It is a courageous thing even to attempt the formulation of an answer.”

When William E. Hammond examined Brotherston’s answer in The Christian Century, he asked “Does [it] offer an adequate philosophy for liberalism? This reviewer is sufficiently convinced of its merits to urge for it the widest publicity, not only among professed liberal but among all classes of thinkers and religious leaders.”

Brotherston regularly contributed articles on epistemology, social behaviorism, empiricism, and ethics to scholarly journals including The Journal of Religion, The Monist, The Open Court, The International Journal of Ethics, and The Journal of Philosophy. His 1939 essay “What Christianity Means to Me” was included in Tufts Papers on Religion edited by Clarence Russell Skinner and published by the Universalist Publishing House. He was a member of the American Philosophical Society and the American Association of University professors.

Death

When he retired in 1944, Tufts appointed him Fletcher Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus. He and Jessie moved to Holliston, Massachusetts where he did some farming, grew greenhouse flowers commercially, and continued to write. He died in his sleep in his seventieth year. Friend and colleague Alfred Storer Cole and former student assistant Leon Fay conducted a funeral service at Goddard Chapel, Tufts College.

Sources

The Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School, holds his Universalist ministerial file. For further biographical data see George B. Burch, “Bruce Wallace Brotherston,” in Philosophical Review (1949); Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers (2005); and Who’s Who in Philosophy (1952). Other sources include Louis H. Pink and Rutherford E. Delmage, editors, Candle in the Wilderness: A Centennial History of the St. Lawrence University 1856-1956 (1957); an unpublished manuscript at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library by Albert F. Zeigler, “Bruce Brotherston, John Calvin and Hosea Ballou”; Robert F. Halfyard Family Group Record for Captain James Brotherston (2009)and A Dictionary of North American Authors Deceased Before 1950 (1951). There is an obituary and editorial in The Christian Leader, May 3, 1947; and obituaries in the New York Times and Boston Herald, April 18, 1947.

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted February 26, 2011