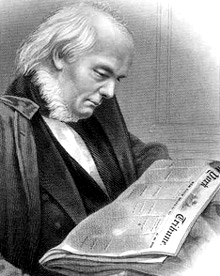

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811-November 29, 1872), Universalist journalist, reformer, and politician, is best known as the longtime, innovative publisher and editor of the New York Tribune. In 1872 he campaigned unsuccessfully for the United States presidency as the candidate of the Liberal Republicans and Democrats, running against incumbent Republican Ulysses S. Grant.

Horace was born in Amherst, New Hampshire, the third child of Zaccheus Greeley, a farmer and day-laborer, and Mary Woodburn. His family moved often, and he was erratically home-schooled until the age of 14. A voracious reader, he was largely self-educated. Although he had never heard of Universalism, through reflection and Bible-reading, he early adopted a Restorationist theology. “Upon re-reading that book in the light of my new convictions, I found therein abundant proof of their correctness,” he later wrote. He saw the scriptures as “so happily blending inexorable punishment for every offense with unfailing pity and ultimate forgiveness for the chastened transgressor.”

After serving as a printer’s apprentice to Amos Bliss, editor of the Northern Spectator, a newspaper in East Poultney, Vermont, and working as a printer on the Erie Gazette in Erie, Pennsylvania, in 1831 he went to New York City to seek his fortune as an editor. Three years later, having worked as a printer for the Evening Post and several other newspapers, he had accumulated enough capital to launch a weekly literary and news journal, the New Yorker, and, in 1840, a Whig campaign weekly, the Log Cabin.

Greeley was introduced to Universalism, first by reading periodicals, and then by hearing a sermon preached around 1830 in Buffalo, New York. In 1831, soon after coming to New York City, he visited, and quickly joined, Thomas Jefferson Sawyer‘s Universalist church on Orchard Street. “Horace Greeley was generally present [at weekly Bible class],” Sawyer recalled, “and entered with great interest into the discussions to which our lessons gave rise. He soon distinguished himself by the quickness of his apprehension, the pertinence of his observations and inquiries, and by the general grasp of his mind upon every topic that came before us.”

In 1836 Greeley married school teacher Mary Youngs Cheney, with whom he shared a passion for poetry and the vegetarian dietary reforms of Dr. Sylvester Graham. Horace’s home life proved comfortless. The Greeleys had seven children, only two of whom, Gabrielle and Ida, lived to adulthood. Mary did not give him the kind of love he had hoped for, had frequent nervous ailments, and neglected the household. Calling their country home outside New York City, “Castle Doleful,” he slept most nights in lodgings close to work.

During their early married life the Greeleys often stayed with the Sawyers. Rev. Sawyer’s wife Caroline had been a frequent contributor to Greeley’s New Yorker and in 1841 in the New Yorker he had just praised her first book as “the gentle teachings of an earnest and holy spirit.” Greeley discussed plans for a new daily newspaper, the New York Tribune, at the Sawyers’ dinner table. When he handed Caroline the first issue of the paper, he told her, “It shall be a power in the land!”

In 1841 Greeley founded the New York Tribune, which he edited and operated the rest of his life. The New Yorker and the Log Cabin were soon absorbed into the Tribune to become a weekly edition for out-of-town subscribers. Over the next two decades circulation rose to more than a quarter of a million, and the Tribune became the most influential newspaper in the country. To customary news reports, Greeley added editorials and commentary on social and political issues. He hired some of the best newspaper men and a few literary luminaries like Margaret Fuller, George Ripley, and Richard Hildreth.

