Harry Toulmin (April 7, 1766-November 11, 1823), a Unitarian minister in Britain, emigrated across the Atlantic in search of religious freedom and tolerance. In America he had careers in education, government, and law. As a judge in the turbulent Mississippi Territory, he was able to use his influence to prevent warfare with the Spanish. He made the first record of law codes in three states.

Born in Taunton, England, Harry was the son of noted theologian and Dissenting minister Joshua Toulmin and Jane Smith Toulmin. Harry was educated first in his mother’s bookstore and then in the intellectually stimulating company of his father and his father’s colleagues, including Joseph Priestley and Theophilus Lindsey, where he heard open and vigorous discussions of Socinian beliefs and learned to value logic and reason. He attended Hoxton Academy for a time, and prepared for ministry under Rev. William Hawes of Bolton and Dr. Thomas Barnes in Manchester.

In 1786 Toulmin began preaching. He served two congregations of Protestant Dissenters in Lancashire, near Manchester: Monton (Eccles), 1786-88, and Chowbent (Atherton), 1787-93. His radical Unitarian preaching and writing drew a large number of followers, said to have numbered nearly a thousand. Lindsey described the Chowbent congregation under Toulmin as “one of the largest and most enlightened.” Around 1787 Toulmin married Ann Tremlett. The Toulmins had nine children, four of whom died young.

Many of Toulmin’s mentors and colleagues supported the French Revolution. Their praise for the revolution and espousal of such ideals as independence and liberty were, however, subject to suppression by the British government and condemnation by xenophobic mobs. In 1791, Priestley’s laboratory, home, and meeting house in Birmingham were attacked and destroyed. An effigy of Thomas Paine was burned at Joshua Toulmin’s door. Harry also attracted the attention of anti-dissenting forces. He was threatened with injury, an informer reported his conversation to the authorities, and a mob surrounded his house while he was away. In the latter instance, when he heard of his family’s peril, he raced home and used diplomacy, daring, and calm to disperse the crowd.

There was also trouble at the Chowbent church. “Mr. H. Toulmin tells me,” wrote Lindsey in 1793, “that in the midst of the service, a recruiting party (who with their attendants had been parading at 11 and 12 o’clock on the Saturday night with torches, and huzzaing and knocking at the houses of Dissenters) passed by the Chapel with drums and fifes and shoutings when opposite to it, crying “Down with the Rump” so as to hinder him from going on till they had done; and after the service a party of the rabble wanted to lay hold on him to put a cockade in his hat, as they had forced many of the congregation, but being apprized of their design, he escaped out by another door.”

In 1792 Toulmin anonymously published his Thoughts on Emigration, with sections titled “reasons for thinking of a removal, the discouragements attending it, the most eligible country for removing to, and the steps to be taken by those who have it in contemplation.” Among ten “reasons for thinking of a removal” he mentioned the high tax burden, the inability to elect lawmakers, the impossibility of obtaining justice from a legal system created by and for the privileged, status as subject rather than citizen, and the corruption of the ruling classes. He also noted a desire for independence, a hope to provide for and educate one’s children, and “an attachment to religious equality and to religious harmony.” America was, according to him, a land where “you are not compelled to pay towards the propagation of a faith which you do not believe . . . you are not threatened with fines or imprisonment for any articles of your creed . . . You may calmly inquire after the truth.” He pictured America as “a fine field for the diffusion of religious knowledge. The minds of the people are not shackled by articles and creeds. Their senses are not captivated by the pomp of superstition, nor their judgments fettered by the trammels of authority. In America, to contend for the faith, is not to contend for power: to publish the truth, is not to preach sedition.”

By 1793 Toulmin’s congregation had collected enough to send him and his family to America, to find land where members of the congregation might all settle. In the event only his brothers followed him to America. He later bought land in Kentucky for another person, Ebenezer Tipping, who never came over to claim it. British anti-emigration propaganda and disruptions in sea traffic resulting from the Wars of the French Revolution, including an American embargo on British shipping from March 1794 until June 1795, may have inhibited further emigration from Chowbent.

Traveling with his wife and children, and equipped with letters of introduction from Priestley to Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, Toulmin sailed to Norfolk, Virginia. During the two-month voyage, he kept a journal (published as The Western Country in 1793; Reports on Kentucky and Virginia, 1948). In letters sent back to England for publication in the Monthly Magazine, he wrote of the cost of everyday materials, what it would cost to live in this place or that, the quality of the water and food, and the nature and expense of transportation. In short, he explained everything an immigrant would need to know, including what foods to bring on the voyage, and what to leave behind.

Acquaintance with Jefferson and Madison led to Toulmin serving as the second president of Transylvania Seminary (later University) in Lexington, Kentucky, 1794-96. His short tenure was troubled. Conflict between the Presbyterians who had begun the seminary and the more liberal board members who had elected Toulmin resulted in a legislative amendment that required a unanimous vote of the board to reelect the president. In his letter of resignation Toulmin predicted that the new requirement would “forbid the approach of every man of spirit and independence.”

While serving as the president of Transylvania Seminary, Toulmin became acquainted with James Garrard, a Baptist minister and a member of the Transylvania board. When Garrard was elected Governor of Kentucky in 1796, he appointed Toulmin Secretary of State. Toulmin signed the 1798-99 Kentucky Resolutions, drafted by Jefferson, protesting the Alien and Sedition acts passed by Congress in 1798. Toulmin believed these acts represented unwarranted government intrusion into free thought, free association, and free speech. During his two terms as Secretary of State he compiled, for the first time, the laws of the new state. By doing this he hoped to make the legal system accessible to all citizens.

