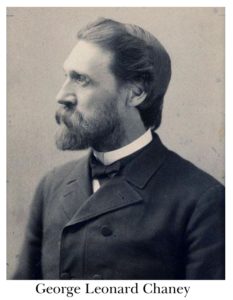

George Leonard Chaney (December 24, 1836-April 19, 1922) was an established New England Unitarian minister whose major contribution to Unitarianism was his work in the southern United States following the Civil War. Although his orthodox Liberal Christian theology placed him on the conservative end of the Unitarian spectrum, he was a visionary who brought Unitarianism to the south. After serving congregations in Boston Massachusetts, Chaney relocated to the south in 1882 where he served congregations in Atlanta, Georgia and Richmond, Virginia, and as the first Southern Superintendent of the American Unitarian Association. As Southern Superintendent, he was instrumental in founding congregations across the south. To further spread the Unitarian message, Chaney founded and edited The Southern Unitarian. A strong supporter of education, Chaney especially believed in the value of “manual” or “industrial” training as a way to improve the lives of the disadvantaged, including former slaves and their children. He was a strong supporter of African American education, especially Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, Tuskegee Institute, and Atlanta University. Chaney began his southern ministry when he arrived in Atlanta in early 1882 as a missionary of the American Unitarian Association (AUA) to explore the possibility of establishing a Unitarian church in that city. The idea of starting a congregation of a liberal New England religion, strongly connected to the Abolitionist Movement, seventeen years after the Civil War in the Deep South was a daunting undertaking. Nevertheless, Chaney succeeded.

George Leonard Chaney (December 24, 1836-April 19, 1922) was an established New England Unitarian minister whose major contribution to Unitarianism was his work in the southern United States following the Civil War. Although his orthodox Liberal Christian theology placed him on the conservative end of the Unitarian spectrum, he was a visionary who brought Unitarianism to the south. After serving congregations in Boston Massachusetts, Chaney relocated to the south in 1882 where he served congregations in Atlanta, Georgia and Richmond, Virginia, and as the first Southern Superintendent of the American Unitarian Association. As Southern Superintendent, he was instrumental in founding congregations across the south. To further spread the Unitarian message, Chaney founded and edited The Southern Unitarian. A strong supporter of education, Chaney especially believed in the value of “manual” or “industrial” training as a way to improve the lives of the disadvantaged, including former slaves and their children. He was a strong supporter of African American education, especially Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, Tuskegee Institute, and Atlanta University. Chaney began his southern ministry when he arrived in Atlanta in early 1882 as a missionary of the American Unitarian Association (AUA) to explore the possibility of establishing a Unitarian church in that city. The idea of starting a congregation of a liberal New England religion, strongly connected to the Abolitionist Movement, seventeen years after the Civil War in the Deep South was a daunting undertaking. Nevertheless, Chaney succeeded.

Chaney was born on Christmas Eve 1836 in Salem, Massachusetts. His parents, James and Harriet Webb Chaney, were both from prominent families who traced their ancestors to the first Puritan settlers of New England. Chaney graduated from Harvard with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1859 and was a member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. After graduation he went to Meadville, Pennsylvania, as a tutor in the family of Mr. Edward Huidekoper. He enrolled in the Meadville Theological Seminary and graduated in 1862. He was called to Boston’s Hollis Street Church in July of that year where he followed distinguished minister Thomas Starr King who had resigned two years earlier to accept a call to San Francisco. To follow such a notable preacher to the Hollis Street pulpit must have been a challenge for a young and inexperienced minister. Adding to Chaney’s challenge was the long history of conflict between the Hollis Street congregation and their clergy.

