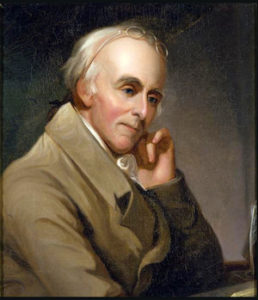

Benjamin Rush (December 24, 1745-April 19, 1813), a signer of the Declaration of Independence, was the most celebrated American physician and the leading social reformer of his time. He was a close friend of both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson and corresponded with many of the prominent figures of the revolutionary generation. Rush’s strong belief in universal salvation helped to promote acceptance of Universalism during its formative period in America.

The fourth of John and Susanna (Hall) Rush’s seven children, Benjamin was raised and spent most of his life in the Philadelphia area. His mother, a Presbyterian, at first supervised her young son’s religious education at home. After the death in 1751 of her Episcopalian husband, she and Benjamin regularly attended the Second Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. There young Rush was greatly influenced by its minister, Gilbert Tennent, a leader in the Great Awakening then sweeping the northeast. Exposure to Calvinist teachings continued during his student years at West Nottingham Academy in Maryland and at the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University). He accepted these doctrines, he later wrote, “without any affection for them.”

After earning an A.B. in 1760 from the College of New Jersey, Rush studied medicine, 1761-66, under Dr. John Redman in Philadelphia. On Redman’s advice, he continued his studies at the University of Edinburgh, where he received an M.D. degree in 1768. He did further training at St. Thomas’s Hospital in London, 1768-69. In Edinburgh he embraced a new explanation of disease, taught by the prominent instructor, Dr. William Cullen. Rejecting the older theory, based upon the balancing of the four humors, Rush believed that the root cause of disease was “irregular convulsive or wrong action,” especially of the blood vessels. The therapy he recommended to restore the circulatory system to normal was blood-letting. Although from the vantage point of two hundred years Rush’s ideas on the origin and treatment of diseases seem poorly founded, in his time they represented advanced thinking and a scientific challenge to traditional medical wisdom.

Returning to America, he joined the faculty of the College of Philadelphia as professor of chemistry. In 1789 he became professor of the theory and practice of medicine. When the college became part of the University of Pennsylvania he was appointed chair of Institutes of Medicine and Clinical Practice, 1791, and chair of Theory and Practice of Medicine, 1796. He was immensely popular with his students; his lectures drew large crowds. His fame drew many students to Philadelphia to study medicine.

In 1776 he married Julia Stockton; the couple had 13 children, nine of whom survived him. Their son James (1786-1869) followed his father into medicine and wrote notable studies of the human voice and of psychology.

Rush was a delegate to the Continental Congress convened in 1775 and a signer of the Declaration of Independence the following year. During the Revolutionary War he served briefly as surgeon-general of the armies of the Middle Department. Finding the army hospitals corruptly and incompetently managed and frustrated that his office did not give him power to reform them, Rush wrote letters of complaint to Congress and to General George Washington. He resigned after Washington accused him of personal disloyalty.

In 1787 Rush and James Wilson led the Pennsylvania convention that ratified the federal constitution; two years later they led a successful campaign to develop a more liberal and effective state constitution. This was Rush’s last involvement in politics, for which he had developed an intense dislike. A decade later President John Adams appointed him Treasurer of the United States Mint, a position he held until his death.

As a physician Rush strove to promote the general health of the citizenry. In 1786 he established the first free dispensary in the country. During the great yellow fever epidemic in Philadelphia in 1793 Rush worked tirelessly and heroically to care for patients and to curb the spread of the disease, at the same time keeping detailed records. In the face of widespread criticism he persisted in promoting drastic purgation and radical blood-letting as a means of treatment. “The more bleeding, the more deaths,” one critic complained, not without cause. Nevertheless Rush was convinced that his treatment was successful and had it applied to himself. His popular and accessible book, An Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever, as It Appeared in the City of Philadelphia, in the Year 1793, 1794, brought him international fame.

