Charles Edwards Park (March 14, 1873-September 20, 1962) was a Unitarian minister who served First Church in Boston, Massachusetts for forty years. One of the leading exponents of Unitarian Christianity during the first half of the twentieth century, he authored books and articles on religion, prayer, local history, and the graphic artist, Frederic Goudy.

He was born at his maternal grandfather’s mission in Mahabaleshwar, India where he spent his first eight years. His parents were married in Amherst, Massachusetts before departing for India. His mother Anna Maria (Ballantine), was the daughter of a missionary while his father, Charles Ware Park (1845 -1895) was a Congregationalist minister and missionary employed by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a Congregationalist organization. His father edited the Indian Evangelical Review.

In 1881 the family returned to American where his father ministered at Congregational churches in New Haven, and then Derby, Connecticut. In 1895, his father embraced Unitarianism and accepted a call to the Unitarian Church in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, but died before he could assume the position.

Charles was by then a student at Yale University. Most of his public education had been at Derby, and after he graduated from its high school, he had prepared for college at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. He was a member of the Class of 1891. In June 1896, Yale awarded him a BA. He decided earlier to be a minister, so he enrolled as a student at the Divinity School of the University of Chicago.

During his two years in divinity school, Park assisted William Wallace Fenn, the minister of the First Unitarian Church in Chicago, Illinois. Fenn was an early mentor and lifelong friend. In 1898 Park withdrew from school after receiving a call to become minister of the First Unitarian Church in Geneva, Illinois. He was ordained to the Unitarian ministry that same year and met his future wife, Mary Turner, a member of his congregation.

In 1900, after two years at Geneva, he accepted a dual call to serve two small churches, the Second Society or Parish and the New North Unitarian Church or Third Congregational Society, in the rural town of Hingham, Massachusetts. At the same time, Louis C. Cornish, a future president of the American Unitarian Association, became minister of the town’s First Parish.

Park, who was just twenty-seven and overflowing with energy and enthusiasm, soon reinvigorated his congregations, especially at New North, greatly increasing church membership. One of his accomplishments was the building (completely funded) of a much-needed parish house for the New North Church.

Park gathered with Edward Everett Hale and others in Channing Hall at Unitarian headquarters in Boston on May 23, 1901 to establish the Unitarian Historical Society. He delivered one of the “Brief addresses” at this meeting. He believed that historical research on religious and secular topics was an integral part of his ministry. His first scholarly address to the society was given in 1907 on the topic, “Tablets and Memorials in our Churches.” It was followed in 1911 with “History of Ordination and Installation Practices.”

On September 19, 1903 he married Mary Eliot Turner in Geneva, Illinois. They had five children, four of whom lived to be adults. Their son David became one of the leading painters among the artists of the Bay Area Figurative Movement in San Francisco, California in the 1950s. Another son, Edwards Park, went on to author two books, write for National Geographic, and edit the Smithsonian Magazine.

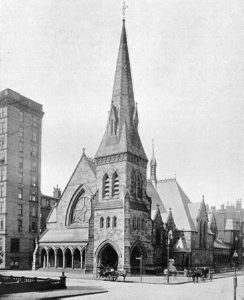

In 1906, Park’s successful ministry at Hingham brought him to the attention of the trustees of First Church, Boston who were seeking a new minister. During April and May, he preached twice to the congregation, after which the trustees asked him “if he would consider an invitation to become minister.” After thinking about the offer, he replied; “if a reasonably cordial invitation was given to him, he should be willing to receive it.” On June 30, the church officially called him, and he accepted. He indicated, however, that he would stay in Hingham until September 9 and start his new duties on October 1.

The Boston Sunday Post in a July issue reported that the new minister coming to John Cotton’s old Puritan church “was totally opposed to many Puritanical ideas of his early predecessors.” He is, they continued, “liberal, young, and fond of life in the open air” by which they meant that he was an “ardent yachtsman” as well as a baseball and golf enthusiast. And that he had, “without money or favor, fought his way single-handed in the world, and is now due to step in among men and women whose pride of ancestry is accompanied in almost every case by possession of wealth.”

At its October 1906 meeting at 25 Beacon Street, the national Ministerial Union welcomed Park to Boston as the minister of First Church. He then addressed the group on “The Spirituality of a Unitarian.”