Although Toulmin no longer functioned as a member of the clergy, he still actively taught his faith. He distributed his father’s and Lindsey’s tracts. He made such an impression upon Garrard, that Garrard was asked to leave his pulpit. Another Baptist minister, Augustine Eastin, who adopted Toulmin’s Unitarian views, was expelled, together with his church, from the Elkhorn Baptist Association.

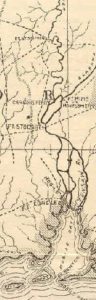

In 1804 President Jefferson appointed Toulmin superior court judge for the Tombigbee district of the Mississippi Territory (now southwest Alabama). The only civil government representative in a vast, sparsely settled wilderness region, he acted as judge, diplomat, postmaster, and road-surveyor. He also performed weddings and funerals and practiced medicine. During his administration two great waves of migration increased the population of his district more than tenfold. He strove to bring order, stability, and the rule of law to a frontier outpost threatened from without by foreign powers and from within by unruly settlers and warring Indian tribes.

The settlers of his jurisdiction objected to Spanish control of Mobile Bay, which isolated them from New Orleans and the Mississippi River. In 1805 Toulmin appealed in their behalf to Congress and to the Spanish for relief from Spanish tariffs, embargoes, and confiscations. Having failed at this, he worried that settlers might be incited to attack Mobile. In 1807 Toulmin arrested Aaron Burr, rumored head of a conspiracy to create a new independent state in the southwest. In 1810 a group of adventurers organized the “Mobile Society” to liberate Mobile and Pensacola. Toulmin advised a grand jury that such unauthorized invasions were illegal and not in the interest of the United States or of good government. Although personally favoring annexation of West Florida by the United States government, he declared that so long as West Florida was a foreign state he would uphold the laws protecting it as such. Shortly afterward, he stood by his principles and sacrificed some of his popularity by arresting three would-be liberators. Those he had arrested attempted unsuccessfully to have Toulmin impeached by Congress.

Although Toulmin succeeded in keeping relations with the Spanish sufficiently amicable that the periodic filibustering crises did not lead to warfare, during the Creek Wars of 1811-13 (between two opposing nations of Creek Indians, and drawing in the British and the American settlers as well) he was less successful in preventing violence. He tried to impartially investigate the wrongs committed on all sides, but was unable to reconcile the warring parties.

Following the eventual American annexation of West Florida, the new state of Alabama was created. In 1819 Toulmin took part in the statehood convention and was subsequently elected to the new Alabama legislature. He was the first person to codify the laws of Mississippi and Alabama.

Toulmin had a plantation near Fort Stoddard, Alabama on which he grew cotton. Although he had been appalled by slavery when he first encountered it upon his arrival in Virginia, he later came to own slaves. In his will he made provision for the emancipation of one of his slaves as “he is fit for freedom which few negroes are.” He likely shared the views of his slaveholding friend, Kentucky Governor Garrard, who believed in the eventual abolition of slavery yet was in the interim a slaveholder.

In 1812, shortly after the death of his wife Ann, Toulmin married Martha Johnson. They had one child. Toulmin died on his plantation in 1823.

Sources

Toulmin letters are at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; the State Department, Washington, D.C.; and the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, Mississippi. Letters to and about Toulmin are printed in “Letters from Theophilus Lindsey to Harry Toulmin,” Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society (October 1974) and “Letter of Theophilus Lindsey to Russell Scott, 26 March, 1793,” Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society (1947). Aside from the works mentioned above, Toulmin’s publications include A Short View of the Life, Sentiments, and Character of John Mort (1788), A Description of Kentucky, in North America: to Which Are Prefixed Miscellaneous Observations Respecting the United States (1792), A Collection of All the Public and Permanent Acts of the General Assembly of Kentucky (1802), A Review of the Criminal Law of the Commonwealth of Kentucky (1804, with James Blair), The American Attorney’s Pocket Book (1806), The Magistrates’ Assistant (1807), The Statutes of the Mississippi Territory (1807), A Petition from the Citizens of Clarke, Monroe, Washington, Mobile, and Baldwin in the Alabama Territory (1817), and A Digest of the Laws of the State of Alabama (1823).

There are short biographies of Toulmin in Willard Rouse Jillson, A Transylvanian Trilogy: The Story of the Writing of Harry Toulmin’s 1792 “History of Kentucky,” Combined with a Brief Sketch of His Life and a New Bibliography (1932); American National Biography; and Dictionary of American Biography. An importance source is Leland L. Lengel’s Duke University thesis, “Keeper of the Peace: Harry Toulmin in the West Florida Controversy, 1805-1813” (1962). Information on Toulmin’s life can be also gathered from Albert J. Pickett, History of Alabama, vol. 2 (1851); Isaac J. Cox, The West Florida Controversy, 1798-1813 (1918); Niels H. Sonne, Liberal Kentucky, 1780-1828 (1939, repr. 1968); H. E. Everman, Governor James Garrard (1981); and Willard C. Frank, Jr., “‘I Shall Never be Intimidated’, Harry Toulmin and William Christie in Virginia 1793-1801,” Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society (April 1987).

Article by Clara Keyes

Posted August 24, 2002