Homer Alexander Jack (May 19, 1916-August 5, 1993) was a Unitarian Universalist minister and early activist for peace, disarmament, racial equality and social justice. An accomplished writer and speaker, he organized and led a number of civil rights, disarmament, and peace organizations.

Jack grew up in Rochester, New York where he attended public schools. His father Alexander was a successful graphic designer, newspaper artist, and co-owner of the Lincoln Photo Engraving Company. His mother, Cecelia (Davis) Jack was a homemaker. Both were non-practicing Jews but ardent socialists, activists, and free-thinkers. Jack was introduced to Unitarianism in junior high school when he befriended George and Esther Williams, children of David Rhys Williams, minister of Rochester’s First Unitarian Church.

Attending Burroughs-Audubon nature club lectures and taking Saturday nature hikes with his parents, piqued Homer Jack’s interest in botany and geology. As a high school student he spent summers doing field work at the Allegany School of Natural History in New York and at the University of Michigan biological station. Jack entered Cornell University in 1933 to study botany. To broaden his education, he spent his junior year at Earlham College, a Quaker school in Richmond, Indiana. Returning to Cornell he moved off campus to room with international students, making life-long friendships with Asians, Africans, and Europeans. Jack received his bachelor’s degree from Cornell in 1936 and his M.S. in science and zoology the following year.

Work was scarce in 1937 so he took a job teaching college English in Athens, Greece. At the end of the school year Jack resigned his position and toured Europe for six months visiting biological research stations to gather more data for his doctoral thesis.

Jack visited 79 research stations in 18 countries in Europe, Africa, and North America, 1937-1941; and he gathered survey data by mail from dozens of other stations. In 1940 he received his Ph.D. from Cornell, but his thesis, Biological Field Stations of the World: A comparative and descriptive study, 1945, wasn’t published until after the war. He also wrote magazine articles for Science and The American Biology Teacher.

As he neared the end of his doctoral studies, Jack’s flirtation with Unitarianism and his friendship for Esther Williams grew serious. Esther had graduated from Oberlin College and was working as a social case worker in Cleveland, Ohio. They exchanged letters and started dating regularly. In 1939 they were engaged and that November they were married by her father at First Unitarian church in Rochester, New York.

Jack had expressed interest in Unitarianism and the ministry as early as 1935 but he didn’t act upon it until the summer of 1940 when he enrolled at Meadville Theological School in Chicago. He found ministerial life exhilarating and challenging. His commitment to social justice soon dominated his activities: he wrote his thesis on “Denominational Social Action.” Jack insisted that “there is more potential for social change coming from the liberal pulpit than most realize.”

With other “radical” students, Jack attempted to unionize the blacks who worked for Meadville, picketed the British Consulate on behalf of Gandhi’s “Quit India Day” protest, and held a chapel service in support of a Chinese-American who refused to be drafted. In 1942 he began attending meetings of the Chicago branch of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), a pacifist Quaker organization. Here he met and worked with Bayard Rustin, Quaker; George Houser, follower of Henry David Thoreau and nonviolent resistance; and James Farmer, a disciple of Mohandas Gandhi.

College activism and tight finances, coupled with an internship at the Universalist Church of Litchfield, Illinois put stresses on his marriage that led to separation and divorce. Looking for a church, Jack declared he was “a socialist and pacifist” but “hoped that these philosophies would, if anything, make me more tolerant and understanding.” He was called to the Unitarian Church of Lawrence, Kansas in 1943.

Lawrence, like most American cities at that time, was racially divided. It addition it was anti-labor and anti-Roosevelt. Finding the Lawrence Unitarian Church a “mess”, small, aging, and heavily in debt, Jack attempted to revive it. His most successful effort was the Saturday Evening Club, an “inter-racial, inter-denominational, college-age” group. In the pulpit, Jack questioned the Second World War, preaching a Thanksgiving sermon entitled: “Dare We Be Thankful Today?”

In 1944 Homer reconciled with Esther and they remarried. Homer’s son, Alexander was born in 1945 followed by a daughter, Lucy, two years later.

Graduating from Meadville with a B.D. in 1944, Jack’s thoughts were on World War II, pacifism, the draft, and supporting his family. He was secretary of the Unitarian Pacifist Fellowship consisting of fifty ministers and 150 laymen and he planned to become a conscientious objector if drafted.

Working as Executive Secretary of the Chicago Council Against Racial and Religious Discrimination (CCARRD) during his summer vacation in 1944, Jack realized he’d found the challenge he was seeking. He didn’t return to Kansas in the fall even though it meant the loss of his ministerial deferment. The Lawrence church closed the next year. Jack served as CCARRD Executive Secretary, 1944-48, latter describing it as his “first important position.” His job was to build “a coalition of organizations” that would work together on racial and religious matters.