He was officially installed as First Church’s twentieth minister in November. Paul Revere Frothingham of Arlington Street Church in Boston delivered the sermon; Edward Everett Hale minister of Boston’s South Congregational Church, and prominent author and historian, gave the prayer; William Wallace Fenn, Bussey Professor of Theology at Harvard University, read the scripture; Francis Greenwood Peabody, Dean of Harvard Divinity School charged the minister; and Howard Nicholson Brown, minister of King’s Chapel, gave the hand of fellowship. It was a remarkable gathering of Unitarians leaders.

Park’s collected sermons, preached over more than half a century, are his most enduring legacy. In them, he carefully elucidated for his congregation – and for a wider audience since many were later printed – his understanding of the teachings and message of the human Jesus. This is the Jesus of our common historical experience, as opposed to St. Paul’s theological Christ, which had come to dominate the views of most branches of Christianity. For Park, the center of his liberal Christian religious belief was always “what was in the heart of Jesus.” He thought of God as “an Indwelling Presence whose temples we are, and at the same time a Wholly Otherness entirely objective to us – God is the Primal Mind, whose thoughts create and sustain this Whole of Things.” Underlining these tenets was his belief that for man, “Life must have a meaning, a purpose, a goal, great enough to justify all the toil and suffering, and that both can and will be reached. In his religion he must find this assurance of purpose. He will find it in the Way of Jesus.”

This message remained constant through two world wars, both of which he supported as just wars, a major depression, and the rise and challenge of modernism, social activism, and religious humanism to the Unitarianism of his day. His view of the ministry differed from that of his contemporaries, John H. Dietrich and John Haynes Holmes. While they tried to educate their congregations about social issues and changing scientific ideas, Park worked to provide his listeners with a personal religion that would enable them to live securely in God’s love for them and their love for humanity.

Once settled into his regular church tasks, Park turned his attention to the larger community. As minister of First Church, he automatically became one of the directors of the Franklin Foundation. Its responsibility when he joined the corporation was, on behalf of the city of Boston, to care for and manage the industrial school, now the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology, which was established through funds left to the city in a codicil to the will of Benjamin Franklin. In addition to being a director, he was for a period also the foundation’s secretary.

In 1908, he was elected a resident member of The Colonial Society of Massachusetts. A year later he was made its corresponding secretary, a position he held for many years. He delivered his first paper, “Excommunication in Colonial Churches,” at the April 1908 meeting. In 1910 he spoke on “Two Ruling Elders of the First Church in Boston: Thomas Leverett and Thomas Oliver.” He also became involved with the work of the Massachusetts Convention of Congregational Ministers, and in 1910 spoke to them on “The Influence of Congregationalism Upon the Nation’s Religion.”

At this time, the Unitarian Sunday-School Society asked him to prepare “a life of Jesus” as part of their Beacon Series of Sunday School Manuals for junior students. He agreed, and Jesus of Nazareth was published in 1909. He further extended his community work in 1911 when he was appointed to Harvard College’s Board of Preachers. It was the start of a long working relationship with Harvard University and later it’s Divinity School.

At about the same time, he became secretary of the Massachusetts Congregational Charitable Society, which had been founded in 1786 to provide financial help for the widows and daughters of deceased Congregationalists, and then also Unitarian, ministers.

By 1916, a decade after his arrival in Boston, his ministry at First Church had taken permanent shape. His tenure was to be similar to many of the New England preachers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries whose ministerial service was essentially in one place. Once settled, they stayed for life, emphasizing pastoral care and devotional teachings, along with scholarship and denominational tasks. This was the kind of ministry that Charles Park so perfectly imitated at First Church.

Early recognition of his talent and abilities came in 1916 when the Meadville Theological School, then still in Meadville, Pennsylvania, awarded him an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree.

A year later the American Antiquarian Society elected him a Resident Member and published his first lecture, “Friendship as a Factor in the Settlement of Massachusetts,” in their 1918 Proceedings. In 1930, they were to print another essay, “The Development of the Clipper Ship.” Also in 1917 he spoke to the Unitarian Historical Society on “Possibilities of Beauty in the Congregational Order,” which was later published by the American Journal of Theology (1919). When the Historical Society established its own Proceedings in 1925, he was appointed to the publication committee. His “The First Four Churches of Massachusetts Bay” came out in its 1931 issue.

