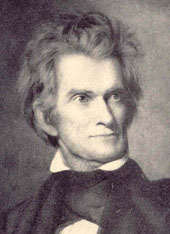

John Caldwell Calhoun (March 18, 1782-March 31, 1850) was a United States representative, senator, secretary of war, secretary of state, and vice president. A political sparring partner to John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Daniel Webster, and Henry Clay, Calhoun is best remembered for the rallying cries of “states’ rights” and “nullification,” both of which he invoked to support his steadfast opposition to tariffs on manufactures and his defense of slavery.

John C. Calhoun was born in Abbeville, on the frontier of South Carolina, the fourth child, third son of Scots-Irish immigrant Patrick Calhoun and his second wife Martha Caldwell. Patrick was a landowner, a farmer, a legislator, an anti-Federalist political activist, and a slave owner. At a very early age John heard his father’s fulminations against ratifying the Constitution.

Education was hard to come by in the backwoods of South Carolina. John intermittently attended a school run by his brother-in-law, Moses Waddel, read voraciously, and acquired a taste for politics and history. The family recognized his academic gifts and, with his reluctant consent, decided to prepare him for a profession. After two years at Waddel’s school, in the fall of 1802 Calhoun entered Yale, where he excelled as a student.

Calhoun was raised a Calvinist, and remained a philosophical Calvinist in his firm work ethic, his resistance to such simple pleasures as dancing, and his bleak view of human nature. He was nevertheless strongly attracted to the philosophical and rational orientation of the emerging liberal tradition. Calvinist Timothy Dwight, the President of Yale, could not persuade Calhoun even to profess a faith in Christianity. It was at Yale that Calhoun first encountered Unitarian ideas, years before the formal split between Unitarian and Calvinist Congregationalists.

After graduating from Yale in 1804 and a brief interlude studying law in a Charleston, South Carolina law firm, Calhoun returned to Connecticut to study at Litchfield Law School, a hotbed of Federalist (and secessionist) politics. Returning to South Carolina, he was admitted to the bar in 1808 and began courting his cousin Floride Colhoun, whom he married in 1811. The Calhouns settled first in Long Cane and later near Pendleton in the upper corner of South Carolina on a plantation called Fort Hill, where Calhoun divided his attention between his three passions of politics, farming, and family. Cotton was the main crop at Fort Hill, and slaves did much of the farming and household management.

John and Floride had nine children, seven who survived to adulthood, including his beloved daughter and confidante Anna Maria. Anna Maria, who inherited Fort Hill, married a Philadelphia engineer, Thomas Clemson. After the death of his wife and their two children, Clemson willed the Calhoun plantation to the state for a public university (Clemson University).

Calhoun was first elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1811. He brought to this new role the combination of a plantation upbringing and a New England education, with friends and colleagues from both North and South. Early in his career Calhoun was an ardent nationalist, a supporter of the War of 1812 against England, and a cautious supporter of the 1816 tariff (always a point of contention between North and South) as a source of revenue to replenish the Federal treasury after the war. His reservations about this tariff stemmed from its being advocated by northern manufacturers who wished to extend the favored status they had enjoyed during the British blockade, at the expense of the South, which wanted to export cotton and other agricultural products and buy cheaper European manufactures. At that time he also supported some centralizing policies, favoring renewal of the charter of the fledgling Bank of the United States and a federal role in creating transportation networks to encourage industry and development.

Calhoun left Congress in 1817 to serve ably as Secretary of War in the Monroe administration, rising to prominence on the national stage at age 35. Although in 1822 he was considering a run for the presidency, competition from John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson forced him to step back. Deadlocked in a three-way contest with Clay and Jackson in the Electoral College, Adams was chosen president by the House of Representatives. Calhoun, on the other hand, was elected Vice-President with a clear majority in the Electoral College. Thus he had a greater mandate than the new president, his political rival and fellow Unitarian. Presiding over the Senate, he was a leader of the opposition to the Adams administration.

In 1828 Calhoun was re-elected Vice-President, once again serving with a President, Andrew Jackson, with whom his relationship was less than cordial. By the middle of the four-year term, mutual mistrust had evolved into open hostility. The most intense conflict centered around the 1828 tariff law, nicknamed the “Tariff of Abominations,” which Calhoun opposed as detrimental to the interests of the South and the preservation of the Union. While protecting northern manufactures this tariff made it more difficult for southern trade with Europe. The South, particularly South Carolina, was outraged. It was in a speech in response to this tariff that Calhoun first articulated the doctrine of nullification.

The nullification doctrine was Calhoun’s first line of defense for the protection of minority rights against the tyranny of the majority, particularly the rights of southern agricultural slave-owners against the rising power of northern capitalists. Nullification was a special instance of the older notion of “states’ rights.” He claimed that states have the right to refuse to enforce (to nullify) a federal law with which they do not concur. In South Carolina, however, the nullifiers threatened secession if the Tariff of 1828 was not withdrawn. President Jackson warned that he would use armed force to preserve the Union. In order to avert civil war, Calhoun reluctantly collaborated with his political opponent Henry Clay to craft the Compromise Tariff of 1833.