Focusing on discrimination against blacks, his goals for CCARRD were to develop methods to influence city government, to develop effective intervention tactics that would reduce racial tensions, and to carefully document the Council’s work. To accomplish these goals he established the newsletter Against Discrimination. He spoke frequently and wrote articles and reviews. The Council supported legislation for fair employment practices, fought racially restrictive covenants keeping blacks from buying property, intervened in potential riot situations, and helped in the founding of nonracial Roosevelt College. Jack worked with a cross section of leaders including Preston Bradley, the pastor of All Soul’s Unitarian Church in Chicago, and Thurgood Marshall, legal counsel for the NAACP. Nationally, he served as president of the Unitarian Fellowship for Social Justice, 1947-49.

In 1946 the Supreme Court declared segregated seating on interstate buses and trains unconstitutional. A year later the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which Jack had helped found, organized a “Journey of Reconciliation” to test compliance with that decision in border states. Homer Jack was one of 16 riders, half black and half white, who rode together, sitting wherever they pleased, explicitly breaking local Jim Crow laws. Black and white riders were arrested and jailed in a number of cities with many serving time on chain gangs. The “Journey of Reconciliation,” widely reported in the black press, became the model for later non-violent “freedom rides.”

In the autumn of 1948, feeling “burned out,” Jack accepted a parish ministry post at the Unitarian Church of Evanston, Illinois. Although Evanston was very conservative, Jack and his church pushed for social change and desegregation. The congregation prospered during his eleven years there; membership rose from 175 to about 600, church attendance from 100 to 355. A new and larger church building was finished in 1958. His sermons, often controversial, were widely mimeographed and reprinted: the Christian Register published one of the best known, “Sunday at 11: The Segregation Hour.” In his autobiography Jack called his eleven years in Evanston, “The Golden Years.”

During his Evanston ministry Jack took his first round-the-world journey, 1955; visited Albert Schweitzer twice; became acquainted with the struggles for independence developing in Asia and Africa; spoke in opposition to nuclear testing; made the first of about 20 visits to India; and participated in the Third World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs and For Disarmament held in Japan, 1956. Two books, The Wit and Wisdom of Gandhi, 1951, and The Gandhi Reader, 1956, grew out of his research in South Africa and India.

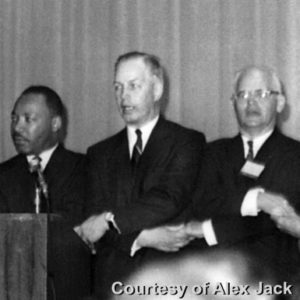

In 1956 he went to Alabama to support the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He met Martin Luther King, Jr. and was invited to preach to his congregation. King also asked Jack to give the keynote address at a week-long conference, the Institute on Nonviolence and Social Change. “Homer Jack is certainly one of the most dedicated persons that I have ever met.” King said in 1959, “He combines the fact-finding mind of a social scientist with the great insights of a religious prophet.”

Wanting to return to social activism, Jack resigned his pulpit in 1959 and moved to New York City. In his farewell to the congregation he said “I am no longer a doctrinaire humanist. Indeed, I now believe that I would have little difficulty becoming a practicing Quaker or Congregationalist or Zen Buddhist.” He said we “should try to be a church of the people, not a church of the best people.” In Manhattan he co-founded and served as Associate Director of the American Committee of Africa, 1959-60. This organization worked to help achieve independence for the European colonies in Africa.

In 1960 he accepted the call to serve as Executive Director of the National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE), a group he had helped start in 1957. The purpose of SANE Jack wrote, was “to lead American public opinion in favor of an inspected ban on nuclear weapons tests and substantial steps toward disarmament.” One of his successes was getting Dr. Benjamin Spock, author of the popular Baby and Child Care book, as a spokesperson and board member. Jack stepped down in 1964 but continued working with SANE as a board member, 1964-84.

Dana McLean Greeley, president of the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA), invited Jack to be his adviser on social justice questions in 1964. Jack agreed and was appointed director of a new Department of Social Responsibility. Over the next five years Homer Jack played a major role in the denomination’s positive response to the 1960s civil rights, human justice and peace crises.

Jack mobilized the UUA staff, churches, ministers and congregations to the challenge for good inherent in the civil disobedience movement, the struggle by blacks to end segregation, and the need to end the destructive Vietnam War. In 1965 he led more than 100 UU ministers in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. Jack believed that “it’s not enough to write or preach about brotherhood and peace. One must try however one can to jump into the fray.”