The new Dean of the Harvard Divinity School, his friend Willard Learoyd Sperry, hired him in 1926 to be a part-time lecturer in “practical theology,” a position that he held until 1943. Based on his long “practical” ministry at First Church, it proved to be an appropriate appointment. Five years later, his congregation celebrated his twenty-fifth year as their minister. Harvard University, at its 1932 commencement, awarded him an honorary STD. It was given because “He has gathered in himself the traditions of the New England ministry, and refined them by his lucent thought and sensibility.”

In spite of a demanding schedule, Park did find time to relax with his family. Starting in 1914, summers were spent in Peterborough, New Hampshire, where he often preached at the local Unitarian church. He was also a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society; the Yale Club; and Boston’s St. Botolph, Saturday, and Examiner Clubs. His hobbies included printing, photography, and woodworking.

In 1936 Park’s Unitarian ministerial colleagues invited him to deliver the Berry Street Essay, the oldest lecture series in North America. It is given at the yearly gathering of the Berry Street Conference, held during the annual meeting of the Unitarian (later Unitarian Universalist) Ministers Association. His address was “The Ethical and Spiritual Emphasis of Modern Preaching.” Unfortunately, the text has been lost.

Hingham, Massachusetts, where Park had preached from 1900 to 1906 was also home to The Village Press, a project of Frederic W. Goudy, a prominent American typographer, printer, and graphic designer. In 1938, along with Mitchell Kennerley and Will Ransom, Park published Intimate Recollections of The Village Press by Three Friends. This limited edition book was issued for the 35th Anniversary of the Press; Park’s contribution covered the years it operated in Hingham, which coincided with his ministry in that community. Even though their paths separated after Hingham, the two men remained lifelong friends, tied together by their interest in printing.

When his old church, the Second Society in Hingham, celebrated the two hundredth anniversary of its meetinghouse at a gala service on the evening of June 21, 1942, Park journeyed from Boston to deliver one of the two addresses. The occasion, the church records noted, “was carried to fulfillment in a dignified, impressive, and pleasing manner.”

The next year he wrote his last historical essay, “The Beginnings of the Great Awakening,” which was published in the 1943 Publications of the Society of the Descendants of the Colonial Clergy.

Park decided in 1946, when he was 73, that it was time to resign from First Church, after having served as its minister for 40 years. The parish made him minister emeritus and held a celebratory service in Edward Everett Hale Chapel to honor Park and his wife for their long, devoted, and faithfully shared pastorate. His friend and Harvard dean, Willard Learoyd Sperry delivered the principal address, calling Park a “simple preacher” who understood “the complexity of life and the world and of self-disciple, by which order is finally brought out of chaos.” Time magazine in its July issue declared Park to be “the Grand Old Man of U.S. liberal pulpits.”

That same year, Harvard University Press published his The Inner Victory: Two Hundred Little Sermons (1946). These homilies, which had been written throughout his ministry, were just a page long, each with a Biblical text, and about common moral and ethical subjects. As such, they could be used as a daily private meditation manual. In its review, the liberal Baptist Crozer Quarterly reported, “It is a sheer delight to find thought so happily wedded to feeling that religion becomes invested with a genuine dignity.”

Retirement freed Park from daily pastoral duties and the need to prepare sermons. He continued to preach occasionally at First Church and at neighboring parishes but he now had more time to write books.

In 1947 Park was invited to deliver the annual Minns Lecture. These are administered by King’s Chapel and First Church. His lecture, Christianity: How It Came To Us, What It Is, What It Might Be was the first in this renowned series to be published. Christianity, he argued, is wholly about its founder, Jesus, who “gathers all the essential truths of our Christianity in himself.” Therefore, it demands us to “love what he loved, to be what he was, to do what he did, and to worship as he worshiped.” When individuals do this they discover that the “Christianity of Jesus offers a religion that lives and operates primarily in your own heart” and gives you “a sense of individual worth in God’s eyes; a moral incentive that is prompted by love of God and operates without compulsion; and a hopeful, rejoicing partnership in God’s preset purpose and ultimate victory.”

Beacon Press published a collection of sermons drawn from his long ministry, Creative Faith in 1951. “Grateful parishioners” underwrote its publishing cost, and Palfrey Perkins produced a brief foreword. Park, he said, was primarily a preacher and while “the church was seldom filled to overflowing” the “spoken word has always been his first interest,” and, as a result, “few men have been so faithful to the pulpit.”

