Helen Richmond Young Reid (December 11, 1869-June 8, 1941) was a Montreal social worker involved in local, national, and international reform movements. A life long Unitarian, she founded and directed a number of charitable and educational organizations. She served on government committees and she published articles and books in the fields of social welfare, public health, and immigration. Reid travelled widely and enjoyed a circle of friends from many countries.

Reid was born and lived her life in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. She had an older brother and two younger sisters. Her mother, Eliza Anne McIntosh Reid led a life of service in the community, in the Unitarian church, and in a number of women’s organizations. Her father, Robert Reid was proprietor of the Montreal Sculpture and General Marble and Granite Works. He was an artist and a businessman.

The Reid family was part of the close knit Scottish immigrant community that dominated commerce in Montreal in the nineteenth century. Most had been Presbyterians until the Disruption of 1843 split the established Church of Scotland. In Montreal many joined the recently formed Beaver Hall Unitarian congregation. The Reid family was connected by church and marriage ties to a number of other prosperous Montreal Unitarian families such as those of George Washington Stevens and John Young. Her family provided ample support so she never lacked the resources needed to follow her interests. Reid enjoyed entertaining guests, travelling, and golf. At the time, academic careers and marriage were thought by most to be incompatible. Reid never married and she never had children. She lived in the family home most of her life, with her parents, her sister Edith, and the family’s servants. The home on Sherbrooke Street was in Montreal’s fashionable St. Antoine Ward (also known as “uptown” and later as The Square Mile).

Reid attended the Montreal School for Girls, and graduated as an associate in arts in 1884. When eight young women including Helen—recent graduates from the school—met at the Reid home to discuss their future plans, someone suggested they ask for entry to McGill University. Reid’s mother encouraged them to apply. Helen Reid and Rosalie McLea were delegated to meet with the principal, John William Dawson, to request entry. Helen later reported that she was fourteen and ‘scared’. Principal Dawson supported the education of women but he asked for some time to consider their proposal.

Dawson had started the McGill Normal School in 1857 to train men and women as elementary and high school teachers for Protestants in Lower Canada. After a tour of European schools in 1870 he had enlisted Anne Molson to found the Ladies’ Education Association of Montreal and then he encouraged Molson to lobby the corporation of McGill University to accept women students.

After two weeks consideration, the women were told that the university did not have the funds to start separate classes but with more applicants “…the prospects would be brighter…” More applicants were obtained but the matter of women’s entry was not settled until September 1884, when businessman Donald Smith offered to donate $50,000 for the education of women at McGill.

The women in this first class and later classes often referred to themselves as the ‘Donaldas.’ The name was derived from Donald A. Smith, later Lord Strathcona. It was Smith who had donated $50,000 to endow a college and separate classes for women at McGill University. According to Reid’s article “Women’s Work in McGill University” published in the Dominion Illustrated Monthly (May 1892), Sir Donald Smith later increased his endowment to $120,000 to provide for co-education classes.

The first class of women graduated from McGill in 1888 but Reid had left the group during her third year because she had typhoid fever. For a time she served as the editor of the “Ladies Department” for the McGill newspaper, the University Gazette. She returned and graduated in 1889 with first class honours in Modern Languages. She also received the Governor General’s Medal for women graduates. She continued her education in Europe, studying at the University of Geneva and in Germany.

Reid and her fellow graduates opened a lunch room at 47 Jurors Street to give factory girls an alternative to sidewalk lunch breaks. Soon the kitchen expanded into a dining room, boarding house, and girl’s club. In 1894 the club moved to 84 Bleury Street and evening classes were added. By 1915 it had grown into the University Settlement in the heart of Montreal’s Jewish and Chinese quarter and it had a half dozen staffers. The McGill women also started the first Children’s Library in Montreal. It opened in 1895.

In 1898 the National Council of Women of Canada petitioned the minister in charge of the Canadian Section of the upcoming Paris International Exhibition of 1900. They asked him to allocate adequate space at the Paris exhibition to feature women and their accomplishments. The minister suggested the Council prepare a book which would give “the history, the achievements and the position of Canadian women as a whole.” They accepted the offer and a book was compiled by women volunteers from across Canada for distribution in Paris. Reid was put in charge of two sections of the resulting book, Women of Canada: Their Life and Work (1900).

