Edward Mott Woolley (October 31, 1803-May 4, 1853) was an itinerant, circuit-riding Universalist minister in New York and Michigan. He was the father of Lucia Fidelia Woolley Gillette, one of the first women Universalist ministers and the grandfather of Clarence Mott Woolley, a prominent twentieth-century industrialist and a benefactor and trustee of St. Lawrence University.

Edward Mott Woolley’s parents, Elizabeth Mott and Edward Woolley, were tenant farmers who worked land near Dover in Dutchess County, New York. Devout Quakers, they had seven children with Edward being the youngest. From age 6 to 16 he walked to a local school. He wanted to learn Latin and study the law but family reversals led his parents to apprentice him to his older brother Gideon for a term of four years. He worked in his brother’s shoe and leather finishing business in nearby Pleasant Valley, New York and lived as one of his brother’s family. He read Robert Burns and Seneca by candlelight but there was little time for studies or attending lyceum programs. He attended the Presbyterian church with brother Gideon’s family and when he was 18—after the excitement of a revival—he became a Presbyterian. But this conversion soon faded. When Gideon moved his family and business to Poughkeepsie, a few miles east of Pleasant Valley, Edward went along. Poughkeepsie, on the Hudson River, was flourishing and Edward enjoyed the ferment, finding interesting new companions. Having completed three years of his apprenticeship he decided to join with two of these new friends and go on the road as itinerant teachers. One of these new friends was a Universalist from Philadelphia, the first Universalist Edward had known.

When he was twenty, Edward Mott Woolley moved to Nelson in Madison County, New York where his brother James Titus already lived. His sister Eunice was in nearby Cazenovia. Edward worked as a shoemaker, lived with brother James, and once again joined the local Presbyerian church. When he could he studied history, natural philosophy, and grammar on his own. For one winter he returned east to his parents home so he could attend formal classes. As he studied, his thoughts turned increasingly to the bigger questions raised by religion.

On Christmas day 1825 Edward Mott Woolley married his Nelson neighbor, Laura Smith. She was described as “fond of social parties,” in feeble health, of “great personal beauty,” and of superior education. They moved into a new house across the road from the tannery where he worked. Their first child, Lucia Fidelia was born two years later.

Things were prosperous in central New York; the Erie Canal opened in 1825 and after only a few years of shoe making, Woolley—and his brother-in-law James Benedict—were able to buy 31-acres in Cazenovia, New York, just four mile west of Nelson. It was a place where his parents could retire. In 1826, aged 65 and 67, his parents settled into a new house on the property in Cazenovia.

In 1826-7 the town of Nelson built a union meeting house and the Universalist preacher Nathaniel Stacy was engaged to preach once a month for a year. During that year, Woolley slowly changed his opinion of Universalism from deep aversion to full agreement. Nathaniel Stacy recalled in his memoirs that, “Among those who seemed to take deep interest was a young man by the name of E. M. Woolley, a resident of the village,—a young man of superior talents, but a zealous opposer of the doctrine; and, as I desired, he was very eager to oppose it, and seize every opportunity to battle with me.”

Woolley and his wife, along with daughter Lucia Fidelia, moved in with his parents on the Cazenovia farm for a few years. Woolley set up a shoe work-shop on the farm so he could work at home and a son Edward Jackson was born. But it wasn’t long before they moved back to Nelson where he met Universalist preacher John Freeman, who was preaching at the Court house in Morrisville. Freeman and Woolley would become fast friends.

In the winter of 1831 the family moved to Munnsville, where Woolley opened his own shoe and leather shop. Universalist circuit-riders John Freeman, David Biddlecorn, and Stephen Rensselaer Smith all visited the area, preaching at a nearby school house.