Calhoun’s chief opponent in the Jackson cabinet was Secretary of State Martin Van Buren. As part of a reorganization designed to purge the cabinet of Calhoun’s nullifying influence, Van Buren was appointed Minister to England. In the waning days of 1831 Calhoun prevented Senate confirmation of Van Buren’s appointment, casting the deciding vote as the Senate’s presiding officer. This victory was to prove short-lived. Another cabinet member, Secretary of War and former Tennessee senator John Eaton, had recently married a woman with a scandalous reputation. When Floride Calhoun snubbed Peggy Eaton, it was yet another nail in the coffin of Calhoun’s presidential ambitions. In 1832 Jackson selected Van Buren to run for Vice President.

Although Calhoun began his political career as a nationalist, by the mid-1820s he had begun to identify closely with his home state and region in the sectional conflict over both tariffs and slavery. Like another slave-holding southern Unitarian, Thomas Jefferson, Calhoun was shaped in an agrarian culture that mistrusted industry and urbanization. A hands-on farmer in his early days, he later enjoyed extended visits to his Fort Hill plantation as respites from national politics. He never wavered from the defense of slavery, and foresaw chaos and economic hardship for Southern blacks and whites alike if slavery, the foundation of Southern agriculture, were to end abruptly.

It was in this context that Calhoun fashioned his second contribution to political thought, the doctrine of “concurrent majorities.” He was distrustful of simple majorities, which allowed one group, class, or region to override and disregard the different needs and values of another. According to Calhoun, any policy that is potentially divisive, one that greatly benefits one group at the expense of another, should require separate concurrency by coalitions of states, regions, or interests. Despite its original use to protect the institution of slavery, the idea of concurrent majorities has since gained respectability as a means of accommodating diversity within a heterogeneous society.

After Jackson’s re-election, Calhoun returned to the Senate, where he remained for much of the rest of his career. Although the slavery issue was becoming increasingly divisive, there were other issues to occupy his attention. He continued battles begun in the Jackson administration against the spoils system and political patronage.

In 1840 the Whig ticket of William Henry Harrison (who died a month after taking office) and John Tyler defeated President Van Buren’s bid for re-election. Senator Calhoun for the first time found himself allied with the President, as Tyler was also a slave-owning southern conservative. Calhoun also sided with Tyler in opposition to a central bank. In 1843, he resigned from the Senate in order to make another try for the Presidency. When Tyler’s Secretary of State, Abel Upshur, was killed in an explosion in early 1844, Calhoun was called back to Washington to take his place. During his short tenure as Secretary of State he addressed two difficult issues, the annexation of Texas and the resolution of the northwest boundary dispute with England.

Calhoun spent his remaining years back in the Senate, his lifelong quest for the presidency thwarted by political and sectional rivalries and the rising tide of opposition to slavery. In his last speech to the Senate on the admission of California to the Union as a free state, 27 days before his death in 1850, he reiterated his positions on states’ rights and foresaw bleak prospects for the continuation of the Union.

Calhoun’s oratorical style was different from the florid and impassioned speeches of Daniel Webster and Henry Clay. Rather, his speeches reflected his exceptionally keen mind, legal training, and devotion to reason. He analyzed the underlying values and conflicts of issues and applied his political theories to resolve them. In both religion and politics he thought the same way: he was rational, consistent, factual, and resistant to either emotional pleas or divine commands.

Along with his nemesis John Quincy Adams, Calhoun was one of the founders of All Souls Unitarian Church (established 1822) in Washington, D.C. He contributed generously to the cost of the church’s construction and attended services there. His family, however, was not similarly inclined; his mother-in-law remained a devout Presbyterian and his Episcopalian wife would not attend services at the new Unitarian Church although it was just a few blocks from their home. Calhoun’s religion was largely a private matter, one rarely referred to in his writings or public utterances.

The Calhoun papers are at the University of South Carolina, in Columbia, South Carolina. A 26 volume edition of his papers has been published under the editorship of W. Edwin Hemphill, Robert L. Meriwether, and Clyde Wilson, The Papers of John C. Calhoun (1959-2001). A selection of Calhoun’s papers edited by Ross M. Lence has been issued as Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun (1992).

Calhoun has been the subject of numerous biographies, some laudatory, others damning. A selection of perspectives on Calhoun’s life is provided in John L. Thomas, ed., John C. Calhoun: A Profile (1968). Margaret L. Coit’s John C. Calhoun: American Portrait (1950), a lively account of his life and work, won the Pulitzer prize. Ernest M. Lander, Jr., a retired history professor at Clemson University, authored The Calhoun Family and Thomas Green Clemson: The Decline of a Southern Patriarchy (1983). John Niven has an excellent and balanced biography, John C. Calhoun and the Price of Union: A Biography (1988). Perhaps the most comprehensive biography is Charles M. Wiltse’s three volume John C. Calhoun (1944): Nationalist, 1782-1828; Nullifier, 1829-1839; and Sectionalist, 1840-1850. While many of Calhoun’s biographers skirt the issue, and his papers make few references to his religious affiliation, biographers Charles Wiltse and Ernest Lander identify him as a Unitarian.

Article by Holley Ulbrich

Posted March 6, 2003