Elmo Arnold Robinson (January 1, 1887- January 17, 1972) was a Unitarian Universalist minister, a professor of philosophy for thirty years at San Jose State University in California, and a scholar of American Universalism, especially its history in Ohio and Indiana.

He was born in Portland, Maine to Mary (Barton) and Edgar Lewis Robinson, a salesman of wholesale groceries, tea, and coffee. Both his grandfathers had been lumbermen. His early education was at the city’s public schools. As his parents were devoted Universalists, they sent him to their Congress Square Universalist Church’s Sunday School. When he was fourteen his father moved the family to Rochester, New York. There he attended East High School and “learned to love two things—study and the Universalist Faith.” He wondered about becoming a minister but his parents advised against that career, so as he enjoyed mathematics, he started to consider a career as an engineer.

After graduating from high school in 1905, Robinson elected to go to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), even though he had a scholarship from the University of Pennsylvania. At MIT he majored in biology and public health and was active in Universalist Church programs, especially its national youth organization, the Young People’s Christian Union.

During his senior year he wrote, with another student, “External Temperature and Cutaneous Blood-Flow,” which was published by the American Physical Education Review. It was the first of well over one hundred articles on many topics that he was to pen. That spring he also wrote his thesis, “An investigation of the extent of the bacterial pollution of the atmosphere by breath-mist.” In June he received his B.S. degree.

After graduation, to the amazement of his MIT friends, Robinson began theological training instead of securing an engineering job. For him, he observed later, “a general altruistic impulse to do good, together with a family inheritance of an optimistic faith,” led him to the ministry. That autumn he studied for a semester at the Universalist (Crane) Divinity School at Tufts, and then transferred to the non-denominational Union Theological Seminary in New York City for the next year and a half. His final year was spent in upstate New York at the Universalist founded Theological School of St. Lawrence University.

While at Union, he declared, “I used to wander among the slums of the East Side, visiting night courts, settlement houses, and other institutions. Like Buddha, I became aware, as I had not been fully aware before, not only of the suffering and evil, but also of the inequalities and injustices in our national life. These influences, catalyzed by a few professors and fellow students, turned me into an ardent socialist.”

During his year at St. Lawrence he served as student minister for the nearby Universalist churches in Henderson and Ellisburg, New York. In June 1912 he graduated with the B.D. degree, and a few days later was ordained into the Universalist ministry by the Black River Association of the New York State Convention of Universalists. The ceremony was held at the Universalist Church in Watertown, New York; the Dean of the Theological School, Dr. John Murray Atwood, gave the Charge to the Minister; and the Reverend Henry Clay Ledyard, Christian socialist, pacifist, and labor advocate, preached the sermon.

Surprisingly, instead of immediately taking a parish, Robinson spent the next year as a laboratory assistant at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. Then, “sight unseen,” he was hired, upon the recommendation of Dr. Lewis B. Fisher of the Universalist Ryder Divinity School, to be the minister of two Universalist congregations; Anderson and Pendleton, Indiana. He accepted, arriving in Anderson early in September 1914. He brought with him his bride, Olga Mary Kelsey; they had been married in her parent’s home at Fort Covington, New York just prior to setting off for Indiana.

Robinson was minister at Anderson for three years, 1914-1917. During his time in Anderson, he wrote, he “plunged into the typical routine of the conventional ministry: preaching services, Sunday School, and pastoral calling.” He did the same in Pendleton. In addition he organized a youth group, a men’s club, a boy’s club, and a study club as well as having the church sponsor public concerts and educational slide lectures. All of this was to make “Universalism known in the city.”

In the summer of 1915, Robinson, along with his wife and parents attended state and national Universalist Conventions in California. “Our party left Chicago in two special trains on July second,” he reported. “In Pasadena we were housed in a beautiful cottage hotel and served an abundance of fruits and vegetables. The Los Angeles area, smog free, charmed us all.” After the convention sessions they visited the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco and the Panama-California Exposition in San Diego.

Robinson’s wife Olga received her ministerial license in 1915. The following year, on December 11, 1916, their first child was born. Perhaps the most significant aspect of his Indiana ministry, was his discovery that there was no material about Universalism available at the Indiana State Library. When its librarian suggested he should “write something” about the movement in the state, he did just that. The result was his invaluable historical essay “Universalism in Indiana,” which the Indiana Magazine of History published in 1917 in two parts (part 1, part 2).