The congregation’s first minister, Mather Byles, was dismissed in 1776 for his Tory sympathies and for having “pray’d in publick that America might submit to Grate Brittain.” A more recent conflict ensued when long-serving minister, and Starr King’s predecessor, John Pierpont began preaching on the “exciting topics” of abolition and temperance. Many of the wealthy members of his congregation were merchants who made their fortunes in the rum trade and were, at best, ambivalent about slavery. Pierpont was pressured to resign, but he refused and demanded a trial. The council of ministers that was convened to hear the case criticized Pierpont, but eventually cleared him of all charges. However, continued pressure from the church’s wealthy members finally forced Pierpont to resign in 1845. By all accounts Chaney’s ministry was successful. The minutes of the meetings of the Hollis Street Church proprietors during Chaney’s tenure do not show any accounts of ministerial conflicts. Chaney’s clerical talents were demonstrated by a call, four years into his Hollis Street ministry, from the Providence, Rhode Island church. The vote to call Chaney was unanimous and included a $2000 per year increase in salary. However, Chaney declined the offer and served the Hollis Street Church for fifteen years, resigning in 1877.

During both Chaney’s education at Harvard and Meadville and his early ministry, the most vexing political issue facing the nation was the question of slavery. Like many Unitarian clergy, Chaney considered slavery to be evil, but he was not outspoken on the issue. In 1865 he preached a eulogy at Hollis Street Church on the death of Abraham Lincoln. Chaney praised Lincoln for his “fair-dealing which led him to offer, again and again compensated emancipation to the slave-master” and for refusing demands to repeal the Emancipation Proclamation. Quoting Lincoln; “to abandon them [the freed slaves] now would . . . be a cruel and astounding breach of faith.” In a later, 1880, essay on William Ellery Channing, “Channing’s Relation to the Charities and Reforms of His Day,” Chaney noted that the abolitionist “zealots” criticized Channing for being “timid and time-serving” because of his cautious approach and reluctance to condemn slavery. However, Chaney pointed out that when Channing began to speak out on slavery, “he moved slowly, steadily, serenely, but with terribly accumulating clearness of view,” and continued to speak out until his death in 1842. Chaney’s moderate stance on slavery and lack of identification with the Abolitionist Movement no doubt helped him to be accepted by Southern society when he began his Atlanta ministry.

In 1865 Chaney was a delegate to the first meeting of the National Conference of Unitarian Churches founded by Henry W. Bellows and regularly attended its annual meetings. Bellows, like Chaney, had been a moderate on the slavery issue and formed the conference in order to provide a more effective organizational structure than the loosely organized American Unitarian Association. One of the major goals of the National Conference was to spread Unitarianism and to establish new churches. Chaney also served on the board of the American Unitarian Association from 1871 until 1883.

In 1865 Chaney was a delegate to the first meeting of the National Conference of Unitarian Churches founded by Henry W. Bellows and regularly attended its annual meetings. Bellows, like Chaney, had been a moderate on the slavery issue and formed the conference in order to provide a more effective organizational structure than the loosely organized American Unitarian Association. One of the major goals of the National Conference was to spread Unitarianism and to establish new churches. Chaney also served on the board of the American Unitarian Association from 1871 until 1883.

Chaney was a firm believer in the value of manual or industrial education and urged the Boston School committee to add it to the public school curriculum. The committee declined until they could see the efficiency of the program. In the winter of 1866, along with several other Boston gentlemen, Chaney organized the “Hollis Street Whittling School,” which was designed to train poor boys with skills that they could use in various trades. According to Chaney, the school began with “about thirty little street Arabs – boys that we selected at random out of the gutter.” Chaney believed that manual training not only gave the students a way to earn a living, but that it also instilled a sense of pride that would improve them morally. As he later put it, manual training made the students “self-reliant, independent and self-respecting.”

In 1867 Chaney journeyed to Virginia to visit schools established by the Soldier’s Memorial Society. This organization was established at the end of the Civil War by men and women who had either served in or had worked for the army to assist in the reconstruction of the south. In cooperation with the Freedman’s Bureau, the society established and supported schools for both black and white students. Upon his return, Chaney reported on his trip in a sermon entitled “Reconstruction through Education at the South.” In it he supported the position of the Soldier’s Memorial Society that the Southern states were failing to educate the poorer classes and that the schools and teachers supported by the society were essential to the reconstruction of the south.