Reid was a charter member of the Charity Organisation Society (CSO) when it was formed in Montreal in 1900. Unitarian minister William Sullivan Barnes and others had previously attempted to form a charity organization but those efforts failed. A half dozen of the larger Canadian cities would form CSO groups to coordinate regional charity services. They were modelled on Toynbee Hall and Hull House. The CSOs used moral efforts along with physical (food, money, clothing, shelter, etc) means to ensure permanent relief through “. . . social and sanitary reform, and the inculcation of habits of providence and self-dependence.”

Reid served on the Board of Directors of the Montreal Council of Women, 1900-03. The Council of Women of Canada had been founded in 1893 by Lady Ishbel Aberdeen, the wife of the then Governor General of Canada. Reid’s mother Eliza Anne Reid had been one of the founders of the Montreal council in 1894. Her mother also served as vice-president. Lady Aberdeen “asked that the members concern themselves with all aspects of life in the city to bring about the necessary changes in attitudes and legislation with a view to improving the lot of women and their families.” One of Reid’s first publications was a paper she read before the Montreal local council on The Problem of the Unemployed (189?). Well received, it was published by the national council. One of the achievements of her local council was starting and administering one of the first branches of the Victorian Order of Nurses (VON) in 1900. Reid and her mother were both involved in the VON.

Reid, a third generation Unitarian, was a life long member of the Church of the Messiah, later known as the Unitarian Church of Montreal. Her parents and relatives were very active in the funding and construction of the new Unitarian Church building on Sherbrooke and Simpson Streets. It opened in 1908.

Reid was one of the first medical social workers in Canada. She was placed in charge of the relief committee of the Victorian Order of Nurses during the great typhoid epidemic in Montreal, 1910-11. She also established the first education and publicity committees, national and local, for the Victorian Order of Nurses. In 1916 a journal article by Reid, “Social Service and Hospital Efficiency” was printed in the Canadian Public Health Journal. In it she compared Montreal’s achievements to similar work in Boston, New York, and Chicago. Other Reid articles in the same journal include, “Some Opportunities for Health Service from a Volunteer’s Point of View” (1919) and “The School Child and Nutrition” (1919).

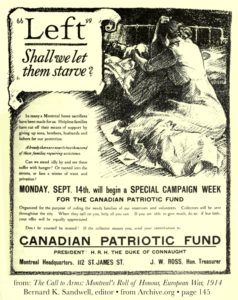

The Canadian Patriotic Fund was established by the Government of Canada at the beginning of the First World War in 1914. Reid chaired the Montreal branch auxiliary. The fund was started to provide support to wives, children, and dependents while soldiers were away from home. Its administration was centered in Ottawa with branches across the country. Volunteers in each community raised funds through donations and grants and then distributed those funds. Essentially a social work program, funds were distributed to wives of soldiers. Reid, an unpaid volunteer, managed 800 volunteers and employees and was responsible for distributing $75,000 of aid every month. Reid summarized and presented the results of the Canadian Patriotic Fund work in her book War relief in Canada (1917).

Why was the Canadian Patriotic Fund successful? According to Paul Kellogg who wrote “A Canadian City in War Time” for the social work journal Survey (March 1917), “The answer lies in the woman who brought experience and courage and sacrifice and more beside—a genius for organization and the unmistakable flame of leadership. This is Helen R. Y. Reid, director and convener of the Ladies’ Auxiliary. . .” The war touched Reid’s own family; her cousin Francis Chattan Stephens was injured in France and spent months in an English hospital recovering. Her aunt Frances Ramsey Stephens, a nephew, and two family servants died when the Lusitania was sunk by Germany in 1915.

King George V named Reid a Lady of Grace of St. John of Jerusalem in 1915 in honour of her war work. Her contributions were also recognized with honourary degrees from Queen’s University in 1916 and McGill University in 1921. Reid was just the second McGill woman graduate to receive an honourary degree. She was awarded the Medaille de Reconnaissance from The French Republic in 1921 for her services to French reservist families in Canada and the Red Cross Gold Medal from the Italian Red Cross, 1922, for services to Italian reservist families.

