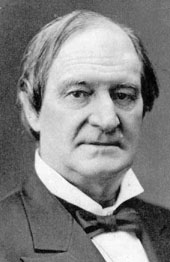

Alphonso Taft (November 5, 1810-May 21, 1891), one of Cincinnati’s most prominent citizens and among Ohio’s most highly regarded 19th-century attorneys and jurists, wrote an influential dissent on Ohio’s “Bible in the Schools Case.” He was the progenitor of a family politically influential in both Ohio and Washington. During his more than forty years as a member of First Congregational Church (Unitarian) his devotion and service to the congregation made him a pillar of the church.

Alphonso was born in Townshend, Vermont, son of Sylvia Howard and Peter Rawson Taft, a farmer, lawyer, and local judge. The Tafts’ only child received the best available public school education, and his parents encouraged him as he worked to pay his way through Amherst Academy and Yale College by teaching high school. He graduated from Yale in 1833, third out of 90. He taught high school again, and tutored college students, in order to attend Yale Law School. He graduated in 1838. Following an exploratory trip to the West in 1838-39, he moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he apprenticed at a law office. Admitted to the Ohio bar in 1840, he set up practice. His legal success led to service on the Cincinnati City Council for five years during the 1840s. He effectively championed annexation of suburbs to further strengthen the city’s commercial base.

In 1841 Taft married Fanny Phelps, the daughter of family friends in Vermont. They had five children; two survived early childhood. After Fanny died in 1852, Alphonso’s parents came to live with him and his two sons. In 1853 Alphonso married Louise Torrey, daughter of prominent Milbury, Massachusetts parents. They had four sons and a daughter. The first son died in childhood; the second, born in 1857, was William Howard Taft, later the twenty-fifth president of the United States. All of Alphonso Taft’s sons graduated from Yale.

Although Taft had been brought up a Baptist, he had no religious affiliation when he first settled in Cincinnati. He attended Baptist services occasionally with Fanny and heard some of Lyman Beecher’s sermons at 2nd Presbyterian Church. In the mid-1840s he discovered First Congregational Church (Unitarian), whose services and members he found congenial. He joined in 1847 or 1848 and Fanny became a member shortly thereafter. Taft’s second wife, Louise, who had been brought up as Unitarian, became an active member in the Cincinnati church. Alphonso was many times a trustee and, more than once, board chairman. The church split and lost half its membership during the ministry, 1856-1862, of the theological and social radical Moncure Conway. Charles Wendte, minister of First Congregational Church, 1875-1882, said of Taft that “In religion he was a radical Unitarian, and had upheld Mr. Conway in the church dispute which the latter’s advanced views had entailed.” His steadfast support of Conway was perhaps the most public statement Taft ever made regarding his religious position.

Taft was active in Whig politics until the party dissolved because of the slavery issue. In 1855 he was a founder the national Republican Party and its Ohio affiliate. He remained active in Ohio Republican politics for the next 34 years.

In 1865 Taft was appointed to fill an unexpired term as a Judge of the Superior Court of Cincinnati (part of the Ohio State Court System). He was subsequently elected to two terms. A trustee of two railroads, he lobbied vigorously for Cincinnati to construct a new railroad to the South. As a judge he approved the sale of bonds by the city for this purpose. The Cincinnati Southern Railway became the country’s only profitable municipal railroad. Taft resigned from the bench in 1872 to join his two grown sons in private practice. He was elected the first president of the Cincinnati Bar Association in 1872, served as a trustee of Cincinnati College, and taught at Cincinnati Law School.

One of Taft’s opinions as a judge, against Bible-reading in public schools, remains meaningful today. Several other local Unitarians, including members of his church, were actors in the drama that led to a landmark decision about church and state.

Since 1829, when the public school system in Cincinnati was founded, daily reading of the King James Bible and the singing of Protestant hymns had been the custom in each schoolroom. This went unchallenged until Archbishop John Baptist Purcell objected on behalf of the thousands of Catholic children in the system. By the late 1860s Archbishop Purcell’s protest had been seconded by Rabbis Isaac M. Wise and Max Lilienthal on behalf of Cincinnati’s substantial population of Reform Jews. The Board of Education was divided over proposals to end the practice. The only two clergymen on the Board were Unitarian ministers, the ultra-liberal Thomas Vickers of First Congregational Church and conservative Amory Dwight Mayo of the Church of the Redeemer. The former was the leading spokesman for the Unitarians and for Cincinnati’s large number of freethinkers; and the latter was equally prominent as an advocate for the pro Bible-reading forces. It is a supreme irony that the leading spokesmen on this contentious issue, in one of the most religiously heterogeneous cities in the country, were two Unitarian ministers. Their combined congregations made up less than two-tenths of one percent of the city’s population!

