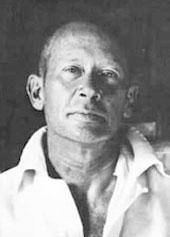

Edward Estlin Cummings (October 14, 1894-September 3, 1962) was one of America’s leading 20th century poets. A prolific poet and painter, Cummings (in his poetry he often ignored the rules of capitalization and has sometimes been referred to as e. e. cummings) expanded the boundaries of poetry through typographic and linguistic experimentation.

Estlin (he was called by his middle name to distinguish him from his father, Edward) was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His father taught sociology at Harvard University before becoming the minister of South Congregational Church (Unitarian) in Boston. His mother, Rebecca, exuded calm and good health and had an artistic bent. Her great-grandfather, Pitt Clarke, was an early Unitarian minister. Her son once commented that her Unitarianism was an integral part of herself. Edward was introduced to Rebecca by his fellow faculty member William James. The Cummings’ large family house was in the shadows of Harvard, just across the street from Professor James.

The family, including a younger sister, was very close. Both parents doted on Estlin, assuming that he would someday be famous. Father Edward was conservative in his theological outlook, but his sermons usually dispensed folksy wisdom of a good-natured sort. Although Estlin frequently and accurately complained that his father did not understand his unique personality, both parents were always loving and financially supportive. Estlin proved to be a self-absorbed individual with an independent outlook and considerable courage.

By the time he was four, Estlin was drawing animals, such as elephants, with hints of perspective. Freehand sketching became a lifetime habit. His father purchased a large farm in New Hampshire called Joy Farm, and father and son would roam the acreage with their bull terrier. The farm was used for a summer retreat throughout Cummings’s life. He enjoyed cutting wood, long walks, and bicycle tours. Other than rowing, he had no interest in team sports. His father was tall, rugged, and strong while Estlin was short and somewhat delicate.

After an unsuccessful stint in private school, Cummings’s father switched him to the Agassiz school, of which Maria Baldwin was the head. Here he displayed a talent for memorizing the poems of Longfellow and Emerson and, before his teens, wrote some simple, two-or-four-line poems. In high school he studied Greek and developed an interest in history and languages, but found philosophy and logic unappealing. Although he remained outwardly obedient to his parents—serving as a church usher—at school he developed a rebellious side.

Entering Harvard in 1911, Cummings took college studies seriously, developing a solid knowledge of Greek and English classics. His poems often appeared in the Harvard Monthly and occasionally in the Harvard Advocate. After living at home for three years, he roomed on campus his senior year. Reveling in new-found freedom, he developed his artistic interests on trips to New York City, where he experienced the new arts and explored earthly pleasures. In 1915, graduating magna cum laude, he gave the commencement address on “the New Art” of Matisse, Duchamp, Stravinsky, and Gertrude Stein.

At Harvard’s graduate school, Cummings spent a great deal of time with the Harvard Poetry Society, where he heard Amy Lowell and Robert Frost. At that time, the Imagist poets Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) were championing concise images and free verse and claiming that meter and rhyme were outdated. Members of this group found resonance with such modern artists as Picasso, Gris, and Duchamp.

Cummings said that he was particularly affected by Pound’s poem, The Return, which lacked meter and took liberties with word spacing. This encouraged him to experiment with spacing and typography, something which was facilitated by a typewriter. An avoidance of capital letters and creative placement of punctuation soon became his trademarks. His experimental poetry took many forms, some amusing, some satirical, some beautiful, some profound, and some which did not make much sense. Even his supportive friend, Williams Carlos Williams, thought this one about a cat almost unintelligible:

(im)c-a-t(mo)

b,i;l;e

FallleA

ps!fl ... (etc.)

To many this looked like the effort of a dilettante. Others discerned a dedicated artist striving for fresh means of expression with which to replace worn out prosody.

During his years in graduate school Cummings made several lifelong friends, including John Dos Passos, who subsequently wrote kaleidoscopic novels on social themes; Gilbert Seldes, who became a writer and critic; and J. Sibley Watson, who would prove to be both a good friend and a financial supporter. Most important was Scholfield Thayer. Wealthy and cultured, Thayer was a great admirer and generous patron of Cummings. In 1919 Watson and Thayer purchased the foundering liberal magazine Dial (no relation to Margaret Fuller‘s magazine) and reoriented it to feature emerging poets and artists. In Watson and Thayer’s new Dial, Cummings would find a steady outlet for his poems and drawings.