Chaney’s interest in the value of manual education led him to become an early supporter of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, which had been created following the Civil War by the Freedman’s Bureau and the American Missionary Association to educate recently freed slaves. The leader of the school, General Samuel C. Armstrong, had grown up in Hawaii as the son of missionaries and had patterned Hampton after the Hawaiian missionary schools of his youth, specifically the Hilo Boarding and Manual Labor School for Boys. According to Armstrong, by stressing manual training this school produced “less advanced but more solid men” (men who were less educated, but of higher moral character) than other missionary schools that taught “higher branches” of education. Armstrong adapted the Hilo system to Hampton, which offered “generally elementary and industrial teaching” as a way to train the “hand, head and heart.” To obtain adequate funding for his school, Armstrong turned to wealthy Northerners for donations. In January of 1870 the Boston Hawaiian Club put on a gala benefit for Hampton. Prior to the event, Chaney was part of a delegation of members who were asked to visit the school and to report on its methods and operation. Chaney’s glowing description of the school was printed in the Boston Transcript and helped make the occasion a success.

Chaney believed that education for students of both races was the key to the reconstruction of the south. In the spring of 1870 he traveled to Wilmington North Carolina to visit a school for “the poorer white population.” The school had been established by Miss Amy Bradley in 1867 with the backing of the American Unitarian Association and the Soldier’s Memorial Society. Upon his return he gave a sermon to his Hollis Street congregation entitled “Women’s Ministry, as Exemplified in Southern Schools,” which extolled both the schools and the women who ran them. He noted that he had visited schools in Richmond, Hampton, Charleston, Jacksonville, as well as in Wilmington – all primarily run by women who he felt had been “divinely called, and have been providentially fitted, to carry out the grandest missionary work of the century.” In a forward thinking statement on the rights of women, he declared that “the man who would deny to woman the power of command and authority had not fully searched her character and accomplishments.” After hearing his sermon, one of his wealthy members, Mrs. Augustus Hemenway, was moved to support the Wilmington school and donated $5000 per year for ten years. Chaney was an adept fundraiser and was able to tap into his network of wealthy Bostonians to encourage them to support his causes.

In January 1871 Chaney married Caroline Carter who was also from a prominent New England family. She was descended from one of the early Puritan settlers, the Rev. Thomas Carter, who arrived in New England in 1635. The Carters had branches in New England and Virginia, as well as members who were successful planters in Hawaii. The couple had one son, George, who was born in November, 1871.

Chaney was also a strong advocate of literacy and wrote several books for boys beginning with F. Grant and Co. or Partnerships: a Story for the Boys who “Mean Business” in 1875. He followed with another book for boys, Tom: A Home Story, in 1877. The theme of both books was how to succeed in life through teamwork and mutual support. Caroline Chaney also had a notable literary career as a poet and author, including a play “William Henry,” which was based on a book by Mrs. A. M. Diaz, the William Henry Letters. Like her husband’s work, Caroline Chaney’s play was a morality story for a young audience.

After fourteen years at the Hollis Street Church, Chaney took a ten month sabbatical, and along with his wife and son, made an extended trip to California and on to Hawaii to visit his wife’s relatives. In 1880 he published an account of their Hawaiian trip, Alo’ha! A Hawaiian Salutation. In Hawaii, Chaney was impressed by the work of the missionaries and their efforts to bring Christianity to the native Hawaiians. In his book Chaney discussed his impressions of the exclusive Punahou School “where the youth of the islands receive their higher education.” He went on to note that “many of the best citizens of America” were Punahou alumni including “our friend [Gen. Samuel C.] Armstrong, of Hampton Va., who learned in the Hawaiian Islands the secret of his successful treatment of the freedmen of the South.” Punahou was established to educate the children of the missionaries and planters, while Hilo, the school that Armstrong used as his model for Hampton, was created to train the native Hawaiians to become laborers on the pineapple plantations.