Things were encouraging for his Anderson congregation until criticism from Indiana Universalist Convention leaders, over his belief that moral ideas and politics rightfully mixed, created tension. Robinson had written a resolution supporting a “Christian witness for peace even in time of war.” In May 1917, A few weeks after the United States entered World War I, Robinson resigned from his Anderson ministry. In June he registered for the draft.

That September Robinson was called by the Universalist church in Plain City, Ohio. It was to be a short pastorate of just two years, and during the first year he was also the minister at Woodstock. During the second year he elected to take post-graduate courses at Ohio State University in Columbus. His goal was to earn a doctorate in American history and write a thesis on Universalist history. But the family’s financial needs were so great that he had to give up that idea and take on a second job as a bank teller.

Soon after his arrival in Ohio the Universalist State Convention appointed him to its Historical Research Committee. That committee then arranged with the Ohio State Historical Library at Columbus to be the depository of Universalist publications, the State Convention archives, and the records of as many local churches as possible. Robinson then began writing his The Universalist Church in Ohio, which he did not finish until 1922. Its purpose, he wrote, was “to present all the important facts and typical incidents, whether they be favorable or otherwise, concerning the Universalist Church in Ohio, leaving to others their interpretations and use.” The Ohio Universalist Convention published it in 1923.

He had left Ohio for California several years before that book came out. In 1919 the Unitarian Church in San Diego asked him to be their Assistant Minister in charge of Religious Education programs and he had accepted their call. Robinson considered Sunday Schools and youth groups to be a positive part of church life, and supporting and improving them had always been an essential part of his ministry. During his time in San Diego he was granted ministerial fellowship by the Unitarians. His last child, a second son, was born in 1921.

The Robinsons moved to the Unitarian Church of Palo Alto, California in December 1921. During his five years at Palo Alto he began to reflect on his life as a minister. “The stimuli of a new environment and congenial church work inhibited pessimism,” he wrote later, “yet I was not without the disillusionments which usually come in middle life. The two religious denominations with which I was affiliated. . . . were then in a slump. . . and I could not avoid acknowledging that, preaching peace and the social gospel as warmly as I might, my efforts had negligible effects. I began to be uneasy.” To help him understand that uneasiness he took graduate courses during the autumn of 1925 at Harvard Divinity School. In the end, after much reflection, Robinson became convinced that he needed to seek a new direction for his life, so in June 1926 he resigned as minister of the Palo Alto church to explore other options. He worked as an administrator for the American Civil Liberties Union in San Francisco and he taught algebra and science at the Lassen Union High School in Susanville, 1926-27. Doing the latter he learned how much he enjoyed teaching.

In 1928, when the State Teachers College at San Jose (later called San Jose State University) asked him to join its faculty, he accepted. At first he taught mathematics, psychology, and the sole philosophy course. He soon learned, however, that philosophy was his main interest as a teacher; so he began studying for an M.S. in philosophy at Stanford University. By 1933 he had completed the required thesis—on British philosopher Herbert Wildon Carr—and had received his degree. Carr was a Visiting Professor of Philosophy at the University of Southern California from 1925 until his death in 1931.

As more students majored in philosophy, a Philosophy Department was formed, and the university promoted Robinson to the rank of Professor of Philosophy and Chair of what was to become a four member department. He taught for thirty years at the university. When he retired in June 1958 he was named professor emeritus. Throughout his academic career he wrote articles on philosophy, psychology, ethics, and education for magazines such as School and Society, Educational Forum, Educational Theory, and The Christian Century.

The last few years of the 1930s were painful ones for Olga and Elmo Robinson; their marriage developed problems that eventually led to divorce in 1940. In time he found a second partner, Elizabeth Magers. She had done her undergraduate work at the University of Illinois, and then earned the M.S. and Ph.D. at the University of Iowa. She was an Associate Professor at Vassar College, 1927-44. They married in 1942.

In 1936 the Fellowship Committee of the California Universalist Convention had suspended Robinson’s Fellowship saying that teaching was not ministerial work; he appealed their verdict to the Central Fellowship Committee, which laid the matter ”on the table,” and there it died. So he never lost his Universalist Fellowship status. Later the Unitarians also questioned his Fellowship, took it away, but eventually restored it.

