Charles Rhind Joy (December 5, 1885- September 26, 1978) was a Unitarian minister, American Unitarian Association official, and an international humanitarian worker affiliated with the Unitarian Service Committee, Save the Children Federation, and CARE. He wrote popular articles for magazines and authored numerous books. He is widely known for his children’s books and his translations of Albert Schweitzer’s works.

Charles Joy was the third of seven children born to Arabella Sophia Parke and Robert S. Joy. Born in Canada, his father had emigrated to Boston where he worked as a decorator for a flags and bunting business. Named George Rhind Joy for two of his mother’s uncles, George Bishop and John Rhind, his parents later changed his name to Charles, after a family disagreement with Uncle Georg

Young Joy grew up in Roxbury and attended Hugh O’Brien Grammar School, although the family relocated to the Boston neighborhood of Dorchester Center in 1901, he was allowed to attend Roxbury High School. In Dorchester, the family was active in the Stanton Avenue Methodist Church, as was the family of his future wife, Lucy Alice Wanzer.

After graduating from high school in 1904, Joy entered Harvard College where he majored in English literature and modern languages, becoming proficient in French and German. Four years later he received his A. B. with distinction in English. That autumn he entered Harvard Divinity School for, as he wrote in his twenty-fifth Harvard Class report, “It was my ambition to combine theology and literature in one career.”

At that time the Harvard Divinity School and Andover Theological Seminary, were separate schools that cooperated in the training of ministers. Students could take courses in either school and had access to the combined libraries. It also permitted students, if they wished, to receive an Andover and a Harvard degree when they graduated. During this time Joy became interested in Unitarianism. His strongest influence was the divinity school Dean, William Wallace Fenn, a prominent Unitarian theologian and educator. When Joy graduated in June 1911, receiving a dual S.T.B. from Harvard and Andover, it was as a Unitarian.

The day after commencement, Joy and his youthful family friend, Lucy Alice Wanzer, were married in the Chapel of the Divinity School by Dean William Fenn. They had four children: Alice, Lucy, Robert, and Nancy.

That summer Joy preached at the Unitarian Church in Brewster, Massachusetts before accepting a position as acting minister at First Parish in Portland, Maine. Portland was, he wrote, “an important church, the largest and strongest of the Unitarian fellowships in Maine. It was only the unfortunately prolonged illness of the minister of the church that opened the doors of this parish to an inexperienced young chap like myself.” He became its settled minister when they ordained him in January 1913. His friend, Dean William Fenn, gave the prayer and the charge.

While at Portland Joy purchased a farmhouse, barn, and 101 acres of land in nearby Gray. The lot included three lakefront properties on Little Sebago Lake. It would become a beloved summer retreat for several generations of the Joy family.

Things went well for the minister and the congregation at First Parish until America entered the First World War in 1917. When Joy told the congregation that he was a pacifist and that the war was “unrighteous,” he was burned in effigy outside of the church. Shortly thereafter he learned that the congregation now found his preaching “unacceptable.” So he resigned, joined the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), and became a part of the YMCA humanitarian and welfare service for soldiers in Europe. While he was overseas, his family lived with his wife’s parents in Dorchester and then with his parents in Watertown, Massachusetts.

His fluency in French and German made him an extremely useful employee. At first he assisted French soldiers in their training camps near the front lines and American soldiers with the Forty-Second Infantry (Rainbow) Division. Later he was the YMCA Secretary of the Rouen Division and then its Religion Director for parts of northern France and Belgium. For his service, the French government awarded him the médaille commémorative de la Grand Guerre.

Joy returned home in 1919 and was soon called to the pulpit at Unity Church in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Its first minister had been his college mentor and friend, Dean William Fenn. Joy’s service was brief, however, for in January 1922 he received a unanimous call to the First Parish in Dedham, Massachusetts. While there he also served as the Literary Editor (1923-25) for the leading Unitarian magazine, The Christian Register, and as the Secretary of the national Unitarian Ministerial Union. In addition, he served as Director, 1929-1941, and First Vice-President, 1925-1938, of the Unitarian Isles of Shoals summer conference center just off shore at Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

In 1927, he moved to the Unitarian Church in Lowell, Massachusetts. One of his objectives for this ministry was to spur a closer union between Unitarians and Universalists. Once again though, his ministry was short lived. Within two years, Louis Craig Cornish, the President of the American Unitarian Association (AUA) appointed him as Administrative Vice-President. In this position, he oversaw the needs of congregations and, where necessary, recommended mergers and consolidations with neighboring churches. When Joy assumed his position with the AUA in 1929, he purchased a home in Newton Highlands, Massachusetts. It became the Joy family’s permanent residence for the next several decades.