In 1869 the Board of Education voted in favor of excluding Bible-reading from the public schools. Two days after, a large group of prominent citizens successfully petitioned Judge Bellamy Storer, of the Superior Court of Cincinnati, to issue a temporary injunction preventing the Board from implementing its decision. A few weeks later, a trial was held before a three-judge panel of the Superior Court to decide whether the injunction should be vacated or made permanent. The entire controversy and the ensuing trial were covered intensively by the nation’s leading newspapers. Two of the three judges were leading conservative Protestant laymen. The third was Alphonso Taft. Among the anti-Bible-reading attorneys was former judge George Hoadly, Cincinnati’s leading corporate attorney, a future governor of Ohio, and a longtime member of First Congregational Church. The outcome of the trial was a permanent injunction on the Board of Education allowing continued Bible-reading in the schools.

Taft wrote a significant dissenting opinion on the Bible in the Schools Case. “I can not doubt,” he wrote, “that the use of the Bible with the appropriate singing, provided for by the old rule, and as practiced under it, was and is sectarian. It is Protestant worship. And its use is a symbol of Protestant supremacy in the schools, and as such offensive to Catholics and to Jews. They have a constitutional right to object to it, as a legal preference given by the state to the Protestant sects, which is forbidden by the Constitution. . . . When the Board of Education, therefore, which represents the civil power of the State in the schools, finds objection made to the use of the Protestant Bible and Protestant singing of Protestant hymns, on conscientious grounds, and concludes to dispense with the practice in the schools, it is no just ground to charge on the Board hostility to the Bible, or to the Protestant religion, or to religion in general. The Bible is not banished, nor is religion degraded or abused. The Board has simply aimed to free the common schools from any just conscientious objections, by confining them to secular instruction, and moral and intellectual training.”

Although Taft’s eloquent dissent was of no immediate avail, the controversy continued until the Ohio Supreme Court reversed the ruling in 1873. Its unanimous decision upheld Taft’s dissent. This remains an important precedent in Establishment of Religion law.

In 1876 President Grant, in an effort to put a clean face at the head of a corruption-plagued department, appointed Taft Secretary of War. Mercifully, later that year he made Taft Attorney General, in which capacity he served with distinction until the end of the administration. He was the leading contender for the Republican Party nomination for Governor in 1875 and 1879. He lost each time at the convention, largely because his opinion on the Bible in the Schools Case was intensely disliked by the evangelical Protestants. In 1882 he was appointed ambassador to the Austro-Hungarian Empire and, in 1884, ambassador to Russia. He retired in 1885 due to illness, and resumed private practice. Five years later, for health reasons, he retired to San Diego, California, where he died.

The first 16 reels of the William Howard Taft Papers, Series 1, in the Library of Congress are devoted to family correspondence during the lifetime of his father, Alphonso Taft. His and Louise Taft’s letters to and from her sister, Delia Torrey, are particularly useful. The records of First Unitarian Church of Cincinnati are in the Library of the Cincinnati Historical Society. Biographies include William Howard Taft, Alphonso Taft Hall Dedication Address (1925); Lewis A. Leonard, Life of Alphonso Taft (1920); and Ishbel Ross, An American Family: The Tafts—1678 to 1964 (1964). There is an entry in American National Biography (1999). For more information on the Bible inthe Schools Case see Harold M. Helfman, “The ‘Cincinnati Bible War,’ 1869-1870,” Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly (October, 1951) and Robert Michaelson, “Common School, Common Religion? A Case Study in Church-State Relations, Cincinnati, 1869-1870,” Church History (June, 1969). The Bible in the Public Schools (1870, new edition 1967) includes all the arguments, the opinions of the Superior Court judges, and the opinion on appeal of the Ohio Supreme Court. See also Charles William Wendte, The Wider Fellowship: Memories, Friendships, and Endeavors For Religious Unity, 1844-1927 (1927).

Article by Walter Herz

Posted January 27, 2007