Some form of ministry was always important to Robinson and throughout his years of teaching he often preached at Unitarian or Universalist Churches and Fellowships, and several times was a visiting Professor at the Starr King School for the Ministry. In addition, he was an active lay leader in the San Jose Unitarian Church.

When the Unitarians and Universalists consolidated in 1961, ministers were asked to fill out a ministerial form for the new denomination. Robinson wrote, “I take a broad, inclusive view of religion, and have no urge to attach labels to myself, either theological or philosophical. . . . I think the role of our church is to provide a home for the come-outers and the never-was-anythings, give them a genuine appreciation for religion, help them to self-understanding and reverence, and promote a unity out of their diversity.”

Throughout his career Robinson was an active member of several professional and social organizations; these included the American Philosophical Association, the American Association of University Professors, and the Federation of American Scientists. Active in the Sierra Club of California, he enjoyed hiking, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Other leisure pursuits included playing the piano, dancing, family games, and reading fiction.

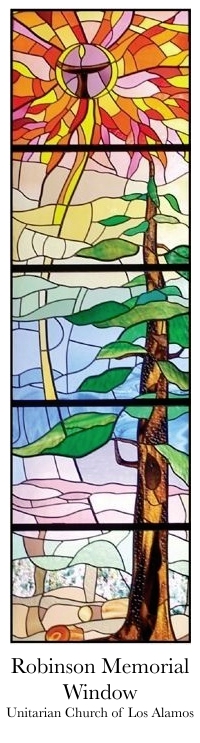

Soon after his retirement he and Elizabeth moved to New Mexico where he became minister at the Los Alamos Unitarian Church. He was its first minister and served the congregation from 1959 until 1962. When he retired both he and Elizabeth were made Minister Emeritus. Mia McLeod, a member of the congregation wrote, “He came to us when we changed from a fellowship to a church. He and his wife Betta were loved by everyone.” Some years later, in 1985, after both Robinsons had died, the congregation raised funds for a stained glass window to celebrate “their” ministry. Since the Robinsons had owned a redwood grove in California, “so that no one would be able to cut down these majestic trees,” the window’s central feature was a redwood tree with the Flaming Chalice of Unitarian Universalism in the sky above.

Robinson’s chief literary activity during retirement was returning once again to the history of the Universalist movement in America. He visited libraries holding publications, manuscripts and archives and he wrote several articles on Universalism. In 1970 he published his last book, American Universalism: Its Origins, Organizations and Heritage. Dr. Russell E. Miller, the author of the two volume definitive history of the Universalist denomination, wrote of the volume “Its main theme was ‘the Universalist General Convention, with illustrative supplementary material.’ In addition, part of the work was as much a personal manifesto as a conventional historical study.”

Elmo Arnold Robinson died at Los Alamos, New Mexico on January 17, 1972. To honor his love of ministry his wife established the Elmo A. Robinson Tuition Scholarship at Starr King School for the Ministry. To honor his support of the work of the denomination, the Unitarian Universalist Association’s Legacy Society “was founded in 1988 to honor Elizabeth and Elmo Robinson and others like them who have arranged a gift to the Unitarian Universalist Association in their estate plans or who have made a life income gift.”

Sources

Robinson’s Papers (sermons, correspondence, ministerial reports, and biographical material) and his UUA Ministerial File are at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His major Universalist articles, in addition to those discussed above, include: “Universalism, A Changing Faith,” Journal of the Universalist Historical Society (1960-61); “The Universalist Connections of Thomas Starr King,” Journal of the Universalist Historical Society (1969-70); “The Universalist General Convention from Nascence to Conjugation,” Journal of the Universalist Historical Society (1969-70); and with Alan Seaburg, “The Universalist General Convention: An Historical Table“, Journal of the Universalist Historical Society (1970). For a list of almost all of his writings see “Published articles by Elmo Arnold Robinson as of May 1965,” at the Andover-Harvard Theological Library. For biographical data see Pamela J. Bennett, ed., “Elmo Arnold Robinson: A New England Minister in Indiana, 1914-1917,” Indiana Magazine of History (1972); his monthly church newsletter article, “A Bit of Autobiography,” The Prod to Progress, September 4, 1916; and his “A Universalist Pilgrimage,” Universalist Leader (1958).

Article by Alan Seaburg

Posted December 16, 2016