In 1917, as the U.S. was entering World War I, Reid traveled to over 20 U.S. cities lecturing on her experiences with war relief efforts in Canada and reporting on the Canadian Patriotic Fund’s work in Montreal. In June, a month after the United States entered the war she spoke on the “Patriotic Fund of Canada” at the National Conference of Charities and Correction in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “All of the problems met with in peace times we meet again in wartime in our soldier’s families,” she said, “This is one of the tragedies of war, but it is also the greatest opportunity for community workers.” The Social Problems of the War were addressed at the conference in the keynote speeches delivered by Herbert Hoover and former U.S. President and prominent Unitarian, William Howard Taft.

Reid was back home in September to attend the General Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches which met in Montreal, Canada September 25-28, 1917. Reid spoke on her Canadian Patriotic Fund work during the Unitarian Women’s Alliance luncheon meeting on Wednesday. This was the first time the General Conference had met outside the United States. After delivering the opening speech, Unitarian leader and former U.S. president William Howard Taft, introduced a resolution affirming Unitarian support for the U.S. Entrance into World War I. Taft’s martial resolution preempted the official conference report presented later by Unitarian minister John Haynes Holmes. As fear gripped the United States and America entered its First Red Scare period, the patriotism of Holmes and pacifist ministers would come under increasing attack.

Four days after the Unitarian conference closed, Reid was in LaPorte, Indiana to address the State Conference of Charities. Reid remained busy during fall 1917; She spoke to Associated Charities in Lansing, Michigan; she visited the Christamore settlement in Indiana and she addressed Red Cross workers, the Young Women’s Christian Association, and the Social Workers Club in Indianapolis; she spoke to the Children’s Aid Society in Baltimore, Maryland; and to the Council of Social Agencies in Cincinnati, Ohio. A few months later she met with Mrs. Joseph Bowen, chair of the woman’s committee of the Illinois State Council of Defense. It was Bowen who first suggested war widows should wear gold stars instead of black mourning clothes.

Reid was instrumental in the development of the School of Social Work at McGill University and she was its director for fifteen years. She was a lecturer on public health and she mentored the next generation of social workers, people like Jane B. Wisdom and Charlotte Whitton. Wisdom graduated from McGill in 1907 and worked for a time with the Charity Organization Society (COS) and the University Settlement. Reid also chaired the Committee on the Proposed Course for Graduate Nurses which led to the beginning of the School of Nursing at McGill University. Nursing and social work, two professions that would be primarily composed of women for many years. In 1918, she was appointed a member of the Corporation of the University by the Board of Governors, as a Governor’s Fellow. She was the first woman to receive such an appointment. It was made chiefly because of her conspicuous services in connection with the administration of the Canadian Patriotic Fund in Montreal. She would serve as a Governor’s Fellow at McGill for 15 years.

After the war, Reid ran a health clinic through the Patriotic Fund. During its first year of operation, 1919-1920, the health clinic saw 1260 children and babies from former soldiers families. The infant mortality rate in Montreal had been 182 per thousand births during the war years. Reid tapped her social service students at McGill to assist with the University Settlement and Baby Health Center work. Later she presented the results of this health clinic work to the general public by publishing A social study along health lines: of the first thousand children examined in the health clinic of the Canadian Patriotic Fund, Montreal Branch (1920). She followed up by distributing complimentary copies, making sure to paste her business card on the flyleaf.

In 1920 Reid was elected secretary of the Canadian Public Health Association. She also served as one of its three vice-presidents. She was also vice-president of the Family Welfare Association of America; the first woman appointed to the Dominion Council of Health; a member of the Canadian Repatriation Committee,1918-19; vice-president and co-founder of the Canadian Council; a member of the Dominion Council of Health, 1919; president of the Montreal Council of Social Agencies; a member of the Financial Federation; and president of the Child Welfare Association.

In the 1920s when Ida M. Cannon was the President of the American Association of Hospital Social Workers, Reid served on her advisory committee along with Dr. Richard Cabot. Cabot and Cannon were both Boston Unitarians. Cabot had established the first in-hospital social service department at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts in 1905. And he had hired fellow Unitarian Ida Maud Cannon as Mass General’s first hospital social worker. Reid was also connected to Cabot and Cannon through Rev. John Lochhead, a Presbyterian minister whom she had worked with during the 1910 Typhoid epidemic. The social service president at Montreal General Hospital, Lochhead had studied in Boston with Cabot.