Joy also served as the adult advisor for the denomination’s youth organization, the Young Peoples Religious Union, 1932-37; was on the Board of Trustees of The Christian Register, 1931-37; edited the Wayside Pulpit series; and was the Secretary and Executive Officer of the Free Church Fellowship (FCF), 1935-37. The purpose of the FCF was not to create a single denomination, but to allow the Unitarians and Universalists, and perhaps other religious groups, to unite into “a larger fellowship” while still retaining their separate identities. Joy saw the Free Church movement as the first step toward his overall goal of uniting the two declining denominations.

In April 1933 the Pacific Unitarian School for the Ministry in Berkeley, California (later the Starr King School for the Ministry) gave Joy the honorary degree of Doctor of Sacred Theology.

In 1937, as Cornish’s term as AUA President neared its conclusion, the board of directors unanimously nominated Frederick May Eliot to succeed him. Some Unitarians, however, fearing Eliot’s views were too “humanistic,” nominated Charles Joy by petition. Joy was an unquestioned liberal Christian. Committees supporting both men were formed, which many feared might result in a bitter election. In the interest of denominational harmony, Joy withdrew his candidacy declaring: “If in anyway I have misrepresented Dr. Eliot, I am sincerely sorry. I hope that his administration may be happy, fruitful, and blessed of God.” Joy now focused his life on serving people in need around the world along with editing, translating, and writing.

Returning to the ministry, he chose to serve as an interim minister. Between 1938 and 1940, he served the Church of the Messiah in St. Louis, Missouri; the First Parish in Waltham, Massachusetts; the First Unitarian Congregational Church in Cincinnati, Ohio; and the Church of the Disciples in Boston. Concurrently, he completed a concordance of the Bible, a project that he had been working on for many years. It was published in 1940 as Harper’s Topical Concordance compiled by Charles R. Joy. A standard reference tool for ministers, it was reprinted several times.

Between the World Wars, American Unitarians reached out to congregations in Czechoslovakia and Transylvania. Two important links were Charlotte Garrigue Masaryk and Norbert Capek. As early as 1938 the AUA had begun exploring ways to help those endangered by the Third Reich. Robert Dexter and his wife Elisabeth were sent on a four-month long fact-finding tour of Europe to assess what might be done to help refugees, especially Jews, escape from the Nazis. Then in 1939 Waitstill and Martha Sharp, a young Unitarian minister and his wife, spent several months in Prague where they established a relief and emigration program. In 1939 German forces under Adolph Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia.

By May 1940, the AUA had created the Unitarian Service Committee (USC) for the purpose of “investigating opportunities for humanitarian service both in America and abroad.” Robert Dexter, head of the AUA’s Department of Social Relations, was named the first Executive Director. It’s aim was to rescue as many “of Europe’s intellectual, academic, and political leaders” as possible and to meet people’s social and medical needs, as best it could.

In 1940, once the USC was established, the Sharps returned to Europe and opened offices in Lisbon and Marseille. Dexter then asked Charles Joy to work for the USC overseeing the Lisbon office. Joy arrived in mid-September, and with his command of German and French, his administrative skills, and his previous humanitarian experience, he soon proved his worth. Joy ran the Lisbon office frugally using one room for his bedroom, and eating all his meals a la carte. Frugality was also his rule for the refugees. From time to time, he visited the Marseille office from which he often accompanied fleeing refugees to the Spanish border, one of the escape routes out of France. Sometimes he even accompanied them to Lisbon, Portugal.

In 1940, once the USC was established, the Sharps returned to Europe and opened offices in Lisbon and Marseille. Dexter then asked Charles Joy to work for the USC overseeing the Lisbon office. Joy arrived in mid-September, and with his command of German and French, his administrative skills, and his previous humanitarian experience, he soon proved his worth. Joy ran the Lisbon office frugally using one room for his bedroom, and eating all his meals a la carte. Frugality was also his rule for the refugees. From time to time, he visited the Marseille office from which he often accompanied fleeing refugees to the Spanish border, one of the escape routes out of France. Sometimes he even accompanied them to Lisbon, Portugal.