Early Universalists often used folk-tale or tall-tale story elements in sermons and talks. Universalist meetings at that time were all male affairs but according to one story, after Mrs. Woolley attended a Universalist service, the ice was broken and other women followed. Stories about debates and confrontations with ministers from other sects were also popular as were stories of deathbed conversions, epiphanies, visions, and signs in dreams. In 1836 Woolley held a two day disputation with a Methodist minister in Poolville. If he was invited to give a prayer at a funeral he was not above expanding it into a short sermon featuring the message of Universal salvation. It’s said that halfway through a sermon in Siloam, in the winter of 1833, the preacher, John Freeman said, “Mister Woolley will you finish the sermon?” All eyes were on Woolley. He rose, went to the table, and successfully delivered his first sermon. Another Woolley story is that when Stephen Rensselaer Smith asked Woolley to replace him as the preacher in Clinton, New York, Woolley refused saying, “I know too much to try to follow you as a preacher.”

Instead of going to Clinton, Woolley was increasingly called on to substitute for ailing John Freeman in Hamilton. When Freeman died in October 1834 Woolley was called to replace him so the family packed and moved to Hamilton. On alternate Sundays he preached in Lebanon. The Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate said “Br. Woolley was in feeble health but blessed with an active mind.” Since the Hamilton Universalist church was too small, he was ordained in the Presbyterian Church on August 21, 1834. Taking part in the ordination were B. T. Wheeler, Stephen Rensselaer Smith, Br. O. Roberts, Br. D. Biddlecom, and Br. A. K Marsh.

In 1837 Woolley preached funeral sermons in Pompey and Manlius; participated in the New York Central Association of Universalists convention including holding a position on the fellowship and ordination committee, and he participated in the ordination of W. M. Delong. In May the economy started to falter and a seven year depression—the Panic of 1837—set in. Woolley lost money he had loaned to a friend.

His father was dead and his mother was alone at Cazenovia so the family moved back to the farm in Cazenovia. His services were split among churches at Oran and Howlett Hill as he took care of his mother. In fall 1838 he sold the farm to pay off debts. His mother went to stay with another son, Alfred. Woolley’s health was always poor—he had bronchitis and lung problems—making farm work and constant ministerial travel oppressive but in February he returned to preaching in Lebanon with occasional trips to North Norwich.

He was able to attend the State Convention of Universalists in Fort Plain, New York. Emaciated and weak when he returned from the convention, Stephen Rensselaer Smith urged him to go to Saratoga, New York for rest. For two weeks he grew worse at Saratoga but then he started to recover from his “bronchial consumption.” In 1840 his mother died. When he attended the 1840 United States Convention of Universalists in Auburn, New York he saw and heard Hosea Ballou for the first time.

The area of western New York state where Woolley preached is often called the Burned-Over District because it was such a hotbed of religious movements and revivals during the early years of the ninteenth-century. In an 1840 sermon Woolley separated himself from the excesses of the Second Great Awakening saying “In this age of excitement and contention, judgment and reason are seldom allowed to speak. Passion—loud, boisterous passion—is the propelling power by which the car of religious fanaticism and folly is pushed along. The sober morals and wholesome precepts of Christ and his apostles are, in a great degree, discarded, and a new order of things introduced.”

In 1841 Woolley was the moderator of the Madison County Universalist Convention, he preached in Morrisville and Marshall, and performed a marriage in Lebanon. He was called to the Universalist society in Bridgewater with the provision that he would preach quarter time at North Norwich. In June he was guest preaching in Clinton, New York. The next year he took on duties in Cedarville, Herkimer County and he became friends with Universalist publisher A. B. Grosh, editor of the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate in Utica, New York.

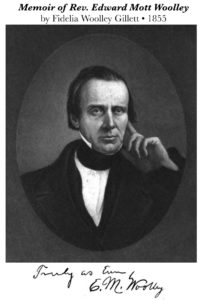

His physician prescribed a change of climate so in the summer of 1843 he visited Michigan, Illinois, and the Wisconsin Territory, preaching along the way. In Chicago he had a daguerreotype (picture at top of this article) taken. Coming home he stopped at Niagara Falls. The Michigan Territory had gained statehood six years earlier in 1837, western emigration had increased rapidly after the war of 1812. Overland travel was hard—few rivers were bridged—but steam powered passenger boats on the Great Lakes made lake travel easy and comfortable. The best land route from Buffalo to Detroit was across what was then called Upper Canada. In Michigan the new emigrants were called Yankee-Yorkers; emigrants from upstate New York with family roots going back to Massachusetts and Connecticut.