The year following his return, Chaney decided to leave the Hollis Street pulpit. The neighborhood was becoming industrialized, and he felt that it would be impossible to maintain the congregation as a family church. Most of the neighboring churches had already moved, and Hollis Street Church soon followed. It eventually merged with Edward Everett Hale’s South Congregational Society.

In the years following the Civil War, both the National Conference and the American Unitarian Association attempted to expand Unitarianism beyond its New England roots by sending missionaries to the Western and Southern states. The south would prove to be especially challenging. In 1881 Rev. Enoch Powell came to Atlanta to ascertain the possibility of establishing a church. Apparently, he did not see Atlanta as fertile ground for Unitarianism and after a few months, according to the Atlanta Constitution, he left “to return to other fields of labor.” Powell appears to have been graciously received by the local leaders, and the article in the local newspaper announcing his departure went on to say that future effort to establish a Unitarian church in Atlanta “will receive the deserved support of the Constitution.”

Despite Powell’s lack of success, Chaney, who was serving on the board of the American Unitarian Association, accepted the challenge to, according to the January 9, 1882 board minutes, “visit Atlanta, Georgia, and preach there.” It seems that Chaney’s trip was not seen as a permanent move, and no one in Boston appeared to be optimistic about the odds of establishing an Atlanta church. However, when Chaney arrived in early 1882, he was welcomed by both the civic and business leaders of Atlanta. One reason for his cordial reception can be found in the announcement of his arrival in the Atlanta Constitution, which noted that he “had labored for the cause of industrial education with Mr. Edward Atkinson, of Boston.”

Edward Atkinson was a forward-thinking textile and insurance executive in Boston who had been an active abolitionist, a member of the Boston Vigilance Committee led by radical Unitarian minister Theodore Parker and had helped raise money to support John Brown’s partisan warfare in “Bleeding Kansas.” He was also a recognized authority on cotton production. Following the war, cotton manufacturers in the north were concerned with the inefficient harvesting methods and the poor quality of the cotton that they were receiving from the south. In a case of odd bedfellows, Atkinson teamed with Atlanta’s political and business leaders to organize a cotton exposition to be held in Atlanta to bring Southern cotton growers and Northern manufacturers together in order to meet and learn from each other. The International Cotton Exposition, held between October and December of 1881, was a great success and brought thousands of visitors to Atlanta, including General William T. Sherman. It was a major factor in stimulating the economic growth of the “New South.”

Chaney’s friendship with Atkinson eased his acceptance by Atlanta’s leaders. Governor Alfred Colquitt, a former Confederate General who had worked with Atkinson on the Cotton Exposition, even allowed Chaney to hold his initial services in the Georgia Senate Chamber. After a few services in the Senate Chamber, Chaney moved to Concordia Hall and then to the U.S. District Court Room in the Federal Post Office building, which had drawbacks. One critic, Chaney recalled, declared that “she would not go to that Yankee Courthouse to hear Saint Paul preach.” “Needless to say,” Chaney added, “that she did not come to hear me.” Finally, “with a lot of patience . . . added to faith,” the first Unitarian church in Atlanta was organized as “The Church of Our Father.” Their new church home was officially dedicated on April 24, 1884 with the participation of Unitarian clergy from Charleston, New Orleans and Cincinnati, who met later that week to form the Southern Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches. The conference was to facilitate the establishment of other Unitarian churches in the south. At the time of the founding, there were only three Unitarian Churches reported to be functioning in the South – Charleston, New Orleans, and the newly founded Atlanta congregation.