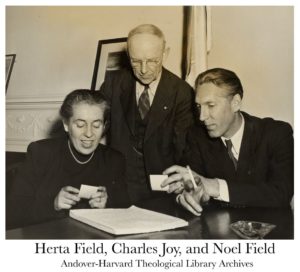

Joy later asked Noel and Herta Field to run the Marseille office and clinic. Their work there and later at the Geneva office was excellent. However, their involvement with Communism made them, for some people, controversial figures. In 1942,

Lotta Hitschmanova, a poor and starving Jewish refugee from Prague was among the refugees treated at the USC clinic in Marseilles. She later emigrated to Canada where she started the Canadian Unitarian Service Committee.

It was while Joy was in Lisbon that he commissioned Hans Deutsch, a refugee on staff, to design a symbol for the Committee. Deutsch drew a flaming chalice, which Joy described as “simple, chaste and distinctive,” adding “the holy oil burning in it is a symbol of helpfulness and sacrifice.” It was adopted as the USC’s official seal in April, 1941.

The primary task of the Lisbon office was to rescue and help refugees relocate to safety; however, over time it also came to provide money, food, clothing and

medicine to people either in Portuguese jails or in hiding. It was demanding, hectic, confusing work and often meant working with other religious groups and charity organizations, plus with double agents, reluctant government officials including American ones, minor functionaries, agents of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), communists, and various shady unscrupulous characters. Nevertheless, the small staff of the Service Committee produced amazingly positive results overall.

Still this did not prevent a serious problem arising in June 1944 between Joy and the Dexters who accusing Joy of “incompetence and dishonesty” and demanded that he be fired. The root of the conflict was different ideas of service held by the Dexters and Joy. When the charges were investigated, they were found “baseless” which led the Dexters to resign and Joy to become Executive Director of the USC operating from Boston, a position he held until 1946.

Ghanda Di Figlia’s 1990 history of the Unitarian Service Committee, Roots and Visions, fairly assesses its work during the war; “The numbers rescued through the USC’s efforts (usually in collaboration with other agencies),” she wrote, “cannot be calculated with total accuracy. Case records and unsubstantiated lists in the archives suggest a figure between 1,000 and 3,000. But the measure of the work, finally, is not in the numbers saved but in the witness of those who served in Europe and of those who supported the work at home.” In 2006, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. arranged with the library of the Harvard Divinity School, which holds the archives of the Service Committee, to have much of the material dealing with the war years digitized. By 2012 this had been accomplished. The project recognized what Joy, the Sharps, the Dexters, and others were able to accomplish “especially for those who were Jewish” when Nazism ruled so much of Europe.

With peace, the Committee’s work shifted from rescue efforts to supplying food, clothing, and medical services; especially to refugees and children. The Committee had opened a Paris office in 1944, which was run effectively by Jo Témpi, a German anti-fascist but also a German Communist. It provided a central location for the European work, which was now only a small part of the expanded programs supported by the Committee. One of the most noteworthy actions authorized by Joy was providing funds in 1946 “the first American organization to do so” to help save Albert Schweitzer’s African hospital. In dire straits it was on the verge of closing.

In June 1946, Francis Henson of the International Rescue and Relief Committee (IRRC) wrote Reinhold Niebuhr telling him that the USC in Europe was dominated by Communists. Niebuhr forwarded the letter to John Haynes Holmes who shared it with Donald Harrington. Harrington shared it with Winscott Tyler, a Unitarian layman. Tyler a freelance sleuth and former FBI agent, followed Jo Témpi “who was in America raising funds for the USC” and discovered that she shared a railroad compartment and a New York hotel room with Charles Joy. Tyler brought his information to the attention of the USC board on behalf of the conservative Committee of Free Unitarians, a Boston based group that opposed Joy’s policies and considered Eliot too “humanistic.” Joy denied being a Communist and he denied having sexual relations with Jo Témpi. After an investigation, the Unitarian Service Committee Board fired Joy but retained Témpi. Frederick May Eliot cast the only vote in Joy’s favor. That vote is still significant: Eliot’s integrity has never been challenged. As a further show of support, Eliot appointed Joy as a consulting editor at Beacon Press. In late October, a few days before mid-term U.S. elections, Unitarian Service Committee board members and Christian Register Editor Stephen Fritchman were called to testify by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Obviously hurt by the board’s decision, Joy never wrote a word about this period of his life. He elected to continue his international work and had no problem securing responsible positions. He served as Associate Director for European Affairs and European Director of the Save the Children Federation, a leading charity working on behalf of children, 1947-1950, and he was employed by CARE (Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere), one of the most important organizations devoted to fighting world poverty, 1950-1955. At CARE he was a National and International Field Representative, 1950-1952; Mission Chief for Korea, attached to the American Army with a rank equivalent to Colonel, 1952-1954; and finally the Executive Consultant For African Affairs, 1954-1955. While his office was in New York City during these years his duties required travel world-wide.