After entering Harvard, Cummings’s attendance at church and at his parents’ home for Sunday meals dropped off. This was partly because of other commitments and partly because he had disagreements with his father over his night life. One thing they agreed on was that neither wanted any part of the approaching World War. His father was strongly isolationist. The calendar for the South Church designated 1915 as the “Year of the Peacemaker.” Cummings cared not at all about world wars.

After obtaining his M.A. in 1916, Cummings moved to New York City where he got a job writing business letters at a publishing company. He quit after three months. This was the last time he held a job. Anticipating conscription, Cummings joined the Harjes-Norton American Ambulance Corps and departed for France in the spring of 1917. Because of a bureaucratic mix-up, Cummings and fellow Bostonian, William Slater Brown, enjoyed a month of freedom in Paris before they were assigned to ambulance duty. Cummings fell in love with the city.

After French censors read Brown’s letters home, expressing misgivings about the Allied cause, Brown and Cummings, who refused to incriminate Brown, were both detained. Imprisoned at La Ferté Macé, they were allowed to read books, exercise, make purchases, and write letters home. This state of affairs lasted for three months until Cummings’s father wrote to President Wilson, who had a State Department official secure their release. Back in New York City, Cummings was inducted into the army. When the war ended a few months later, he was discharged. With his father’s encouragement, he vented his feelings about war in a highly fictionalized history entitled The Enormous Room, 1922.

In New York, Cummings met the beautiful and exuberant Elaine Orr. His friend and patron Scholfield Thayer had married Elaine and then lost interest in her. With Thayer’s assent, Cummings moved into Elaine’s life. Their daughter, Nancy, was Cummings’s only child. They married in 1924, after she divorced Thayer, only to divorce themselves a short time later. In deep depression afterwards, Cummings found solace in prayer and work. He was drawn to women, but domestic life held little appeal. His preoccupation with the concrete, physical side of relationships is indicated in the title of his first published book of poetry, Tulips and Chimneys, 1923.

Cummings’s second marriage, in 1929, was even more ill-advised than the first. His new wife, Anne Barton, was divorced and had a four-year-old girl. She was always ready to party. If Cummings could not break loose for drink and dance, she found others who would. In 1932 they obtained a Mexican divorce.

Cummings was never enamored of the moneyed class or celebrity or authority. In 1923 he moved to Greenwich Village, which he would call home for the rest of his life. He had a somber side that craved privacy and what he called an “after breakfast” side that enjoyed running with the crowd. He never ran after the crowd. He could spend days isolated with his work, yet he loved travel. In the twenties Cummings made several trips to Europe and there met with Ezra Pound, Hart Crane, Ford Maddox Ford, Archibald MacLeish, and others. During visits to France, Spain, Tunisia, Mexico, Russia and Italy he enjoyed visiting the museums, attending concerts, viewing stage shows, or just watching the passing parade.

In 1922, when South Church voted to merge with the more prestigious First Church, Edward Cummings, who was sixty-four years old, was asked to retire. A hard blow at first, the retirement brought father and son together and inspired a family pleasure trip to Europe. In 1926, when the family car collided with a train, Dr. Cummings died. Mrs. Cummings survived, but was seriously injured.

Despite his personal trials, the twenties was the time of Cummings greatest productivity. He wrote, and was involved in the production of, the avant garde autobiographical play with the (not unsurprisingly eccentric) title of Him, 1927. Unlike most of his friends, Cummings was a political conservative. His friends genuinely admired his unusual take on the arts, but thought him an elitist. In the introduction to his 1937 collection he wrote: “The poems to come are for you and for me and are not for mostpeople—it’s no use trying to pretend that mostpeople and ourselves are alike . . . Life, for mostpeople, simply isn’t.” Edmund Wilson, a good friend, praised his lyric gifts and enjoyed conversing with him, but said he did not really understand him.