In 1845 Woolley participated in the Universalist Convention of New York State where he gave a prayer and served as assistant clerk. T. J. Sawyer was chosen as moderator. That same year Dolphus Skinner in Utica, New York recommended Woolley to the Universalists in Pontiac, Michigan who were looking for a pastor. He accepted the call, leaving his family in Bridgewater and traveling west. He was in the pulpit on the first Sunday in October, 1845. Universalism in Michigan—at that time—consisted of two dozen small societies organized into a Central Association. Few Universalist societies had buildings so they met in schools, meeting halls, and union church buildings. Most were led by lay members who arranged services around quarter or half-time circuit-riding ministers. A small Universalist society in nearby Wayne, Michigan was led by David Ravlin, a lay preacher. Woolley worked with Ravlin to convert and recruit Chauncy Washington Knickerbacker to the Universalist ministry.

Michigan did have its own Universalist newspaper, The Primitive Expounder which was published in Ann Arbor, 1843-48. It contained a mix of Fourierism, spiritualism, phrenology, and Universalist articles and news. Michigan also had its own Universalist utopian community, Alphadelphia. It was located near Kalamazoo, Michigan which—at the time—was the western end of the Michigan Central Railroad. For one year, 1846, The Primitive Expounder was printed at the Alphadelphia commune.

Leaving Detroit in March of 1847 Woolley crossed the Detroit River on the ice and journeyed back east in lumber wagons through Upper Canada. After crossing over to Buffalo he walked home to his wife and children in Bridgewater, New York. In May the family headed west with many of their possessions, going by wagon to Utica and then west by boats on the Erie Canal to Buffalo. After a visit with Stephen Rensselaer Smith they caught a lake steamer for Detroit. One daughter and one son stayed behind in New York for another year before joining the family in Michigan.

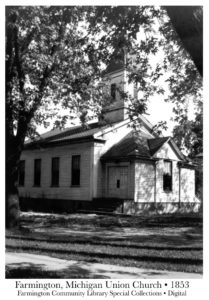

The Woolley’s settled in a new house on a small farm about two miles from Birmingham, Michigan. He continued preaching on alternate Sundays in Pontiac and Birmingham. Both towns were stops on the new Detroit and Pontiac Railroad. He also preached occasionally in nearby Farmington, Michigan in a room over George Wright’s wagon-shop, and afterwards in a room which Sergius Lyon had fitted up to be used as a school-room and place of worship. Many of the original settlers in Farmington had been Quakers but their numbers were thinning. In 1849 Woolley was preaching in Farmington, Franklin, Livonia, and Waterford, Michigan. There were few meeting houses until Union churches were built in Livonia and Farmington, Michigan. Despite his poor health, Woolley preached 25 sermons in one month and participated in a marathon religious debate with Rev. C. C. Foot, a Unionist preacher. That debate lasted two and a half days. There was also Universalist Society in Avon township, a few miles northeast of the Woolley home; the group had organized in 1838 but didn’t build a church building until after the Civil War.

In June of 1849, his daughter Eunice married Mr. H. Belding, of Troy, Michigan. The following year he officiated when daughter Lucia Fidelia married Hartson Gillette. Fidelia and Hartson settled nearby. In December 1852, his third daughter Laura Ann Woolley married Charles Farmer. His youngest daughter Esther Almira Woolley, never married: she settled in Avon (later Rochester), Michigan where she was very active in the Universalist Society and Church.