When he reached age seventy, Joy decided to retire and, as he called it, enter the third period of life: He now devoted all his time to lecturing and writing, pursuits that had been secondary up until then. Among the books he wrote was a series on Albert Schweitzer, published by the AUA’s Beacon Press. He considered Schweitzer “one of the truly great men of all time.” Joy – along with Melvin Arnold the Director of Publications for the AUA – visited Schweitzer and his hospital in Lambaréné in 1947. While there Joy, an excellent photographer, took hundreds of photographs which were later published in his books and Life and Time magazines. Schweitzer also gave him permission to translate his various works. During the late 1940s, Joy translated/published eight books about or by Schweitzer. They proved popular, going through several editions. Some are still in print such as Albert Schweitzer: An Anthology (1947) and The Spiritual Life: Selected Writings of Albert Schweitzer (1947).

He wrote another series of books for young people about average children living in various countries around the world. These grew out of his work and travels for CARE. Many were first published by Senior Scholastic Magazine and later by other publishers. Two examples are Young People of West Africa (1961) and Getting to Know Tanzania (1962).

After the death of his wife Lucy in 1962, Joy moved to Albany, New York to live with his daughter Alice. He continued to write and attended, when he could, Albany’s First Unitarian Church. The congregation named their library in his honor. Over the years, he received other honors including three from the Portuguese government for his war work in that country and the Palme Académique (France). He was also made an Officer of the French Academy and a Life Fellow of the International Institute of Arts and Letters.

Charles Joy died September 26, 1978. At his request, his body was donated to science. His funeral service was held at the Albany Church. Later his family erected a memorial gravestone at the local cemetery in Gray, Maine near their beloved summer home.

Ghanda Di Figlia in her Unitarian Service Committee history wrote, “The evidence from his papers and numerous human interest stories suggest a gracious, compassionate man, committed wholeheartedly to the growth of liberal religion and doing all he could to promote the Service Committee as a vehicle for that growth.” The writer of his UUA Directory obituary concurred, “We have had few ministers with as many and varied talents, and none with a more open and loving nature.”

Sources

The Charles R. Joy papers are housed at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts and at the Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library, Syracuse, New York. Andover-Harvard also holds the papers of the American Unitarian Association and the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee. For more information on these collections see the essays by Timothy Driscoll “Documenting an Institutional History: The Unitarian Universalist Archives Project at the Harvard Divinity School,” The Proceedings of the Unitarian Universalist Historical Society (1995), and “Unitarian Universalist Service Committee Archives at the Harvard Divinity School: A Brief History and Collection Guide,” The Journal of Unitarian Universalist History (1998). Joy wrote dozens of books in addition to those mentioned in the text. Search at WorldCat.org for a complete list.

For biographical data see Notable American Unitarians 1938-1961 ( 2007), ed. Herbert E. Vetter; Warren Joy (his nephew), “Dr.Charles R. Joy: 1885-1978” (1985), MSS (available at Andover-Harvard Theological Library); and Mark W. Harris, Historical Dictionary of Unitarian Universalism, (2004). There is a Joy obituary in the UUA Directory (1980), an entry in Who Was Who in America, and articles in the New York Times.

For histories of the Service Committee see James Ford Lewis, “The Unitarian Service Committee,” PhD dissertation, University of California, (1967); Ghanda Di Figlia, Roots and Visions: The First Fifty Years of the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee (1990); Nora Newhart, The Unitarian Service Committee: Under the Direction of Robert C. Dexter, 1938-1944, Honors Thesis, History Department, Clark University (2009); and Susan Elisabeth Subak, Rescue & Flight: American Relief Workers Who Defied the Nazis (2010). Also visit the United States Holocaust Museum website at ushmm.org

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted September 16, 2012