Margaret Fuller wrote featured literary reviews and commentary on social issues, lived in Greeley’s household, 1844-45, and later acted as a European correspondent for the Tribune. He taught her to write rapidly and tersely; she competed with Mary Greeley for the affection of the Greeleys’ infant son, Arthur, and lectured Horace on woman’s rights. He was at first skeptical about the practicality of gender equality: “so long as she shall consider it dangerous or unbecoming to walk half a mile alone by night—I cannot see how the ‘Woman’s Rights’ theory is ever to be anything more than a logically defensible abstraction.” Eventually, in part because of Fuller’s influence, his opinion began to shift. In 1850, shortly after Fuller’s death, he gave the First National Woman’s Rights Convention a moderate endorsement in the Tribune. Although he thought the women who demanded equality were misguided, “However unwise or mistaken the demand, it is but the assertion of a natural right, and as such must be conceded.” In 1858 he praised the preaching of feminist Lydia Ann Jenkins in the Orchard Street Universalist pulpit.

In the course of his journalistic career Greeley espoused a wide variety of liberal causes, including the abolition of slavery and capital punishment, communitarianism, socialism, improvement of working conditions, and free-soil homesteading. He was well known as a writer and in demand as a lecturer. One of his assistants, John Russell Young, later wrote, “Greeley labored with the world to better it, to give men moderate wages and wholesome food, and to teach women to earn their living.”

Greeley was famous for promoting western development and emigration. Although he may not have originated the slogan, “Go west, young man, go west,” often attributed to him, he frequently gave that advice in person and in print. “If any young man is about to commence in the world,” he wrote, “with little in his circumstances to prepossess him in favor of one section above another, we say to him publicly and privately, Go to the West; there your capacities are sure to be appreciated and your industry and energy rewarded.”

Greeley had first entered the political arena in 1840, promoting the candidacy of William Henry Harrison. He remained a politician for the rest of his life, promoting first Whig and, later, Republican causes. He helped to organize the Republican Party in 1856 and campaigned for Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Having developed a “thirst for public office” while serving three months in Congress in 1848-49, he ran unsuccessfully for the Senate in 1863, for the House in 1868 and 1870, and the presidency in 1872. Greeley’s political and social views reflected his strongly held religious views. His reforms aimed at creating a society in which men and women would be less inclined toward moral transgressions and more inclined toward actions that “shall ultimately result in universal holiness and consequent happiness.”

A pacifist who believed in the right of states to secede from the United States, in 1861 Greeley nevertheless came to believe that the South had to be resisted with force. He applied public pressure on Lincoln to immediately emancipate the slaves. In an 1862 editorial addressed to the president, “The Prayer of Twenty Millions,” he wrote that he was “sorely disappointed and deeply pained by the policy you seem to be pursuing with regard to the slaves of rebels.” Lincoln answered, “If I could save the Union without freeing any slaves, I would do it—if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it—and if I could do it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.” When Lincoln in 1862 published the Emancipation Proclamation—at a time of his own choosing and not of Greeley’s—Greeley rejoiced: “it is the beginning of the new life of the nation.”

During the 1863 New York draft riots, an anti-Greeley mob nearly succeeded in storming the Tribune building. When weapons were brought into the building to stave off attack, Greeley exclaimed, “Take ’em away! I don’t want to kill anybody!” Discouraged by the progress of the war and conflicted about the use of deadly force, Greeley made several attempts during 1863-64 to bring about peace. Each effort resulted in personal embarrassment when the parties with whom he had been negotiating became known. Throughout the war Greeley alternately castigated and lauded Lincoln, sometimes supported him and at other times undermined his policies. “I do not suppose I have any right to complain,” Lincoln remarked. “Uncle Horace agrees with me pretty often after all; I reckon he is with us at least four days out of seven.”

When Sawyer left the Orchard Street church in 1845, Greeley found the new minister too rationalistic and dropped away, returning only when Sawyer himself returned in 1852. After Sawyer’s second departure in 1861, Greeley remained an active Universalist for the rest of his life. In 1864 he preached a sermon from Edwin H. Chapin‘s pulpit at the Church of the Divine Paternity in New York. As a delegate to the 1870 General Convention in Gloucester, celebrating the centennial of John Murray’s arrival in America, Greeley attempted unsuccessfully to divert funds raised for other purposes to creating a Universalist publishing house.