Both Chaney and his wife became respected and active members of Atlanta society. They were members of the Georgia Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and Rev. Chaney served on the Board of Directors of the Young Men’s Library Association where he was elected vice-president in 1888 and president in 1889. The church also maintained a small library primarily for the use of church members. Some writers have claimed that Chaney opened it to African-American as well as white patrons, which would have been a drastic move in 1880’s Atlanta. No record has been found of Chaney making such a claim, nor has a record been found of it being reported in the local newspapers or of it being discussed by the church’s board of directors. Such a radical policy could not have been implemented without intense discussion by church leaders, and given that the church and Chaney received much positive newspaper coverage, it is inconceivable that an integrated church library would have escaped the notice of the local press.

It should be noted that while serving as board member and president of the Young Men’s Library Association, Chaney made no effort to integrate its facility. However, he was concerned about the lack of reading material available for African American students. In a sermon entitled “Juvenile Literature and Juvenile Morals” published in a collection of his sermons, Every-day Life and Every-Day Morals, Chaney advocated for separate libraries to provide quality reading material for “colored boys and girls.” “There ought to be free libraries and reading rooms in all centres of population for the graduates of our colored schools,” otherwise he feared they would be left to read the “cheap daily and weekly papers or periodicals . . . that will only make them wise unto damnation.”

Soon after arriving in Atlanta, Chaney was interviewed by the Atlanta Constitution in which he laid out his philosophy about the importance of manual education. He stressed the need for manual education for African American noting that when “dealing with the colored race . . . they should be taught useful trades [because] the professions are not as generally open to them as they are to whites.” Chaney’s passion for industrial education drew him to the efforts of Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute.

Tuskegee was chartered in 1881 by the Alabama legislature. General Armstrong of the Hampton Institute was asked to recommend a white man to serve as principal. Instead, he recommended one of his most promising African American students, 25 year old Booker T. Washington, for the position. Washington based Tuskegee’s curriculum on the Hampton philosophy of manual education. Chaney became a strong supporter of Tuskegee and helped Washington raise funds from wealthy Boston Unitarians. He served on the board from 1883 until 1904 and was board Vice-President in 1901. He also spoke at the dedication of Tuskegee’s first building, Porter Hall, in 1883.

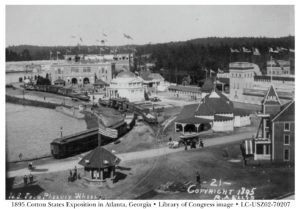

Booker T. Washington saw manual education as the best way to uplift African Americans by providing them a path to economic security. To accomplish this goal, he urged African Americans to forgo seeking equal rights and rather to strive for economic opportunity as skilled laborers. His approach was laid out in his famous “Atlanta Compromise Speech” given at the Atlanta Cotton States Exposition in 1895. In it he urged African Americans to accept second class citizenship, arguing that “the wisest among my race understand that the agitation of questions of social equality is the extremist folly.” Washington also endorsed racial segregation, “in all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one in all things essential to mutual progress.” Washington was echoing the attitude of the white establishment – both North and South – that the black race was not ready for full civil rights, and that they needed moral as well as intellectual uplift. Chaney fully supported Washington’s approach. As he wrote to Washington a few years after the speech, “I more than ever believe in your way of solving the political problem, by flanking prejudice with intelligence, character and wealth.” Chaney’s support of the industrial education for African Americans needs to be put into context. By supporting Booker T. Washington’s program, Chaney was tacitly supporting second-class citizenship for African Americans. White Americans – north and south – were less threatened by Washington’s vision of black industrial training than by schools that educated African Americans to the same level as white college graduates.

One such school was Atlanta University (now Clark/Atlanta University), which, like Hampton, had been founded by the American Missionary Association and the Freedman’s Bureau. Unlike Hampton and Tuskegee however, Atlanta University’s goal was to provide a classic college education for African American students, but its leaders realized that schools that offered an industrial education found it easier to raise funds from white donors. In his interview with the Atlanta Constitution, Chaney noted that Atlanta University wanted to add a “department of practical education for both sexes,” and that “I am satisfied that I can raise the money for this purpose in Boston.” It seems that Chaney was successful. In 1884 the building for the “mechanical department” was erected with a $6,000 donation from the estate of L. J. Knowles, a wealthy loom manufacturer from Worcester Massachusetts. That same year, Chaney was elected to the school’s Board of Trustees, where he served until 1889.

