Charles Spear (May 1, 1803-April 13, 1863) took up the idea of abolishing the death penalty at a time when the idea was widely regarded as a hopelessly impractical, even utopian notion. For years Spear campaigned without stint to change public opinion and the laws, especially in Massachusetts and other New England states, but also throughout the country by means of his newspaper, The Prisoner’s Friend. His long, unremitting and sacrificial efforts had their longed for effect. Application of the death penalty did come to be greatly restricted by law and custom.

Charles and his younger brother, John Murray Spear, born to Universalist parents, were raised from infancy in Boston Universalist churches served by John Murray and Hosea Ballou. After an apprenticeship to a Boston printer, Spear studied for the Universalist ministry under Hosea Ballou 2d in Roxbury, Massachusetts.

Spear preached in many towns and villages as an itinerant for almost two years, and then was the settled pastor of the Universalist Society in Brewster, Massachusetts, for four years, 1828-32. Next, he edited for two years, 1832-34, the Religious Inquirer, a Universalist newspaper in Hartford, Connecticut and preached as a Universalist missionary in the region. He afterward served as settled pastor in Springfield (later Chicopee) and Rockport, Massachusetts. His last pastorate was with the Sixth Universalist Church in Boston which, split by factions, dissolved in 1840, only a year after his coming. For a couple of years afterward Charles worked as a door-to-door missionary and salesman of his self-published devotional volume, Names and Titles of the Lord Jesus Christ.

All this while, as Spear had engaged in the practice of his ministry, he had devoted increasing amounts of time to speaking out in one way or another on behalf of various issues of social reform. Then he read and was inspired by a report of the Marquis de Lafayette’s speech before the Chamber of Deputies in France. “I shall ask,” said Lafayette, “for the abolition of the Penalty of Death until I have the infallibility of human judgment demonstrated to me.”

Spear began himself to write critically of capital punishment in 1830. He and his brother John urged passage of resolutions against capital punishment at the Universalist General Conventions in 1835 and 1836. In 1839 they both were founding members of the New England Non-Resistance Society, an organization led by William Lloyd Garrison and Adin Ballou which renounced violence and all worldly government. In 1841-42 Charles and John Spear organized both the first and second Universalist Anti-Slavery Conventions in Lynn, Massachusetts.

In 1845 Charles Spear was appointed General Agent of the newly founded Massachusetts Society for the Abolition of Capital Punishment. In his Essays on the Punishment of Death, published the previous year, Spear articulated the arguments still used by opponents of capital punishment. He argued that because human life is sacred and capital punishment irremediable, execution is a blasphemous appropriation of divine power. He said a spirit of revenge is unworthy. He considered the horrifying and brutalizing effects upon everyone concerned with an execution—the prisoner, the prisoner’s family, and the spectators.

“Spare the criminal,” Spear pleaded. “The taking of his life will not bring back his victim; it will not prevent others from the commission of crime.”

He declared capital punishment an unjust and arbitrary exercise of power, an instrument not fit for the Republic. Moreover, injustice was multiplied by unequal application of the penalty according to race. Spear contended that the numbers of Negro executions made them a legal instrument of evil whose real purpose was to intimidate and terrorize slaves and thus maintain and enforce slavery.

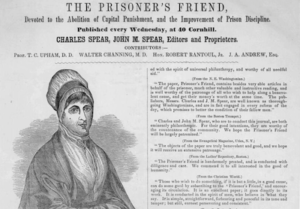

He had earlier said, “I want our prisons to be more like hospitals.” Early in 1845 Spear began to edit and publish the Hangman, soon retitled The Prisoner’s Friend, a journal devoted to transformation of the purpose of prisons from punishment to rehabilitation. From this time Charles gave his life to the advocacy of prison related reforms. He pressed for legislation to end the death penalty. He urged improvement in the living conditions of prisoners. He lobbied for commutation of death sentences. He visited prisoners, helped many parolees, and ran a half-way house for ex-convicts. He became known as himself “the prisoner’s friend.”

Charles was aided by his second wife, Catherine Swan Brown, a reformer known in her own right She and he were partners in their work to abolish the death penalty and to establish the half-way house. The Spears depended for their livelihood on the meager donations of patrons and subscribers to their cause.

In 1862 he enlisted for service as an Army chaplain and was assigned to the Army hospital at St. Elizabeth’s Insane Asylum in Washington, D. C. Although he was soon relieved from duty by the anti-Abolitionist hospital director, Spear set up his own ministry in the hospitals, churches, and military encampments in and around the city. During this period of intensive chaplaincy his health began to fail. Charles Spear died, in April, 1863, of what his wife described as “nervous exhaustion.” He was buried in the King’s Chapel burying ground in Boston.

During the last decade of Spear’s life, his reputation suffered from his being confused with his brother John, who in his middle years turned to spiritualism and also became an outspoken apologist for free love. Some of Charles’s contemporaries in the field of penology considered him, in his passion for reform, a strident, meddling, self-serving amateur. On the other hand William Lloyd Garrison, with whom he worked, wrote that Spear “did the best he could, with very limited means.”

In an address delivered to the Hollis Street Church in 1859, Thomas Starr King recalled, “Ever since I was a child I have known him; and, whenever he visited my father’s house, he came as an incarnate sermon on the iniquity of war, the spirit of charity to all outcasts, and the barbarities of many penalties in our code.” King said Spear had “grown gray in the service of a great principle that belongs to Christianity.”

Sources

The personal journal of Charles Spear for the years 1841-49 is at the Boston Public Library. Documents containing information about his work in Washington, D.C. at the end of his life are in An Act Granting a Pension to Catharine S. B. Spear at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. Spear’s most significant published works are the periodical The Prisoner’s Friend (also known as The Hangman), 1845-1857, Essays on Imprisonment for Debt (1833), Essays on the Punishment of Death (1844), and Voices from Prison (1847). The latter is a collection of poetry and verse written by prisoners, published as an effort to humanize prisoners to the outside world, and to show that prisoners have an unusual opportunity for spiritual inspiration. Spear wrote many other tracts, essays, circulars, and reports.

No thorough biography of Charles Spear has been published; however, much of his life is recounted in John Buescher’s biography of his brother, The Remarkable Life of John Murray Spear: Agitator for the Spirit Land (2006). Among short biographical accounts are Thomas Starr King’s An Address in Behalf of Rev. Charles Spear, Delivered in the Hollis Street Church (1859), an entry by Blake McKelvey in the Dictionary of American Biography, and an entry, possibly by George Ripley, in Appleton’s Cyclopedia of American Biography. Charles’s career as an activist against the death penalty is examined briefly in Louis P. Masur, Rites of Execution: Capital Punishment and the Transformation of American Culture, 1776-1865 (1989) and in Alan Rogers, “‘Under Sentence of Death’: The Movement to Abolish Capital Punishment in Massachusetts, 1835-1849,” The New England Quarterly (1993). There is an article on the activist career of Catharine Swan Brown Spear in the biographical encyclopedia, A Woman of the Century (1893).

Article by John Buescher