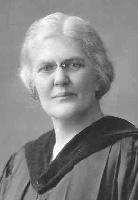

Florence Buck (July 19, 1860-October 12, 1925) was a Unitarian minister at a time when women ministers were uncommon and a leader in the development of Unitarian religious education. She served as Associate Secretary of the Department of Religious Education of the American Unitarian Association and was editor and author of significant religious study materials.

Florence was born in Kalamazoo County, Michigan. Her parents, Samuel P. and Lucy Reasoner Buck, raised her as a Methodist. After studying at the Baptist College in Kalamazoo she was a science teacher at Kalamazoo High School. She became head of the science department and eventually principal.

In 1890 Buck attended services at the Unitarian church in Kalamazoo, where Caroline Bartlett and Marion Murdoch were ministers. Buck was drawn both to the liberal theology of the church and to Murdoch. Their friendship developed into a devoted partnership that lasted the rest of Buck’s life. In the summer of 1890 Murdoch and Buck attended the Sunday School Institute in the Chicago area. They traveled together, stopping in Humboldt, Iowa where Murdoch had formerly been pastor.

Within a year Buck, already preaching sermons and performing “ministerial duties,” had resigned from her teaching post to pursue ordained ministry. Murdoch negotiated with influential colleague Jenkin Lloyd Jones to secure half rates for Buck to attend Meadville Theological School. Buck was ordained at All Souls Church in Chicago during the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions. Eight women ministers, including Antoinette Brown Blackwell, attended the ordination service. Murdoch did post-graduate work while Buck attended Meadville and they studied together for a year at Manchester College in Oxford, England. Following graduation, Buck and Murdoch were co-ministers at Unity Church (First Unitarian) in Cleveland, Ohio, 1894-1900.

After travel and study in Italy and Germany, Buck held a field work position, reviving a church in Mount Pleasant, Michigan, then briefly serving a church in Manistee, Michigan. She was minister of the Unitarian church in Kenosha, Wisconsin, 1901-10. Her partner Murdoch served a congregation in Geneva, Illinois, just over the state line. Murdoch retired from Geneva in 1906 for health reasons. Hoping for a healthier climate, in 1910 Murdoch and Buck moved together to California, where Buck served in churches in Palo Alto, 1910, and Alameda, 1911-12.

Having come to the ministry from teaching, Buck early expressed an interest in religious education. Current liberal theology strongly influenced the educational work of her ministry. Taking all aspects of life as religious material, she welcomed insights from science and scholarship and encouraged people to find divine inspiration from their hearts and souls. In a sermon given in Cleveland, The Divineness of Common Things, she taught that “the commonplaces of life, the things which are near and familiar, have lessons to teach us, have revelations of God to make to human hearts.” She cautioned that science is no threat to God’s revelation in nature; rather, nature invites communion with God. Scripture teaches that “the place on which we stand is holy ground.” She declared that the full meaning of those words would be best understood when “we listen to the present revelation of God all about us.”

Also reflected in Buck’s ministry is the impact of the Social Gospel movement, calling for the creation of the Kingdom of God on earth through cultivation of good character, moral development and social reform. While in Cleveland she and Murdoch established two kindergartens, one in the church and one in a poorer section of town. They also preached about the Salvation Army and the settlement movement. In Kenosha Buck called the public’s attention to the needs of youth and founded the Kenosha Playgrounds Association.

While in Cleveland Buck and Murdoch developed an outline for Bible Study which they published in the Iowa monthly paper, Old and New. Buck was often called upon to speak at the annual gathering of the Western Unitarian Conference and the Western Unitarian Sunday-School Society. In 1894 she gave a presentation on “Pictures as Lesson Helps” demonstrating her interest in making religious education more appealing to young children. In 1897 she spoke on the topic “New Features in Sunday School Work.”

Buck was influenced by Jenkin Lloyd Jones, a pioneer in developing new methods to engage children in a discovery process of education. She and other women ministers of the West were followers of the child development theories advanced by G. Stanley Hall. They often based their kindergarten classes on his models. Buck also studied the early writings of John Dewey.

In Cleveland and Manistee Buck organized Woman’s Alliances and joined other women’s groups as well. She was a member of the Kenosha Women’s Club during her ministry there. While in Kenosha she spoke frequently in public about the value of women in society and the need for women to assume leadership roles. When she moved to California she frequently promoted women’s suffrage. Because of the crusade for suffrage Buck and her female colleagues had tenuous and often tense relationships with those at denominational headquarters in Boston.