Following the example of his Hollis Street School, in 1885 Chaney, along with several church members, founded the Atlanta Artisans Institute, which provided instruction in “iron and wood working, mechanical drawing, and machine construction” for up to forty (white) students. At the same time that the Artisans Institute was in operation, there was a growing realization that Georgia needed a larger, state funded technical school if the state was to compete in the “New South” era of economic growth and industrialization.

Some biographers have claimed that the Artisan Institute evolved into The Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), and that by extension Chaney was the founder of that school. This assertion is based on a misinterpretation of Chaney’s recollection that one of the philanthropic efforts of the Atlanta Church was “the Artisans Institute which led the way for the School of Technology.” In 1885 the Georgia Legislature passed a bill authorizing the creation of a school of technology, which set off a competition among Georgia towns (Macon, Milledgeville, Athens, Columbus, as well as Atlanta) vying to offer the best “inducements” to put the new campus in their locales. Atlanta won out because as Chaney said, it was “secured to Atlanta by the munificent contributions of its citizens.” Given his passion for industrial education, Chaney no doubt supported the creation of the school, but there is no evidence that the Artisan’s Institute led to the founding of Georgia Tech or that Chaney was directly involved in its creation. When the school formally opened on October 5, 1888, Chaney was not among the distinguished citizens listed as attending the ceremonies. Chaney did attend Georgia Tech’s first commencement, but there is no mention of his participation other than that of a spectator. In his comment, Chaney was simply stating that the Artisan’s Institute preceded the founding of Georgia Tech, not that it became Georgia Tech.

In 1890, after twenty years of ministerial experience, Chaney was appointed Southern Secretary of the American Unitarian Association (AUA). He felt that it was time to leave the Atlanta church in order to devote more time and energy to spreading Unitarianism to other Southern cities. After leaving Atlanta, Chaney moved to Richmond, Virginia, which he considered to be the “Jerusalem of the South.” Unlike Atlanta, which was virgin territory for Unitarianism, Richmond had a long, if difficult, experience with liberal Christianity. In 1824 Universalist missionary William Hagadorn spent six months preaching in Richmond, but did not organize a permanent church. In 1830 Universalist John B. Dods spent ten weeks in Richmond and organized the Unitarian and Universalist believers in the region into the Unitarian-Universalist Society. Dods returned north, and the society called Universalist John B. Pitkin as their minister. In January 1833 the members dedicated their new building and adopted the name First Independent Christian Church. It is believed to have been the first combined Unitarian Universalist congregation in America, predating the merger of the two denominations by 128 years. After Pitkin left in 1835 due to poor health, the fortunes of the church waxed and waned through a series of ministers. The church’s status was not helped by their association with Northern denominations closely identified with the anti-slavery movement. In January 1861 the congregation called Universalist Rev. Alden Bosserman from Baltimore as their minister. Bosserman seem to be a safe choice for a Southern congregation since he brought his slave with him. Nevertheless, in March 1862 he was arrested by Confederate authorities as a Union sympathizer. He was later released and sent north as part of a prisoner exchange. With their minister’s arrest, the church essentially dissolved and the building fell into decay.

It is not known exactly when Chaney arrived in Richmond, but by December 10, 1892 he was holding services in Belvidere Hall on Main Street. On December 31 of the following year, eighteen people signed as charter members of the First Unitarian Church of Richmond, and Chaney was formally named as minister with his salary to be paid by the AUA. One of the charter members, Mary F. Hill, had been a member of the original church. She brought to the new church a Chippendale pulpit chair that she had rescued from the original building and had kept safe during the destruction of the Civil War. It now sits in the minister’s study at the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Richmond.