Rush made many contributions to medicine that have stood the test of time. He advocated the simplification of diagnosis and treatment of disease. “Let us strip our profession of everything that looks like mystery and imposture,” he wrote. He was an early advocate of preventive medicine. In particular, he pointed out that decayed teeth were a source of systemic disease. He promoted innoculation and vaccination against smallpox.

A pioneer in the study and treatment of mental illness, Rush insisted that the insane had a right to be treated with respect. He protested the inhuman accommodation and treatment of the insane at Pennsylvania Hospital. When he received an inadequate response to his complaints from the hospital’s Board of Managers, Rush took his case to the public at large. In 1792 he was successful in getting state funding for a ward for the insane. He constructed a typology of insanity which is strikingly similar to the modern categorization of mental illness and studied factors—such as heredity, age, marital status, wealth, and climate—that he thought predisposed people to madness. One of many causes of insanity he noted was intense study of “imaginary objects of knowledge” such as “researches into the meaning of certain prophecies in the Old and New Testaments.”

Part of Rush’s treatment of the mentally ill was based upon his idea of the cause of physical disease. One of his prescriptions for a patient was “bleeding . . . strong purges—low diet—kind treatment, and the cold bath.” Anticipating Freudian analysis by a century, Rush also listened to his patients tell him their troubles and was interested in dreams. He recommended occupational therapy for the institutionalized insane. His Medical Inquiries and Observations, Upon the Diseases of the Mind, 1812, a standard reference for seventy years, earned him the title of “the father of American psychiatry.”

Around 1780 Rush read what he described as “Fletcher’s controversy with the Calvinists in favor of the Universality of the atonement.” Soon after he heard Elhanan Winchester preach. According to Rush Winchester’s theology “embraced and reconciled my ancient calvinistical, and my newly adopted [Arminian] principles. From that time on I have never doubted upon the subject of the salvation of all men.” Like Winchester, Rush was what was later termed a Restorationist: “I always admitted . . . future punishment, and of long, long duration.”

Rush frequently attended Winchester’s Universal Baptist church, and he and Winchester became close friends. After Winchester left Philadelphia in 1787, they corresponded. In 1791 Rush wrote Winchester, then in England, “The Universal doctrine prevails more and more in our country, particularly among persons eminent for their piety, in whom it is not a mere speculation but a principle of action in the heart prompting to practical goodness.”

In addition to Winchester, Rush was acquainted with a number of prominent Universalists and Unitarians. When the first general convention of Universalists was held in Philadelphia in 1790, Rush, although not an active participant, played an important part in organizing the convention’s report in its final form. It was then that he first met John Murray, the Universalist leader, and his feminist wife, Judith Sargent Murray, who shared Rush’s interest in dreams. (Judith told him of a dream in which she saw her first husband, “easy and happy,” at the exact reported time of his death in the West Indies, where he had fled to avoid debtor’s prison.) Over the next few years Rush and Murray met several times when Murray visited Philadelphia, once “at the President of the U.S.”—that is, at the home of their mutual friends, John and Abigail Adams. They also corresponded with each other, their letters dealing chiefly with the hypochondrical Murray’s health concerns.

In 1794 when Joseph Priestley came to America, Rush welcomed him at once, and a close friendship developed. Both scientists were interested in religion, believed in universal salvation, and held progressive social views. Later, when Priestley and his wife Mary settled in Northumberland, it was on land purchased with Rush’s help.

When Thomas Jefferson came to Philadelphia as the newly-elected Vice President in 1797, he and Rush renewed a friendship that had begun in the days of the Revolution. For several years they carried on private conversation on religious matters, a subject that Jefferson ordinarily refused to discuss. In 1804 this dialogue, but not their friendship, was terminated because of unreconcilable differences over the nature of Jesus: Rush regarded him as a savior, Jefferson as a man. During 1812 Rush, inspired by a dream, initiated an exchange of letters between Jefferson and Adams. The exchange quickly brought about a reconciliation after a long period of mutual hostility and non-communication.

Rush’s universalism, though for the most part overlooked by his biographers, has been a source of pride to Universalists down through the years—he was the best known national leader to espouse universal salvation. His connection with organized Universalism, however, was only peripheral. He never joined Winchester’s Universal Baptist church, and during the 1790s his interest in all institutional religion waned. With Winchester’s death in 1797, his main link to the Universalist movement was severed.