Despite her gender and her location in the West, Buck’s leadership skills were noticed by those in Unitarian headquarters in Boston. When the position of Associate Secretary of the Department of Religious Education became available at the AUA, she was recommended as the only candidate. In this position from 1912-25, Buck edited The Beacon, a newsletter for children, wrote for the Christian Register, edited the Beacon Course of textbooks and the Beacon Hymnal, 1919. She was the author of the textbook, The Story of Jesus, 1917, and three bulletins put out by the Department of Religious Education.

The move to Boston shifted Buck towards the center of the Unitarian movement, to the detriment of older bonds with leaders in the West. Although there is no evidence that she continued her suffrage activity after this move, she used The Beacon to encourage girls to develop their full potential. She developed a close working relationship with the Executive Secretary of the Department of Religious Education, William Lawrance. All of their writings on religious education are in harmony, and they often reference one another in their work. Buck ran a special profile on Lawrance in The Beacon, and Lawrance later wrote a laudatory obituary of Buck for the Christian Register.

In The Beacon Buck directed appeals for service and monetary contributions to children, teachers and parents. Recipients of the funds included Unitarians in the Khasi Hills, students studying at the Brahmo-Somaj school in India, Belgian Hunger Relief, starving orphan children in Armenia, the Chinese Famine Fund and French Orphans. She praised all efforts at helpfulness and service, but emphasized international relief. She also used the paper to promote World’s Temperance Sunday and the Unitarian Temperance Society essay contest.

Buck promoted the use of hand-work and pageantry in Sunday School classes and pioneered in the use of dramatics in education. Strongly influenced by specialists in the psychology of religious education, she urged teachers to take a developmental view of children when planning curricula. The introduction to each volume in the age-level-graded Beacon Course includes a description of the developmental needs and characteristics of the child.

In addition to her writing and editing, Buck had a large public teaching role. The Department of Religious Education held two summer institutes for teacher training every year, and Buck repeatedly served on the institute faculty. In 1922 and 1923 she organized and led three Pacific Coast teacher training institutes that attracted clergy from other denominations in addition to Unitarians. She also traveled and consulted widely with Sunday Schools and preached at numerous churches. She represented the American Unitarian Association (AUA) at Religious Education Association (REA) meetings and in 1917 was elected to the REA Council, becoming vice-chairman of the REA Department of Church Schools.

Meadville Theological School conferred an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree on Buck in 1920. She was the first woman to receive this honor. In 1923 she was the first woman to preach at King’s Chapel in Boston. In 1925 she was the first woman to be named Executive Secretary of the AUA Department of Religious Education.

Death

Buck died in Boston of typhoid fever. When the AUA built a new building in 1927, one of the rooms was named the Florence Buck Memorial Room. Funds for furnishing the room came from those who loved her, including many children, as a “tribute of respect and affection.”

Sources

There is a Florence Buck file in the archives of the Unitarian Universalist Association in Boston, Massachusetts. Letters of Florence Buck and Marion Murdoch to Jenkin Lloyd Jones and papers relating to the Western Unitarian Conference and Western Unitarian Sunday-School Society are at the library of Meadville-Lombard Theological School in Chicago, Illinois. In addition to works mentioned above Buck also wrote Religious Education for Democracy (1919), How We Use the Bible in Religious Education (n.d.) and Grading a Small Sunday School (n.d.). Short biographies of Buck include William Lawrance, “Florence Buck: In Memoriam,” Christian Register (5 November 1925); Catherine F. Hitchings, “Universalist and Unitarian Women Ministers,” The Journal of the Universalist Historical Society (1975); and Alice Anne Conner, “The Reverend Florence Buck: Crusader for Women,” Kenosha News (19 October 1994). For information on the Iowa Sisterhood consult Cynthia Grant Tucker, Prophetic Sisterhood: Liberal Women Ministers of the Frontier, 1880-1930 (1990). Mary C. Boys, Educating in Faith: Maps and Visions (1989) and Lawrence Cremin, American Education: The Metropolitan Experience 1876-1980 (1988) provide background for Buck’s education and religious education theory.

Article by Melissa Ziemer

Posted May 28, 2002