While serving as minister to the Richmond congregation, Chaney was also the Southern Superintendent of the American Unitarian Association as well as editor of the regional Unitarian publication, The Southern Unitarian. Since his duties as Southern Superintendent required that he travel frequently, a recent Meadville graduate, Rev. Joseph M. Seaton, was called as assistant minister. Now able to devote more time to his duties as Southern Superintendent, Chaney traveled extensively throughout the south. In December 1894 the Richmond Dispatch reported that Chaney had just returned from an extended trip in which he attended the National Conference in Saratoga New York, visited churches in Cincinnati, St. Louis and Louisville, followed by visits to “all or nearly all of the Unitarian churches and missions in the South, from Virginia to the Lone Star State.” Chaney was also present for the opening day of the 1895 Atlanta Cotton States Exposition when Booker T. Washington gave his famous Atlanta Compromise speech. He spoke about it the following year to both the Richmond and Atlanta churches and noted that both “Anglo-Saxon and African [Washington] stood on the same platform” to give their speeches, which was considered radical at the time.

Through Chaney’s efforts, Unitarian churches or societies were founded in Chattanooga Tennessee, Asheville and Highlands North Carolina as well as San Antonio, Austin, Dallas and Fort Worth Texas. Other attempts to establish churches in Memphis Tennessee and Birmingham Alabama were hindered by what Chaney described as “ministerial misfit.” He also supported groups of “scattered believers” who were served by Circuit Ministers in Florida, North Carolina and Texas. One of these circuit ministers, Jonathan Gibson, was from a slave-owning family and had served as a private in the Confederate Army. Originally a Baptist, he became a Unitarian after meeting Chaney. Gibson established a small congregation in Bristol, Florida and served his congregation and other groups in Florida and Georgia for twenty years.

At the January 14, 1896 board meeting of the American Unitarian Association, a lack of funds forced a curtailment of missionary efforts, which led Chaney to offer his resignation as Southern Superintendent. The board appropriated a half year’s salary to allow Chaney to continue his efforts for six months and voted to express their appreciation for the “gifts of mind and heart and the spirit of self-sacrifice” that both Chaney and his wife had brought to their work. Caroline Chaney was an important part of her husband’s work and served as the president of the Southern Associate Alliance, the women’s auxiliary of the Southern Conference. At the 1895 National Unitarian Conference in Washington, D.C. she presented a paper on the work of Southern Unitarians, “The Southern Opportunity,” which supported her husband’s efforts to expand Unitarianism in the south. In addition she had been active in various civic organizations such as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Atlanta and had supported a Day Nursery and Free Kindergarten in Richmond.

During the last six months of his term, Chaney and his wife made extended trips “to strengthen the churches in the South,” and to prepare them to become self sufficient. His trips took him to all points of the South, and in April 1896, they traveled to Louisville Kentucky to attend his final meeting of the Southern Conference, which he had founded twelve years earlier. In May Chaney spoke at the commencement exercises at Tuskegee Institute and presented the diplomas to the graduates of the Bible Training School.

At the end of his term, Chaney retired and returned to Massachusetts to spend time between his home in Salem and his wife’s farm in Leominster, with occasional trips to Florida and Jamaica. Retirement however, did not stop his activities. He remained on Tuskegee’s board until 1904 and was vice-president in 1901. In January 1900 he preached at the Unitarian church in New Orleans, and in November 1915 he returned to Atlanta to attend the dedication of the new church building, now renamed The Unitarian Church of Atlanta. At the service, the stained glass window at the front of the church was dedicated in honor of both Rev. Chaney and his wife, Caroline. Today the top portion of the window is located at the Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Atlanta and the lower section is at the sister church, the Northwest Unitarian Universalist Congregation, also in Atlanta.

Rev. George Leonard Chaney died on April 19, 1922 at his home in Salem, Massachusetts. He was a devoted Unitarian clergyman and a gifted orator with a dry sense of humor. He dedicated himself to both bringing Unitarianism to the southern states and to supporting education, especially manual education for both poor whites and for African Americans. Racially and socially he was a man of his time. He was from the affluent Boston Brahmin social class and had a paternalistic attitude toward both poor whites and members of other races, be they native Hawaiians or African Americans. Nevertheless, he would have been considered a racial progressive, especially in the post Civil-War South.