At some point the Woolley’s separated and his wife Laura returned to Nelson, New York to live with her parents. Their youngest daughter, Esther Almira is listed on the 1850 census as living with her mother and attending school in Nelson. According to an 1851 Michigan divorce petition Woolley’s wife went back east in June 1848, returning two years later. The petition claims she was jealous and violent for most of their married years, that she beat the children, and that she once attacked Woolley with an iron shovel, threatening to “split his brains out.”

According to the Memoir of Rev. Edward Mott Woolley (1855) written by his daughter Fidelia Woolley Gillette, he remarried after the divorce. Fidelia didn’t mention the friction between her parents or their divorce in her biography but in the book’s preface, Rev. A. B. Grosh says that Fidelia:

“. . . omitted a long train of domestic grievances, ending in a divorce from the mother of his children,—not for any criminality other than her unkindness and desertion,—in all of which Mr. Woolley was sustained, and his course fully approved, by all the children. This was followed, after a proper interval (at the very close of his life), by a second marriage, which his family generally approved.”

Woolley continued to suffer from breathing problems and bronchial disease, probably Tuberculosis. Death and illness was as common in Michigan as it had been in New York state. He was often called to pray by the bedside of the dying, to counsel the grieving, or to preside at burials. In the summer of 1850 both a son and a daughter were ill. “They tell me my children are sick enough to die, and yet I cannot understand it,” he said, “I cannot make myself see the cold, quiet face, the dim eye, the compressed lip, the silent feet, and the lifeless form . . . And I thank God I cannot.”

His brother James Titus Woolley died in 1851 in Homer, Michigan. Edward Mott Woolley took to his own sick bed in December 1852 and died five-months later. He was buried in Birmingham, Michigan. He had settled his affairs before dying; three of his daughters had recently married; the fourth, eleven-year-old Esther Almira, was in school and living with her mother and her mother’s family in Nelson, New York; and his twelve-year-old son, Smith Rensselaer Woolley, had been placed with a local farm family.

In the spring of 1853 the Universalists in Farmington started building their own place of worship. By summer they had a new Union Church on Warner street stretching from Thomas to Third. It was open to all and it shared a bell that was hung in the nearby Methodist church steeple. A bit of Yankee New England on the western frontier it was still in use in 2015. The Pontiac church where Woolley had preached closed and the property was later sold by Universalist minister Chauncy Washington Knickerbacker. In May 1866, Knickerbacker, now the standing clerk of the Michigan Universalist Convention, moved Edward Mott Woolley’s remains to Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit, Michigan.

Sources

The sole biography is by his daughter Fidelia Woolley Gillett, Memoir of Rev. Edward Mott Woolley (1855). It contains some poems and extracts from his letters and sermons. A 20-page condensation can be found in the Universalist Quarterly and General Review (Oct 1855). Woolley is mentioned in two books by Stephen Rensselaer Smith; Historical Sketches and Incidents, Illustrative of the Establishment and Progress of Universalism in the State of New York (1843); and Memoir of the Late John Freeman (1835). The second Smith book includes a poem by Woolley. Also see Nathaniel Stacy, Memoirs of the Life of Nathaniel Stacy, Preacher of the Gospel of Universal Grace (1850), which covers early Universalist activities in the old Northwest Territory. A rich source of of Universalist activities in Michigan is Gwen Foss, Diaries of the Reverend Chauncy Washington Knickerbacker, Universalist Minister: 1843-1888 (2007)

Short mentions of Woolley are also found in meeting announcements, participant lists, and Universalist convention and association reports in the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate, Universalist Union, Religious Inquirer and Gospel Anchor, Western Luminary, Universalist Expounder, and Universalist Convention year books. Some information can be gleaned from local histories such as, Charles R. Tuttle, General History of the State of Michigan (1873); L. H. Everts & Co., History of Oakland County, Michigan (1877); and Kace Publishing Co. Illustrated Atlas of Oakland County (1896). On-line sources include SeekingMichigan.org, Newspapers.com, Ancestry.com, and the University of Michigan’s Making of America digital archives.

Article by Jim Nugent

Posted January 27, 2015