In the thirties he published a book entitled (i.e. no title). It became a collector’s item. He wrote Eimi, 1933, based on his travels during a six-week 1931 visit to Soviet Russia. In 1932, he met Marion Morehouse, a professional model who had her own outside career and found it easy to adapt to Cummings’s lifestyle. They were intimate friends from that time forward. He began to obtain public recognition after his Collected Poems, 1938, reached a wide audience. His poetry covered many subjects, but he was particularly taken with physical love and the miracle of life. He wrote several poems praising God for the rivers, trees, and animals: lions and tigers and especially the elephants.

As readers and critics became more accustomed to Cummings’s typographical explorations, he was accepted and became successful as a poet. In his next books of poetry, 50 Poems, 1940, and 1 x 1, 1944, readers hear echoes of familiar phrases, reversed or turned on end; witness nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs being freely interchanged; and are challenged by creative punctuation, line breaks, and phrasing to perceive everyday ideas in a new light. The following lines, from the book 50 Poems, illustrate some of these techniques:

love is the every only god who spoke this earth so glad and big even a thing all small and sad man,may his mighty fortress dig for love beginning means return seas who could sing so deep and strong one queerying wave will whitely yearn from each last shore and home come young so truly perfectly the skies by merciful love whispered were, completes its brightness with your eyes any illimitable star

Cummings was not nearly as successful in other arts as he was with poetry. His 1935 ballet, Tom, based on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and commissioned by Lincoln Kirsten for the American Ballet Theatre, was never performed. In 1945 and 1948 he had gallery exhibitions of his watercolors and oil paintings. Reunited with his grown daughter Nancy in 1946, Cummings wrote a joyful play celebrating the power of love, Santa Claus, 1946, that met with modest success.

Cummings was awarded the Academy of American Poets fellowship, 1950; he received a Guggenheim fellowship, 1951-52; and he was the Charles Eliot Norton Lecturer at Harvard, 1953. The popularity of the Norton Lectures led him to undertake several public reading tours. He won the Bollingen Prize for poetry, 1958, and received a grant from the Ford Foundation, 1959. All the while he continued to produce books of poetry, some with eccentric typography and others with a unique lyrical quality that inspired compositions by Aaron Copland and other composers. Charles Norman, in his biography of Cummings, says, “His place seems secure by this simple criterion: almost half a century after the memorable Tulips and Chimneys, his first volume of verse, the mere mention of his name can bring entire poems to mind. It applies to all who are truly creative: an artist lives by his works of art, a poet by his poems.”

E. E. Cummings died after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage at Joy Farm. Dana McLean Greeley, President of the Unitarian Universalist Association, led the funeral service, at the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston. A few years later, Cummings’ companion, Marion, was buried beside him with the marker, Marion Morehouse Cummings, 1906-1969.

Sources

Many of Cummings letters, papers, and artworks are in private hands or held by the E. E. Cummings Trust. Other letters, drawings and clippings are in the E. E. Cummings papers at Houghton Library, Harvard. Cummings’ poetry publications not mentioned above, include & (1925), XLI Poems (1925), Is 5 (1926), ViVa (1931), No Thanks (1935), Xaipe (1950), and 95 Poems (1958). Two posthumous collections were published: 73 Poems (1963) and Etcetera (1983). He also published a book of artwork, CIOPW (1931), the title an acronym for Charcoal, Ink, Oil, Pencil, and Watercolor. Complete Poems, 1904-1962 (1981) was carefully assembled and typeset by editor George James Firmage. An excellent collection of Cummings letters is, Selected Letters of E. E. Cummings (1969), edited by F. W. Dupree and George Stade. The Norton Lectures at Harvard were published as i: six nonlectures (1953). Sound recordings are available including E. E. Cummings Reads His Collected Poetry, 1920-1940; E. E. Cummings Reads His Collected Poetry, 1943-1958; E. E. Cummings Reading Him; and i: six nonlectures.

E. E. Cummings: A Biography (2004) by Christopher Sawyer-Laucanno is the standard biography. Among others are Dreams in the Mirror (1980), by Richard S. Kennedy, and The Magic Maker (1958), a biography by Charles Norman approved by Cummings. Norman Friedman’s E. E. Cummings: The Art of His Poetry (1960) offers important critical scholarship. Miscellany (1966) by George Firmage collects a wide variety of pieces from magazines and other sources.

Article by Jerry Frazee

Posted December 12, 2006