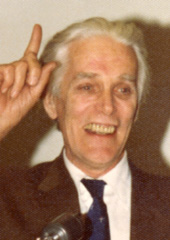

Leonard Mason (February 7, 1912-December 26, 1995), a British Unitarian humanist minister, who served churches in England and in Montreal, Quebec, was one of the outstanding preachers and public speakers of his generation.

Born in Meadow Cottage, Ainsworth, Lancashire in 1912, Leonard was the youngest of three brothers. His mother died when he was four. His father, a weaver and an amateur Shakespearian actor, was a member of the Unitarian chapel in Ainsworth (Cockey Moor), where he was choirmaster. Leonard was given a scholarship to attend a grammar school. He took on additional studies in the Bible and in ancient Greek.

Beginning in 1929, with Unitarian financial support, Mason attended Manchester University (B.A.) and Unitarian College, Manchester (B.D.). Besides religion he studied classics, philosophy, science, history, and biography. His brilliant marks were offset by several failures to pass the examination on the English Bible. He studied for a year at the Harvard Divinity School, 1935-36, during which he took time off to travel across the United States. At home on the public platform, he had begun his career as a student preacher at 18. By age 23, when he became a fully qualified English Unitarian minister, he had preached 150 times. In 1936 he went to Mansford Street Church, a mission church in East London, which he helped to become self-supporting. While there he also served as the London District Minister.

In London Mason took elocution lessons to moderate his Lancashire accent. In 1940 he married Joan Mary Edmondson. He and his wife lived through the bombing of London, caring for bombed-out families in the church basement. Their first son, Roger, was born during the Blitz. (Their other sons, Hugh and Phillip, were born later.) His church put on George Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion, taking it to the bomb shelters in the uncompleted subway stations. He played Professor Higgins.

In 1943 Mason became the minister of the Octagon Chapel, Norwich. His lecture, “Hitch-hiking across America,” was popular among the homesick Americans in nearby air force bases. This led to part-time lecturing at Cambridge University. In 1949 he became the minister at Leicester Great Meeting. There he became a religious humanist. His church did not mind, though some English Unitarians elsewhere did. His sermon on sewers, though well-written and finely delivered, did not sit so well with Leicester. One member excused him saying, “After all, he reads The Manchester Guardian: what would you expect?”

While he was minister of Great Meeting Chapel, Leicester, in 1957, he took his friend Trevor Ford of Leicester University to examine a fossil that had been found by his son Roger Mason and two climbing companions in Precambrian rocks of the Charnian Supergroup of Charnwood Forest near the city. Ford published the first scientific description of the fossil in 1958 and named it Charnia masoni. The discovery demonstrated that the Ediacara biota discovered in South Australia ten years earlier is undoubtedly Precambrian in age, confirming a prediction made by Charles Darwin in On The Origin of Species. Comparable life-forms have since been discovered in all continents except Antarctica and their distinctive life-forms have enabled the International Stratigraphic Commission to recognize a new Precambrian time period, the Ediacaran Period, preceeding the Cambrian Period.**

In 1960 Mason became the minister of The Unitarian Church of Montreal, Canada. There he filled a large church and enjoyed a reputation as the best public speaker in Montreal. He actively supported legalizing medical abortions, women’s rights, and Vietnam war resisters in Montreal. After performing the 1965 marriage of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and being subjected to much unwanted publicity, he initiated the introduction of civil marriages in Quebec. Before this time marriages had only been possible before a priest, minister, or rabbi. He served on the executive committee of the Canadian Unitarian Council, and became its President, in 1967. He was a frequent contributor to the periodical, Religious Humanism.

Mason’s speech was finely honed, straightforward eloquent English. He was an actor, a poet. Always a classical scholar, he managed to communicate with his Greek landlord in Montreal—to the landlord’s amusement—in ancient Greek. He was a hill climber, a hiker, an amateur geologist with a keen eye for and interest in nature. He read widely. He once told his Montreal congregation, “I have many books, too many. I read an average of about 100 pages of book per day. This is supplemented by newspapers, journals, a little radio and more TV.”

Invited to give the Bicentennial Lecture in Duxbury, Massachusetts in 1976, Mason chose as his topic “Why they should not have had their revolution.” He gave the sermon at a 1971 UUA General Assembly Service of the Living Tradition. He authored Bold Antiphony, 1967, a book of meditative poems, at once Canadian, English, secular, religious, humanist, and “its tone an undisclosed theism.”

Mason gave the 1975 UUA GA Berry Street Lecture, “Hubris and Humility.” In this he compared the Western legacies drawn from ancient Greece and from Christianity, oberved that “both the pagan caution against hybris and the Christian grace of humility are unacceptable to the 20th-century mind,” and declared “the Christian era ended and, brittle, we stumble into a post-Christian civilization.” Hence, he warned “A new apocalypse is bringing the people of the earth face to face with the limits at a time when the litanies of lowliness are hollow and unable to prevent doomsday.” “Our age is surely heading for the biggest cosmic retribution ever yet seen—a counterblow to human arrogance which no litanies can soften.” He saw as the solution to this modern human dilemma a non-idolatrous reverence for the earth—”When I revere the earth, I am revering at the same time all else, finite and infinite”—combined with the cultivation of the ancient Greek virtue, “sophrosyne,” or moderation.

Mason thought of God in pantheistic terms. “What is the Lord our Maker,” he wrote in his farewell sermon to the Montreal congregation in 1977, “but the vast and complex universe which squeezes the energy of an ancient explosion into a roaring sun, splashes debris to be swirled up into a planet, provides marginal seas in a backwater from a terrestrial tumult for the germination of life, molecules locked together by earth chemistry and solar radiation?” His view of man, outlined in the affirmation included in the Unitarian Universalist hymnal, Singing the Living Tradition, reflects tragic optimism:

We affirm the unfailing renewal of life.

Rising from the earth, and reaching for the sun, all living creatures shall fulfill themselves.

We affirm the steady growth of human companionship.

Rising from ancient cradles and reaching for the stars, people the world over shall seek the

ways of understanding.

We affirm a continuing hope.

That out of every tragedy the spirits of individuals shall rise to build a better world

In 1975 Mason and the Montreal church hosted the Congress of the International Association for Religious Freedom, a world-wide association of Unitarians and other religious liberals around the world. When he retired in 1977, the Montreal congregation made him minister emeritus. He moved to Kingston, Ontario in 1983, and later to Toronto, where he died.

Leonard Mason’s British sermons, pocket diaries, and other material are held by Dr Williams’s Library in London, England. His daily diary entries for 1935-36 provide a window on his travels in America and meetings with theologians, scholars, and denominational leaders in the United States while his 1938, 1939, and 1941 diaries mix reflections of world events with notes on day to day church operation. Additional sermons can be found in the archives of the Unitarian Church of Montreal, Canada. There is some biographical information in Charles Eddis’s chapter on Mason in Edward Andrew Collard, Montreal’s Unitarians, 1832-2000 (2001). See also Phillip Hewett, Unitarians in Canada (1978, 2nd ed. 1995).

Article by Charles Eddis

Posted March 10, 2008

** Paragraph added January 2016, provided by his son Roger Mason.