Reid’s father Robert died in 1919. Her mother Eliza Anne McIntosh Reid, who was listed as a 77-year old invalid on the 1921 census, died in 1926. Reid appears to have inherited enough money to continue her committee work, support her travel, and to continue living the Reid family lifestyle. Reid’s 1927-1934 autograph book, now in the McGill University Archive, contains many poems and messages written by friends and visitors.

In 1931 when the Methodist, Presbyterian, and Anglican theological colleges withdrew their support for the McGill Department of Social Work, the school was closed. Two years later the Montreal School of Social Work opened with Dorothy King as director. It was governed by a board of trustees that included Helen Reid and Jane B. Wisdom, one of the students Reid had mentored at McGill.

Reid was a member of the Advisory Council on Women’s Immigration and she chaired the immigration division of the Canadian National Committee on Mental Hygiene. Two publications grew out of her pioneering social work investigations into immigration. She collaborated with Charles H. Young to research and write The Ukrainian Canadians, a study in assimilation (1938), and The Japanese Canadians (1931). The second title concentrated on Japanese in British Columbia; including immigration, settlement, and expansion. It looked at urban colonies, commercial activities, relations with other Canadians, and social problems in Japanese settlements. Young and Reid thought that assimilation problems were caused by the resistance of anglophone British Columbians and they suggested that quotas might slow and defuse that resistance.

In 1936 Reid [age 67] wrote “Lest We Forget,” a final summary report on the Canadian Patriotic Fund. The four national fund-raising campaigns during the first World War had brought in 50 million dollars. Because of volunteers, the overhead cost of the campaigns, including administration and services had run to less than half a million dollars or about one percent. Post-discharge relief efforts ended in 1922 and local branches were closed in 1924. The Ottawa office and the management committee of seven (including Reid) finally disbanded in 1936.

The Reid home in Montreal has been described as a gathering place for intellectuals when they were visiting Montreal. Guests included William Butler Yeats, Vachel Lindsay, Dorothy Thompson, and Harold Nicolson. Reid worked with and corresponded with a number of prominent individuals including social welfare pioneer Jane B. Wisdom. She also translated stories, poems and articles from French and German for journals and magazines. Reid continued her interest in McGill University and its students throughout her life. When she entertained guests, “Frequently she would telephone the warden of Royal Victoria College (the women’s college at McGill) to say, ‘Come if you can on Sunday. I have so and so with me. And bring any student who may be interested.’”

Dr. Susan Cameron Vaughan, the Warden [head or principal] of Royal Victoria College wrote in 1941, “My personal recollections of Helen Reid begin in my student days when she came, fresh from travel to address one of our undergraduate societies. To my unlettered inexperience, she appeared as a perfect example of the cultured woman of the world, beautifully dressed, poised, fluent and forceful.” About the Sunday receptions, Ms. Vaughan wrote, “And we would go and find a room filled with a most diversified company, all Dr. Reid’s friends and…our hostess with her halo of white hair…the memory of a gracious presence, thoughtful, kindly, full of vitality and at times of an infectious gaiety…a lifetime of highly intelligent and altruistic activity…. And it must be remembered that in many of the organizations named she was not only director but had been the initiator.”

In her mid-sixities, Reid remained active: She hosted a luncheon for the the Victorian Order of Nurses in Ottawa, May 1935; attended an Ottawa meeting on “Problems in Maternal Care” under the auspices of the Canadian Welfare Council, December 1935; was at the annual Canadian Welfare Council meeting at Toronto, June 1936; the annual meeting of the Victoria Order of Nurses, April 1937; she was elected a vice president of the Canadian Welfare Council, June 1937; and she was honoured with a life membership in the Victorian Order of Nurses, April 1939.

She also received additional civic honours. When she was made a Commander of the British Empire (CBE) in 1935, a newspaper described her as one of the outstanding figures in the social service field in Canada. The Montreal Star said the CBE award was “in recognition of her patriotic and philanthropic services.” She was awarded a Jubilee Medal in 1935 and the Coronation Medal in 1937.