On December 12, 1944, Park met with twelve Greater Boston Unitarian leaders at First Church to discuss the formation of a group that would revitalize and nurture a “Unitarian Christian Advance” within the denomination. Included in this group were Palfrey Perkins, Dana McLean Greeley, Vivian T. Pomeroy, Paul Harmon Chapman, and Herbert Hitchen. This gathering eventually evolved into the Unitarian Universalist Christian Fellowship (UUCF), an organization that fosters liberal Christian teachings and values.

One of the projects of the UUCF was the periodical, The Unitarian Christian. Park served as its editor-in-chief from 1952 until 1958. Under his leadership, it went from newsletter format to a magazine-style paper quarterly and refined its editorial policy to reflect a “more devotional and less polemical” stance. As he wrote in 1952, the magazine’s ideal was “to be not only a thoughtful, but a thought-provoking influence, to honor sincerity; to encourage fearless candor.”

In 1955 Beacon Press published Prayers, a collection of meditations. First published as Beginning the Day in 1922 by the Unitarian Laymen’s League, it had already gone through a number of editions.

After his death, the Unitarian Universalist Christian Fellowship published two collections of Unitarian Prayers (1984 and 1989), which included some by Park. When Park prayed, wrote Carl Scovel, “He prayed with the openness of a child, and yet he prayed also with eloquence of a man.” As a result, “he draws us into the circle of his prayers and helps us to pray for ourselves. This, as he said, is all he wished to do.”

His last book, which was based on his second Minns Lecture (1951), was The Way of Jesus (1956). It was directed toward parents with children who sought to be Christians by following the pathway of his teachings rather than the theology surrounding him. Park’s emphasis, therefore, was on the historical and human Jesus of Nazareth as described in the first three Gospels. Approached in this way, he wrote, one finds a Jesus with “a strong, clean, reverent, generous nature, a great heart, a singularly keen and active mind, a boundless sympathy and a practical solicitude, and exceedingly sensitive to spiritual values. He lived his life just as near to the heart of God as a human creature can get. His foremost aim was to do the will of his father in Heaven.” The essence of the way of Jesus, of all our living then, is summed up by that ancient teaching, “love to God and love to man.”

After a long illness Charles Park, 89 years old, died at his beloved Marlborough Street Boston home. Over 800 parishioners, friends, ministerial colleagues, faculty members of Tufts and Harvard Universities, as well as representatives from several denominations, attended the funeral at First Church. Rhys Williams, one of his ministerial successors, conducted the service, and the prayer was given by his friend of fifty years, Palfrey Perkins, minister-emeritus of King’s Chapel.

That November an anonymous donor purchased his home and gave it to the Unitarian Christian Fellowship, which they used for several years for an office, meeting space, and apartment for their executive secretary. In 1965 the trustees of First Church purchased the building adjacent to its sanctuary, 66 Marlborough Street, and named it for Park. It is used for the church’s office, for the Sunday School, and for general group meetings. Fortunately, it was not destroyed when an arsonist torched the church in 1968, and is a reminder of, as Rhys Williams declared, “The beauty of his spirit [which] lovingly nurtured our church for almost sixty years.”

Sources

Park’s American Unitarian Association ministerial file is in the archives of the Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

For biographical data see Decennial Record of the Class of 1896, Yale College (1907); The Christian Register (1906); Alanson P. Spencer, “The First Church in Boston,” The Christian Register (1906); “Services at the Installation of the Rev. Charles Edwards Park As Minister of the First Church in Boston November Seventh, 1906” (1907); Who Was Who in America, vol. 4; Rhys Williams, Charles Edwards Park (1962); “Charles Edwards Park,” in David Robinson, The Unitarians and the Universalists, (1985); “Charles Edwards Park,” in Mark W. Harris, Historical Dictionary of Unitarian Universalism (2004); “The Man Who Stayed to Preach,” Time (1946); and obituaries in The Boston Globe (1962); Boston Herald (1963); and Peterborough Transcript (1962).

See also Donald F. Robinson, Two Hundred Years in South Hingham: The Story of a Church and a Community, (1980); Rhys Williams, “A Statement from the Minister,” First Church in Boston Charles Edward Parker House (19??); “UCF to Honor Dr. Park,” Unitarian Universalist Register-Leader, (January, 1963); D. J. R. Bruckner, Frederic Goudy, (1990); Thomas D. Wintle, “‘Missions to Ourselves’ and The Beginnings of the UUCF,” and “Introduction: The Unitarian Universalist Christian: A Fifty-Year Retrospective,” in The Unitarian Universalist Christian (Volume 51-52), (1996-7).

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted April 25, 2013