There were both Transcendentalist and anti-trinitarian elements in Greeley’s Universalism. Among his friends were Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Greeley had a Transcendentalist belief that “an Omniscient Beneficence presides over and directs the entire course of human affairs, leading ever onward and upward to universal purity and bliss, and all evil becomes phenomenal and preparative.” Illustrative of Greeley’s anti-trinitarianism is his assertion in his later years that, along “with the great body of Universalists of our day (who herein differ from the earlier pioneers of our faith), I believe that ‘our God is one Lord’ . . . and I find the relation between the Father and the Saviour of mankind most clearly and fully set forth in that majestic first chapter of Hebrews, which I cannot see how any Trinitarian can ever intently read, without perceiving that its whole tenor and burden are directly at war with his conception of ‘three persons in one God.'” Having recorded his decided belief, he added tolerantly, “I war not upon others’ convictions, but rest satisfied with a simple statement of my own.”

In 1872 Greeley’s life came to a sad and bitter end. During his campaign for the presidency Republicans had ridiculed him for his clothes, shambling gait, and absent-minded manner and portrayed him as a traitor (for his earlier criticisms of President Lincoln), a fool, an ignoramus, and a crank, weak in judgment and nerve. He was pilloried in merciless cartoons by Thomas Nast and others. Grant won the election in a landslide, with Greeley victorious in only six border and Southern states. He described himself as the “worst beaten man who ever ran for high office.” While he was campaigning, his colleague at the Tribune, Whitelaw Reid, stripped him of his editorial powers. Just before the election his wife died. The combined effect of these disasters led to a complete physical and mental breakdown. He died soon afterwards.

Death

Greeley’s funeral, led by Chapin at the Church of the Divine Paternity on December 4th, was attended by many notables, including the president, vice president, members of the cabinet, the mayor, and three governors. On that occasion, and since that time, Greeley has been remembered as his country’s greatest newspaper editor, an outstanding popular educator, and a notable champion of the downtrodden and dispossessed.

Sources

There are Greeley papers at the Library of Congress and at the New York Public Library. Greeley was a prolific writer: besides his newspaper articles he wrote a number of books, including Hints Toward Reforms (1850), Glances at Europe (1851), A History of the Struggle for Slavery Extension or Restriction in the United States (1856), An Overland Journey, from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859 (1860), The American Conflict, 2 vols. (1864 and 1866), and What I Know of Farming (1871). Along with Thomas J. Sawyer and Octavius Brooks Frothingham he contributed to The religious aspects of the age, with a glance at the church of the present and the church of the future, being addresses delivered at the anniversary of the Young Men’s Christian Union of New York (1858). For a detailed bibliography consult Suzanne Schulze, Horace Greeley: A Bio-Bibliography (1992).

Greeley wrote a great autobiography, Reflections of a Busy Life (1873, reissued 1971). There have been numerous biographies. Among these are James Parton, The Life of Horace Greeley (1855); L. D. Ingersoll, The Life of Horace Greeley (1873); William Harlan Hale, Horace Greeley: Voice of the People (1950); and Erik S. Lunde, Horace Greeley (1981). There are biographical entries in standard reference works: by Allan Nevins in Dictionary of American Biography (1931) and by Eric S. Lunde in American National Biography (1999). For material on Greeley’s relations with Universalists and Transcendentalists see Russell Miller, The Larger Hope, 2 vols. (1979 and 1985); Charles A. Howe, “Under Orders from No Man: Universalist Women Ministers Before the Civil War” and “Not Hell, But Hope,” The John Murray Distinguished Lectures, 1987-1991, Murray Grove Association (1991); Richard Eddy, The Life of Thomas J. Sawyer and of Caroline M. Sawyer (1900); Lindsay Swift, Brook Farm (1961); Perry Miller, The Raven and the Whale (1956); Henry Seidel Canby, Thoreau (1958); and Laurie James, Men, Women, and Margaret Fuller (1990).

Article by Charles A. Howe

Posted March 4, 2006