Jane B. Wisdom who had boarded in Reid’s Montreal home in 1935-36, returned in February 1941 to assist Reid who was terminally ill. Reid attended her last University Convocation in late May and died a few days later. She is remembered, appropriately, at McGill University. She donated her collection of books to the library and there is a Helen R.Y. Reid Scholarship funded by a legacy from her estate. It is awarded annually through the McGill Women’s Alumnae Association Scholarship Fund. In the memorial service at the Montreal Unitarian Church of the Messiah, Angus Cameron, minister, said, “The torch of human aspiration is passed from the hands of a noble character to our own. May we keep the faith!” Her body was cremated at Mount Royal in Montreal.

The National Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches

was restricted to churches in the United States until 1911 when the group voted to replace the word “National” in the organization’s title with the word “General.” This opened the conference to Canadian Unitarian congregations.

In 1915, when American Unitarians attended the 26th biennialGeneral Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches in San Francisco, California their chartered train took the Canadian trans-continental route. Starting in Boston, they traveled across Canada from Montreal, Quebec to Vancover, British Columbia. As the 260 U.S. Unitarians crossed Canada they visited local Unitarian congregations. They found the Canadian churches in crisis because so many men and ministers had left to fight in the war.

From Vancover the Unitarians headed south to San Francisco to attend the conference and to take in the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. The U.S. conferees voted to provide supplemental funds to help support struggling Canadian congregations.

They also voted to hold the next biennial conference in 1917 in Montreal, the first time outside of the United States.

Sources

Two poems by Reid along with some early letters from poets Charles G. D. Roberts and Louis-Honoré Fréchette are in the Helen Richmond Young Reid fonds, McGill University Archives, Montreal, Quebec. Two boxes of correspondence between Reid and Charlotte Whitton are in the Canadian Council of Social Development Fonds at the National Archive of Canada (bac-lac.gc.ca). Reid letters can also be found in the Jane B. Wisdom fonds, Nova Scotia Archives, Halifax, Nova Scotia. The Montreal Church archive holds a typewritten manuscript by Helen Richmond Young Reid, My Mother Mrs. Robert Reid: Some notes on her life in and for the Church of the Messiah (1926).

Detailed biographical information on Helen Reid and her mother Eliza Reid along with an extensive bibliography are found in Virginia Martin, “Give Us Courage: the Contributions of Helen Richmond Young Reid,” in Invisible Influence: Claiming Canadian Unitarian Universalist Women’s History (2011). Rememberances of Reid by a long-time fellow McGill staff member are found in Susan Cameron Vaughan “Helen R Y Reid” McGill News (1941). Also useful is Phillip Hewett, Unitarians in Canada (1995).

In addition to publications mentioned in the text, Reid wrote “The Montreal Relief Committee” in The Call to Arms: Montreal’s Roll of honour (1914).

For more on the relationship between Canadian and U.S. Unitarians see “The Uneven Dialogue: Relations Between Canadian and American Unitarians, 1832-1982” The Proceedings of the Unitarian Universalist Historical Society (1982-83).

Useful background information on social work in North America, women at McGill, and social work in Montreal in the first half of the twentieth-century is found in Suzanne Morton, Wisdom, Justice and Charity: Canadian Social Welfare Through the Life of Jane B. Wisdom, 1884-1975 (2014). For more on women at McGill University see Margaret Gillett, We walked very warily: A history of women at McGill (1981); Grace Ritchie England “The Entrance of Women to McGill” in The McGill News (December 1934); and Royal Victoria College Warden, Susan Cameron Vaughan’s Diaries and Daybooks: 1905-1937 in the McGill University Archives. Copies of the McGill newspaper, the University Gazette from the 1890 era are available at archive.org. There is an entry for Reid in Who’s Who in Canada (1936-39). Obituaries appeared in the New York Times (June 9, 1941), the Montreal Star (June 9, 1941), the Montreal Gazette (June 11, 1941), and other papers. McGill student publications can be accessed on-line at archive.org

Article by Jim Nugent and Virginia Martin

Posted April 28, 2017