Although at various times a member of Episcopalian and Presbyterian churches, Rush generally eschewed formal denominational connections. In his later years he confided to John Adams: “I have ventured to transfer the spirit of inquiry (from my profession) to religion, in which, if I have no followers in my opinions (for I hold most of them secretly), I enjoy the satisfaction of living in peace with my own conscience, and, what will surprise you not a little, in peace with all denominations of Christians, for while I refuse to be the slave of any sect, I am a friend of them all. . . . [My own religion] is a compound of the orthodoxy and heterodoxy of most of our Christian churches.”

Rush’s shift from Calvinism to universalism was profoundly influenced by the social changes of the Revolutionary era. He embraced republicanism as an essential part of Christianity. For him a world attuned to God would be one which encouraged people to choose virtue over vice. To create this world it would be necessary to improve the conditions under which all the people lived. At first he envisioned the new American republic as playing the leading role in this transformation. Disillusioned by politics, he concluded that the actualization of the this-worldly millennium was a religious task. Rush’s universalism inspired his work as social reformer. “No particle of benevolence, no wish for the liberty of a slave or the reformation of a criminal will be lost,” he wrote in 1787, “for they all flow from the Author of goodness, who implants no principles of action in man in vain.”

In his time Rush had no peer as a social reformer. Among the many causes he championed—most of them several generations in advance of nearly all other reformers—were prison and judicial reform, abolition of slavery and the death penalty, education of women, conservation of natural resources, proper diet, abstinence from the use of tobacco and strong drink, and the appointment of a “Secretary of Peace” to the federal cabinet.

In 1813 Rush died suddenly after a brief illness. He was buried in the graveyard of Christ’s Church in Philadelphia, the same church whose pastor had christened him 67 years earlier. On learning of his death Jefferson wrote Adams: “Another of our friends of seventy-six is gone, my dear Sir, another of the co-signers of the Independence of our country. And a better man than Rush could not have left us, more benevolent, more learned, of finer genius, or more honest.” Adams, grief-stricken, wrote in reply, “I know of no Character living or dead, who has done more real good in America.”

Sources

The papers of Benjamin Rush are stored at the Ridgway Branch of Philadelphia Library Company, the Pennsylvania. Historical Society, the University of Pennsylvania, the Philadelphia College of Physicians, the New York Academy of Medicine, the New York Historical Society, and the Library of Congress. His correspondence has been published as Lyman H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush, (1951). He was a prolific writer, the author of over 80 published works, including articles and the texts of lectures, addresses, orations, letters, and eulogies. The majority of these were in the field of medicine; others dealt with social issues, education, and government. Among the most important are An Address to the Inhabitants of the British Settlements in America, upon Slave-keeping (1773); Medical Inquiries and Observations, 4 volumes (1789-1815); and Essays, Literary, Moral & Philosophical (1798).

Rush’s own version of his story is preserved in George W. Corner, ed., The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush: His “Travels through Life,” Together with His Commonplace Book for 1789-1813 (1948). Biographies include Nathan G. Goodman, Benjamin Rush: Physician and Citizen (1934) and Carl Binger, Revolutionary Doctor: Benjamin Rush, 1746-1813 (1966). Among many short biographical articles are those by Richard H. Shryock in Dictionary of American Biography (1935), John H. Talbott in A Biographical History of Medicine (1970), and Robert B. Sullivan in American National Biography (1999). Charles A. Howe, “Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Rush: Christian Revolutionaries,” Unitarian Universalist Christian (Fall/Winter, 1989) and Robert H. Abzug, Chaos Crumbling (1994) give accounts of Rush’s religious views. Russell E. Miller, The Larger Hope, volume 1 (1979) and George Hunston Williams, American Universalism: A Bicentennial Historical Essay (1976) portray Rush in a Universalist context. Also important is Donald J. D’Elia, “Benjamin Rush: Philosopher of the American Revolution,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (1974).

Article by Charles A. Howe

Posted April 9, 2002