As a respected member of Boston’s Unitarian clergy, he could have comfortably ministered to a church in his native New England, but instead chose to accept the challenge to bring Unitarianism to a region where other feared to tread. Both he and Mrs. Chaney were able to overcome the challenge of being associated with a denomination associated with the abolitionist movement and were accepted and honored by both Atlanta and Richmond societies. He was a remarkable man who persevered where others would have faltered. Without his persistence and dedication, it is possible that there would not be the Unitarian-Universalist presence in the South that we have today.

Sources

The George Leonard Chaney papers are in the Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Collection at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia (an on-line finding aid is available at emory.edu). Additional Chaney documents are available on-line in the Unitarian Universalist Digital Archive at nwuuc.org/archive/. The Andover-Harvard Theological Library Archives in Cambridge, Massachusetts has a ministerial file for Chaney and 44 letters to Edward Everett Hale. A short biography of Chaney, a CDV portrait, and a digitized copy of the “Hollis Street Church Records, 1862-79” are available on-line at: library.hds.harvard.edu.

In addition to the books and articles mentioned in the text above, Chaney published, Hollis Street Church from Mather Byles to Thomas Starr King, 1732-1861: Two Discourses Given in Hollis Street Meeting-House, Dec. 32, 1876 and Jan. 7, 1861, (1877); “Report of the Southern Conference,” in the Official Report of the Proceedings of the Eleventh Meeting of the National Conference of Unitarian and other Christian Churches, (1884); Every-Day Life and Every-Day Morals (1885); and “The New South Atlanta,” New England Magazine, (November, 1891). In his book Belief (1889), Chaney explores the interplay between Christian beliefs and the emerging scholarship of comparative philology, eastern religions, and science. Chaney also penned the biography “Henry Wilder Foote: 1838-1889” in Samuel A. Eliot, ed., Heralds of a Liberal Faith: The Preachers, Vol 3 (1910). A two page biography, “George Leonard Chaney: 1836-1922,” written by Henry Wilder Foote II (1875-1964) can be found in Samuel A. Eliot, ed., Heralds of a Liberal Faith: The Pilots, Vol 4 (1952). This biography also covers Cheney’s southern co-workers; Amory D. Mayo and Pitt Dillingham. A digital copy of Heralds of a Liberal Faith: Volume 4 can be accessed at archive.org. Also of great interest is William R. Gowen, “George Leonard Chaney: A Rediscovered Nineteenth Century Perspective,” in The Horatio Alger Society: Newsboy (July-August, 2010).

Chaney was often covered by the press so this biography incorporates information from dozens of newspaper articles accessed using Newspapers.com. Also useful were reports in the Unitarian denominational publications: The Christian Register, Year-book of the Unitarian Congregational Churches, and The Unitarian. An obituary is found in the Christian Register (May 4, 1922). Useful secondary works include: Earl Wallace Cory’s University of Georgia PhD dissertation, Unitarians and Universalists of the Southeastern United States in the 19th Century (1970); Franklin M. Garrett, Atlanta and its Environs: Chronicle of its People and Events, 1880s-1930s, Vol. 2, (1969); George H. Gibson, “The Unitarian-Universalist Church of Richmond,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, (July, 1966); Harold Francis Williamson, Edward Atkinson: The Biography of an American Liberal, 1827-1905 (1934), and “Dr. Booker Taliaferro Washington: Founder and First President of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute,” on the tuskegee.edu website.

Article by Jim Kelley

Posted February 15, 2019

The author would like to thank Pat Vaughn, archivist of the First Unitarian-Universalist Church of Richmond, Virginia and Jay Kiskell of the North West Unitarian-Universalist Congregation, Atlanta, Georgia for their invaluable assistance with research for this project.