In 1967, as director of the UUA Department of Social Responsibilty, Jack called for an Emergency Conference on Unitarian Universalist Response to the Black Rebellion. But, the conference went in a direction that Jack didn’t forsee; instead of exploring possible responses to the Black Power struggle across the nation, the conference revealed the racial dissension within the Unitarian Universalist Association. The militant Black Caucus along with moderate whites accused Unitarian Universalists and the UUA of racism. They issued non-negotiable demands including one for funding. The result was a controversy in which dialogue and calm understanding played no part.*

Homer Jack tried to steer a middle course in this situation and as a result was treated harshly and unfairly by many individuals. Dana Greeley offered this assessment: “The Black Caucus officers were very rude to Homer Jack, who had promoted their interests as well as anybody, but who maintained his independent judgment and was perhaps actually only 95 [percent] supportive of them.” In his autobiography Jack called the 1968 confrontation with black UUs one of the two most stressful situations of his professional career.

At the 1969 UUA General Assembly, Robert N. West was elected president. Severe budget problems forced him to cut the Association’s work drastically. One of the departments eliminated was that of Social Responsibility. Homer Jack lost his position. Jack and Raymond C. Hopkins, the UUA Executive Vice-President at the time, always considered that he had been fired rather than made redundant by the new president.

In 1970, Jack was asked to be Secretary-General of the World Conference on Religion and Peace (WCRP). He had helped organize the group working with Dana McLean Greeley, Rabbi Maurice N. Eisendrath and religious leaders from Japan, India, and Germany. Jack accepted and served until 1983 when he was made Secretary-General Emeritus.

As Secretary-General, Jack’s major responsibility was organizing conferences. Working from the WCRP office near the United Nations in New York City he traveled the world, delivering addresses, overseeing projects, and meeting with people who shared the WCRP’s outlook. The first WCRP world gathering was held in 1970 in Japan and was attended by four hundred religious leaders from 39 countries. The participants discussed the Vietnam War, racial harmony, and methods to achieve disarmament. Other world conferences while he was Secretary-General followed in Leuvan, Belgium, Princeton, New Jersey, Sydney, Australia, and Nairobi, Kenya.

When Homer Jack moved to New York City to lead the WCRP, Esther and the children stayed in Boston. They divorced a second time. In 1972 he married Ingeborg Kind, a German Quaker.

Jack returned to parish ministry two more times; serving the Unitarian Fellowship of Northern Westchester, Mt. Kisco, New York, 1973-74; and the Lake Shore Unitarian Universalist Society, Winnetka, Illinois, 1984-87.

Although he “officially” retired in 1987, Jack continued to travel, lecture and write articles which were published widely. Indeed, between 1947 and 1991 he wrote 70 articles for the leading American Protestant journal, the Christian Century. In 1983 he issued Disarm or Die and in 1993 WCRP: A History of the World Conference on Religion and Peace. His autobiography, Homer’s Odyssey: My Quest for Peace and Justice, left unfinished at his death, was completed by his son and published in 1996.

In 1982 Jack received The Pomerance Award from the Committee on Disarmament, a nongovernmental organization working with the United Nations, which he had founded in 1973. In 1984 he received the second Niwano Peace Prize for distinguished achievement promoting world peace. Earlier, Meadville/Lombard Theological School awarded him an honorary D.D. (1972), and in 1989 the UUA gave him the Holmes/Weatherly Award for distinguished social action service.

Death

Jack died at home from pancreatic cancer in 1993. The Rev. Judith Downing conducted a memorial service at the Unitarian Church, Media, Pennsylvania. Services were also held at the Unitarian Church of Evanston and the World Church Center (across from the United Nations) in New York City. Homer Jack’s ashes were scattered in a holly grove at Swarthmore College while a passage about the scattering of Gandhi’s ashes was read.

Sources

The Homer Alexander Jack papers (1930-1995) along with conference proceedings, committee files and documents of organizations Jack was affiliated with are in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. Materials relating to positions he held with the AUA and the UUA, his UUA Ministerial file, a small biographical file, and the UUA archives of the Department of Social Responsibility are housed at the Andover Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. For biographical data consult Jack’s Odyssey: My Quest for Peace and Justice (1996) and A Bibliography of the Writings of Homer A. Jack (1991).

Also helpful are Alex Jack, “Homer A. Jack: Social Activist (1916-1993),” in Notable American Unitarians 1936-1961 (2007); Dana McLean Greeley, 25 Beacon Street and Other Recollections (1971); Victor H. Carpenter, Long Challenge: the Empowerment Controversy (1967-1977) (2003); Warren R. Ross, The Premise and the Promise The Story of the Unitarian Universalist Association (2001); and Alice Blair Wesley, Odysseys: the Lives of Sixteen Unitarian Universalist Ministers (1992). Obituaries are in the New York Times (August 8, 1993), the Boston Globe (August 9, 1993), the Christian Century (October 27, 1993), and the UUA Directory 1995-96.

* For more on this controversy read In Their Own Words a Starr King School for the Ministry report. Also see Mark Morrison Reed, The Selma Awakening How the Civil Rights Movement Tested and Changed Unitarian Universalism, (2014).

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted January 25, 2011